Contemporary Western society is marked by a loss of the sense of place, and its intellectual traditions, far from controlling this loss, have encouraged it. The still persistent concerns which we have for the places about which we care are therefore inadequately represented in our formal political discourse; with the result that, being neither recognized nor properly criticized, they build up frustrations which break out in disruptive aspirations and claims which are less natural and less reasonable. Humanity is not fitted to live in placeless communities, the creations of pure human will unmediated through natural circumstance, the communities which are offered to us by the liberal tradition of political theory.

– Oliver O’Donovan, “The Loss of a Sense of Place,” (Bonds of Imperfection, 1989)

Part I: Here we are…

I begin with a passage for this audience, taken from a lecture given in 1986 at Queen’s University, Belfast, by Anglican theologian and ethicist Oliver O’Donovan, simply as an outside-the-architecture-guild confirmation of a baseline premise for what follows, viz. the miserable state of the built environment the modern west has been making (and exporting) since the end of World War II.

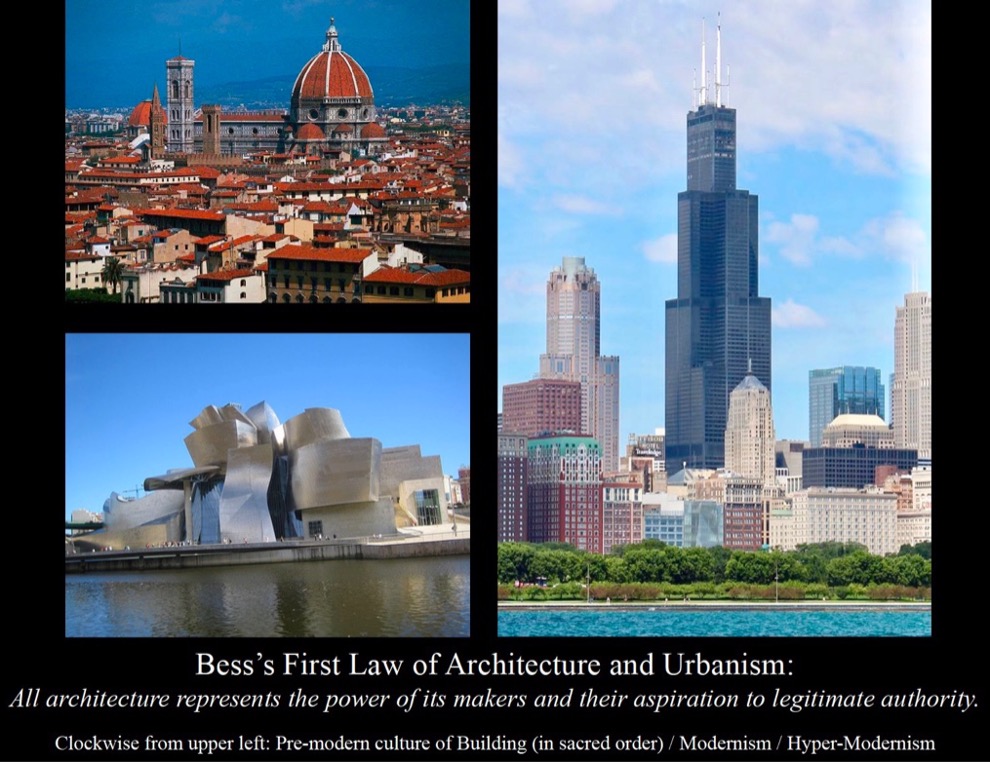

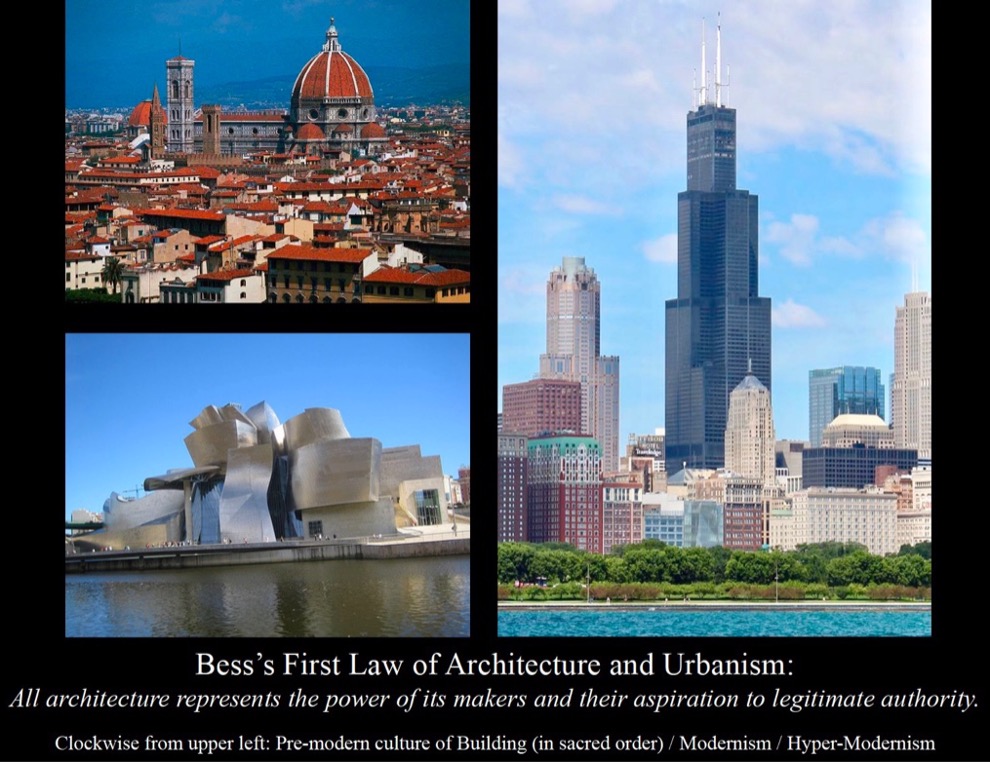

In what follows I want to discuss the political-but-not-partisanly-political nature of pre-modernist traditions of architecture and urban design as civic arts in sacred order, starting with a proposition I probably too rashly call Bess’s First Law of Architecture and Urbanism. It goes like this:

All architecture represents the power of its makers and their aspiration to legitimate authority.1

By this I mean that the act of building has both practical and metaphysical implications. Building is a willful act of symbolic import, its symbolism sometimes intended and sometimes not, and never fixed; but all architecture expresses the power of its makers and their aspiration to legitimate authority. This is true not only of buildings but also public spaces, indeed of all human settlements. Their very existence presumes the power of human beings in the most elemental sense. More than this however, human beings attach moral significance to our buildings and landscapes. Legitimate authority is that moral “more than” mere power, more than the human capacity to will something and make it so. Legitimate authority is trustworthy power wed to moral virtue in service to shared communal ideals, a communal and metaphysical constraint upon and direction of human powers. In the realms of architecture and urbanism, aspiration to legitimate authority entails an ambition to unite beauty with goodness and truth.

Specific political meanings of buildings – typically multiple, and also subject to change over time – are neither inherent nor unimportant. Moreover, one can temporarily set political meanings aside in order to discuss the authority of architecture in terms of what I will call architecture’s internal objectives, i.e., the goods it seeks in terms of its own self-understanding. What makes architectural authority legitimate within its own self-understanding and frame of reference? The answers to this question vary according to classical humanist presuppositions, modernist presuppositions, and contemporary post-modernist presuppositions about the nature of architecture, human nature, and the nature of reality itself.2

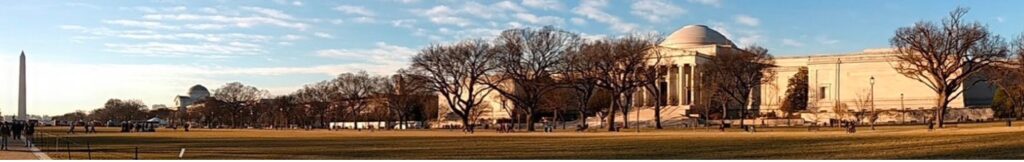

The goods of classical humanist architecture’s complex telos are often defined in historic commonsense Vitruvian terms of the durability, usefulness, and beauty of buildings in right relationship to each other, with these characteristics understood as objective goods. Indeed, it is a core and distinguishing contention of classicists – sometimes explicit but always at least implied – that the nature of beauty is objective, can be described, and that beauty in the public realm matters. Historically, classicism’s complex goods also in some way simultaneously represent, aspire to, and participate in some larger cosmic order the yearning for which constitutes a kind of transcendent utopianism – abstract phenomenological archi-speak for what Christians recognize as summum bonum, The City of God / New Jerusalem – partially but never completely realizable in this world. As a byproduct of these complex but holistic sensibilities, classical humanist architecture and urbanism, because pre-industrial and generally made from locally sourced low-embodied energy materials under conditions of scarcity, were also ‘environmentally friendly’ and ‘sustainably green’ without even trying. Classicism has likewise had a long time to refine its capacities for architectural excellence across scales, in modes austere to exuberant. There are good reasons classicism became the pre-eminent language of civic architecture, first in antiquity and later throughout the pre-modern western world.

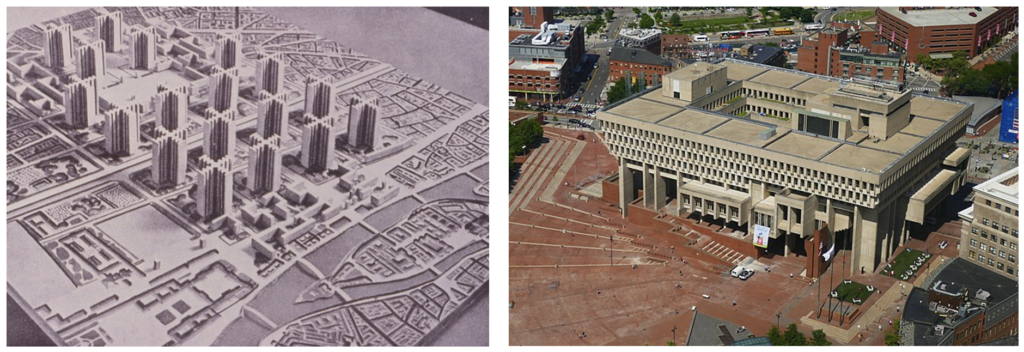

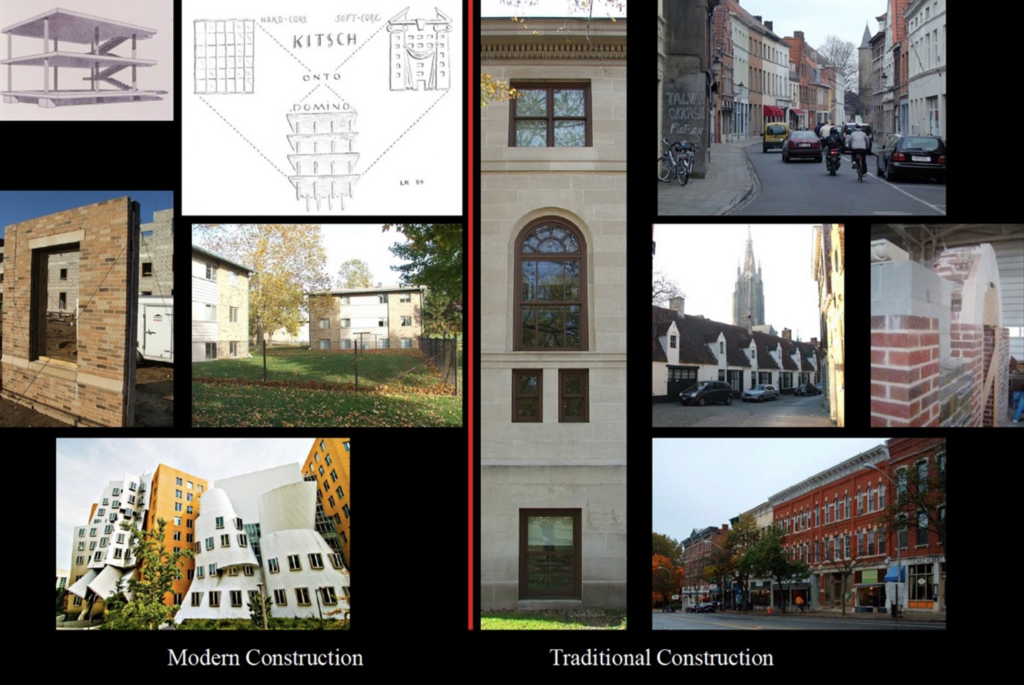

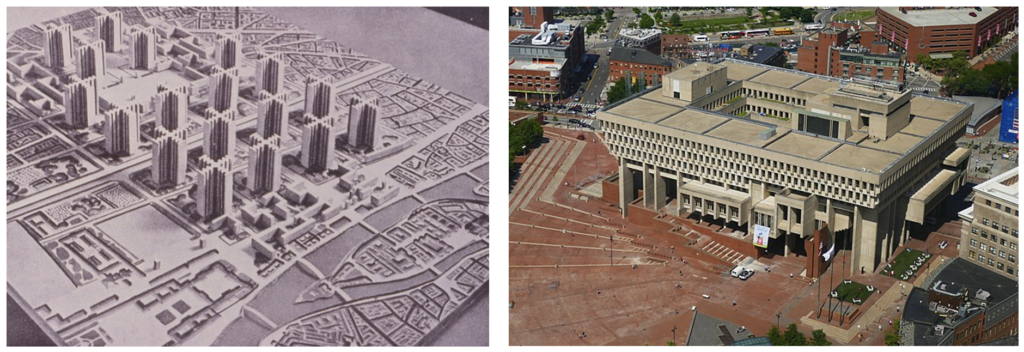

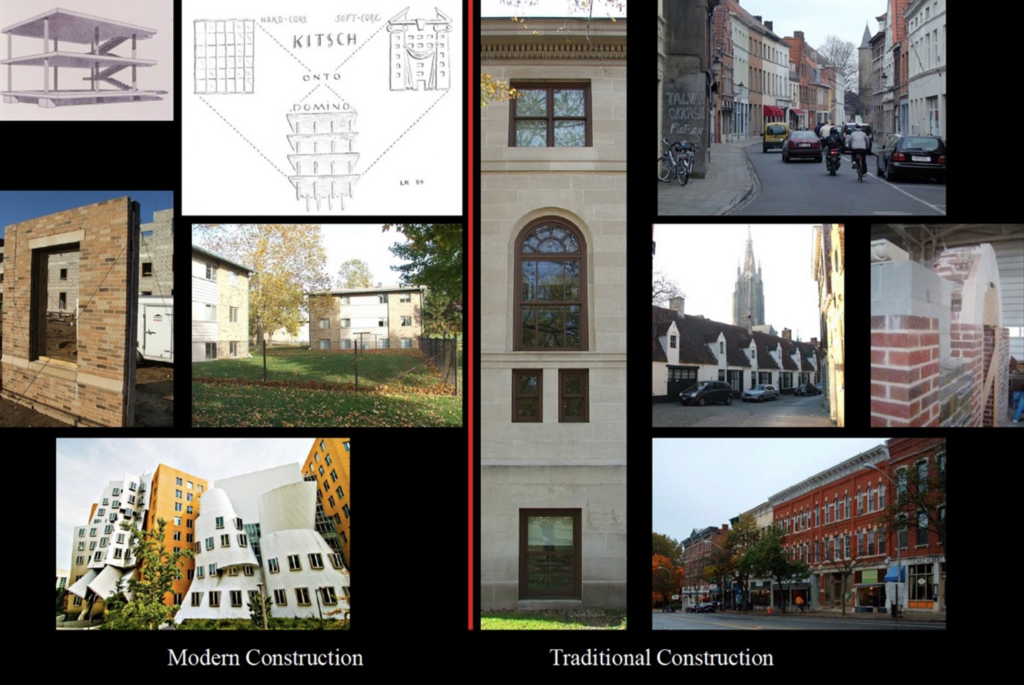

The industrial revolution and the rise of modernity – by which I mean specifically the rise of technological production and bureaucratic organization, their transformation of the economy, and subsequent transformations of human desire and imagination – have shaken classicism’s metaphysical realist foundations;3 and architectural modernism’s ideological presuppositions are different. Modernism is in certain ways an anti-classicism, the architectural equivalent of the French Revolution, though modernism shares with classicism both a teleological structure and a set of moral and aesthetic ideals. Nevertheless, modernism has proven itself capable of neither a civic architecture, nor a durable “background buildings” culture, nor a public realm that the former two create that are as rich in detail and extensive in range as modernism’s classical humanist predecessor.

And this I think is because modernism is a single intellectual and ideological error, of three sorts: metaphysical, anthropological, and constructional. Metaphysically, modernism’s utopian horizon is immanent rather than transcendent, its animating ideal subject to empirical falsification through physical decay and a susceptibility to modern political temptations both authoritarian and totalitarian. Anthropologically, modernism – unlike both classical humanism and actual human beings – is all utopia and no tradition, all hope and no memory. And constructionally, because modernism was ideologically committed to modern industrial materials and methods and to abstract forms – frames and “skins” and flat roofs as opposed to integral pre-modern bearing walls and roofs that shed water – and to utility but not ornament, modernism produces far too many buildings neither well-built nor much loved. Nor did the modernists anticipate the extensive environmental degradations that modern industrialization would bring, and in which modernism remains complicit. The best of the modernists did produce a distinctive aesthetic that is in fact beloved by many; and even in the economic downsizing that sixty years of falling global fertility rates ensures as our foreseeable future, it is possible to imagine architectural modernism as an aesthetic tradition ironically pursued as a niche market activity, modernism’s iconic works representing a standard of excellence to be emulated by designers and patrons understandably nostalgic for the middle decades of the 20th century, before the economic and environmental bills came due and the modern world went to hell.

Nevertheless, as a coherent intellectual and artistic worldview, as an ideology of progress, there can be no doubt that Mod is dead, done in by historical events; though it does sputter on, a default set of building practices bearing witness to and accelerating our culture’s race to the bottom. My suspicion is that future historians will recognize architectural modernism as a transitional body of theory and practice that in the middle years of the 20th century bridged the gap between the pre-modern classical humanist architecture and urban traditions that prevailed until just after World War I, and the rise of post-modern hypermodernism that began to emerge in the last decade of the 20th century.

A naïve modernism even now persists in the architectural profession and in many if not most contemporary schools of architecture; as governing assumptions for the latter’s accrediting agencies; and in our default construction practices. But our most elite and prestigious architecture schools and the campuses and cities in which their influence can be found have happily embraced hypermodernism, which is essentially modernism minus modernism’s confidence in its earlier moral, aesthetic and political agenda.

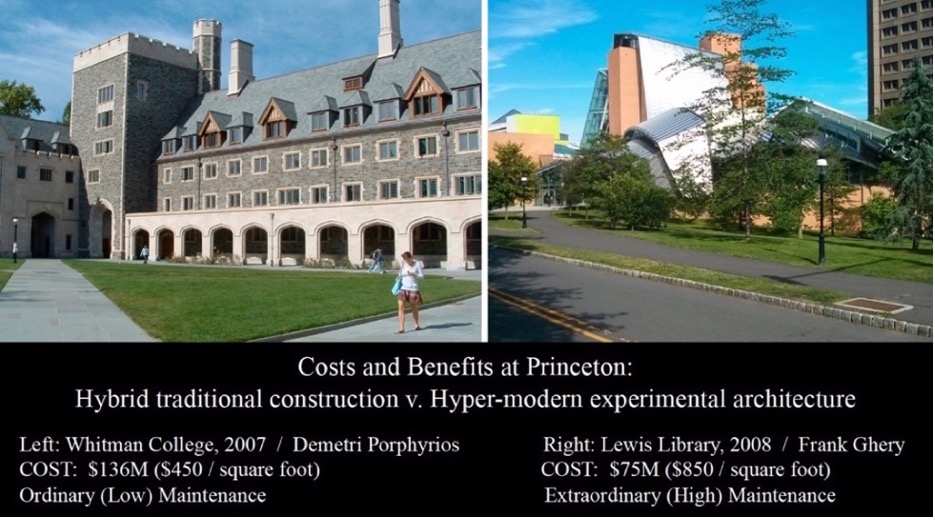

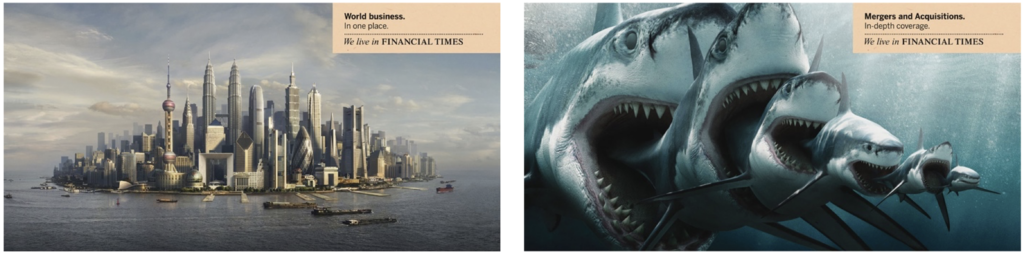

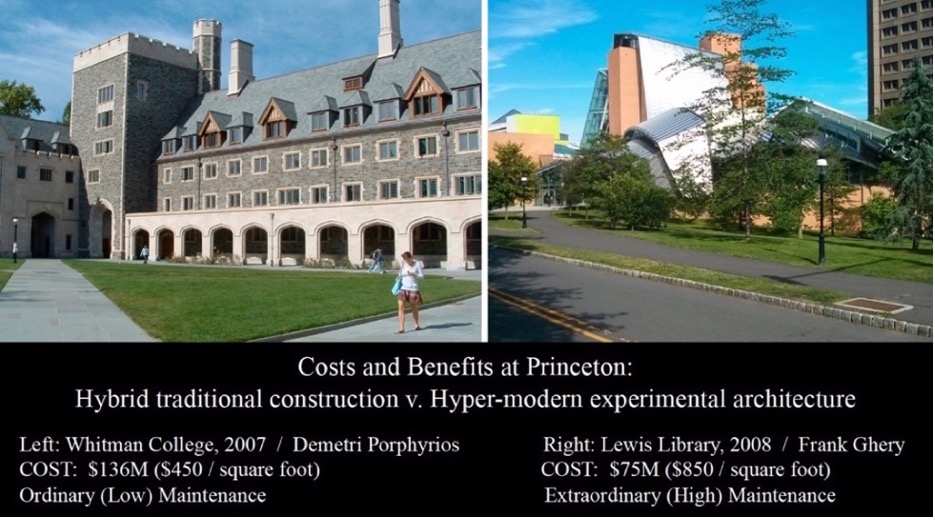

Seen another way however, in a Nietzschean post-modern way, hypermodernism is modernism unmasked. It is subjectivism, relativism, and individualism writ in and at the scale of buildings and cities, the architecture of the global economy that takes as premises certain modern material conditions and practices, and certain short-term aesthetic possibilities that follow therefrom. As performative art hypermodernism is a nihilistic and frequently narcissistic therapeutic exercise serving various crony-capital masters of the universe, toward the apparent end of entertaining atomized individuals and compensating them for their position in the global economy with buildings that either excite or baffle or both.4 The idea that either contemporary modernist or hyper-modernist architecture and urbanism are somehow more conducive than classical humanist architecture and urbanism to some recognizable historic form of human flourishing – or even somehow embodies and/or promotes greater “diversity” in either architecture or human relationships – is risible. (The smartest hypermodernists know this, and don’t care.) Nor must we allow politically progressive hyper-modernists – e.g., the patrons of the Pritzker Prize in Architecture, the winners of which vary in the quality of their architecture but are unfailingly modernist or hypermodernist in character and worldview – to kid either themselves or us: modern construction has long been and remains on a collision course with progressive environmentalism, climate change, and the high expense and maintenance costs of low durability modernist and hypermodernist architectural icons. But hypermodernism is now both an architectural attitude and a legal, academic and cultural regime. Few hypermodernist architects or patrons will voluntarily abandon their ideology and its perks, even in the face of mounting environmental, economic, and aesthetic pressures.

Part II: Where do we go from here?

The rest of this essay is indexed to forty-four slides that illustrate descriptions of the two projects that follow, linked HERE in this pdf document. Near the end of the description of the second project is a link to a two-minute project fly-through of the same.

Our Lady’s Plan of Chicago 2109

[slide 1] At this point I want to introduce two University of Notre Dame School of Architecture graduate studio proposals undertaken as visionary projects in response to the present debased state of American cities and landscapes.

One is at the scale of a modern metropolitan region covering 4000 square miles, and the other is at the scale of one-and-a-half city blocks of church-owned property covering eight acres. My purpose here is to argue that there is a lost but recoverable tradition of architecture that can comprehend and address the issues entailed by human place-making at each of these scales and in between, ranging from

- regional land use; to

- the physical form of cities, towns and villages and their component networks of streets and blocks; to

- both the preservation of existing monumental foreground buildings (“architecture”) and good background “vernacular” buildings on such blocks, and construction of new versions of each.

This architectural tradition can be characterized loosely but substantively as classical humanism, though by any other name it would be just as rosy. The two projects I am going to show are grounded in skepticism of both the existing merits and the future prospects of our modern industrial culture of construction. That culture, at global scale, relies on ever increasing quantities of industrially produced high-embodied energy materials, including putatively “eco-friendly” hi-tech products requiring complex processes of mineral extraction and processing, material assemblage, manufacture, and long-distance transportation. The apparent consequence, supported by an increasingly visible body of evidence, is that our post-1950 built environment is neither resilient nor sustainable, either economically or environmentally. Nor is it beautiful enough to warrant the affection that might inspire economic sacrifice to preserve it. All of which calls to mind Stein’s Law, articulated by Herbert Stein in the mid 1980s: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Now, for context, Stein was being both serious and ironic; and part of his irony was directed against those alarmists who were thinking that because something cannot go on forever, the time to stop it is now – immediately, and sometimes by any means necessary. And while I appreciate the truth of Stein’s Law and am sympathetic to Stein’s sentiment, I do think that if ruinous things are happening that should not continue even if they are popular, neither civilizational collapse nor political revolution are necessarily the most desirable courses of amelioration. The two projects that follow are intended as examples of serious but less drastic ameliorative alternatives.

[slide 2] Renewing an authentic human ecology that both nourishes the human soul and is consonant with our human vocation to be stewards of creation seems a daunting cultural and political project that nevertheless must largely occur (arguably can only occur) in situ: multiple steadfast exercises of justice, generosity, prudence, aesthetic judgment and skill, both individual and collective, appropriate to Max Weber’s famous pre-power-tool characterization of politics as “a slow boring of hard boards.”But some of the work of this cultural project must be visionary because any great cooperative project must begin with at least some provisional vision of its desired end.

Off and on for nearly fifteen years at the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, a select group of urban design students has been asked to imagine together and separately metropolitan Chicago at the bicentennial of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago – the latter arguably America’s greatest visionary urban project, and certainly the greatest since America’s Civil War – in an ongoing project called After Burnham: Our Lady’s Plan of Chicago 2109. [slide 3] In these Notre Dame urban design studios – perhaps six in all, engaging more than three dozen students – drawing upon classical humanist traditions of architecture and urban design and principles of Catholic social teaching, looking both backward and forward, the objective has been to envision Chicago in 2109 as a flourishing agrarian-urban unit – a regional federation of neo-Aristotelian πόλεις at metropolitan scale, but even at metropolitan scale characterized by beauty, solidarity, subsidiarity, environmental stewardship, and good law, a metropolis that in whole and in its parts both anticipates and sacramentally participates in the heavenly Jerusalem that in the Christian understanding of reality is the very telos of creation itself.

[slide 4] The Chicago 2109 project was prompted by a general dismay at what today’s most prominent architecture and urbanism have become; by a specific sadness about Chicago as a global city with a globally recognized skyline, at the same time bleeding population and teetering on the edge of financial insolvency into which it is surely going to plunge; and finally by the tendentious ideological character of the Chicago architectural establishment’s observance in 2009 of the Centennial of the Plan of Chicago. And so, Chicago 2109 was undertaken for several reasons:

- First, to critique what Chicago had become 100 years after Burnham and Bennett’s Plan of Chicago.

- [slide 5] Second, to critique the original Plan of Chicago itself.

- Third, to envision Chicago at the Bicentennial of the Plan and what Chicago might look like in 2109 by beginning with Chicago as it exists in the present,

- [slide 6] but guided over the next century by the comprehensive vision and classical humanist sensibilities of the 1909 Plan of Chicago as an authoritative reference point.

I also thought at the outset (and even now) that Notre Dame’s School of Architecture was uniquely positioned to undertake a project of this sort, both because classical humanist architectural sensibilities were deeply embedded in the School and because they could be grounded in the sacramental culture and metaphysical realist assumptions of the larger University community. In retrospect I may have overestimated the pervasiveness of these latter assumptions at Notre Dame, though Notre Dame remains an academic community in which the triumph of the therapeutic is not complete and the objective character of beauty, goodness, and truth remain arguable (and argued) propositions.

[slide 7] The 4000-square-mile metropolitan scale of the Chicago 2109 project causes many who first see it either to misunderstand or to mis-characterize it, most commonly to mistake it for a latter-day Robert Moses-like political proposal entailing extensive condemnation of private property and forced shut-downs of post-1950 automobile suburbs. But this is not correct. Compared to the modernist planning hubris on display in metropolitan Chicago in the 1950s, 60s and 70s – almost three decades of “urban renewal” and massive neighborhood dislocation that accompanied some seventy-five miles of interstate highway construction within Chicago’s city limits – Our Lady’s Plan of Chicago 2109is subsidiarity and limited government humility itself. How so?

First, it proposes no takings of private land in either city or suburb, and condemns no existing buildings; and second, although its narrative of the future is surely one of decline and revival throughout metropolitan Chicago, the decline it presumes is not something wished-for but rather is already happening of its own accord; and Chicago 2109 presumes that post-war automobile suburbs in their current form will have definitively failed by the beginning of the 22nd century, primarily for two reasons.

The first is demographic, related to consecutive generations of below replacement fertility rates in the industrialized world that carry certain fixed demographic consequences that will become increasingly apparent as the American Baby Boom generation dies off. The second – related to the first – is economic, having to do with maintenance-and-repair costs of post-1945 America’s empire of far-flung suburban roads and sewers that vastly exceed the financial capacity of suburbia’s low-population-density tax-base. This is not to say our cities are currently in great shape either, only that the kinds of sustainable and resilient regional scale changes we imagine require us to do something different than we are now doing.

Chicago 2109 thus is not to be understood as a single ‘big plan’ to be imposed from on high, but rather as a visionary framework for a thousand Chicago-related projects. Moreover, its fundamental sensibilities are necessarily modest. The 1909 Plan of Chicago was conceived when Chicago was the fastest growing city in the world, and rich. Chicago 2109 is conceived in a time of shrinkage and scarcity, not to mention environmental degradation (of which Chicago has a long history). What Chicago 2109 presumes therefore (and requires) is an accumulation of prudential policy judgments [Slide 8]:

- Build on Chicago’s existing strengths, especially rail transit and proximity to fresh water and good agricultural land.

- Cut suburban losses, re-densify around existing commuter rail lines in known building and neighborhood types, and reclaim failed automobile suburbs as rural and agricultural landscape.

- Adopt form-based zoning codes based on density and building types to replace single-use zoning codes.

- In low-rise (walk-up) building districts, mandate (or at least incentivize) by law the use of a limited range of regionally sourced low-embodied-energy building materials (stone, brick, wood timbers, slate and clay tiles, etc.)

- Create a more equitable regional regime of land value taxation that rewards agricultural and entrepreneurial activity and increases home ownership and housing supply by penalizing speculation in land.

- Make land value, natural resources and Pigouvian (sin) taxes foundational for governmental revenue at all levels, replacing as many other taxes as feasible – initially the property tax, but followed by sales tax, income tax, business tax, and capital gains tax if and as possible.

What might this metropolitan-scale transformation look like? Though modest about methods, the scope and ambition of Chicago 2109 are holistic and comprehensive, addressing issues ranging from land use; [slide 9] to settlement type size, density, form and structure; [slide 10] to regional transportation and its relationship to land use; [slide 11] to storm and wastewater management specific to both the City of Chicago and the metro Chicago region, respectively; [slide 12] to recovery of in-City land lost to interstate highways in the era of 20th century urban renewal; [slide 13] to historic regional city housing types across an urban transect [slide 14] and their effects upon regional and city population density and the recovery of natural and agricultural land; [slides 15-17] and finally, to the symbolic content of Chicago’s formal order and its relationship not only to civic order but to sacred order. Addressing a conspicuous lacuna in the Plan of Chicago – and in spite of both the sacred origins of classical architecture and Burnham’s own Swedenborgian Christian piety – Chicago 2109 proposes to establish a north-south “sacred” cross-axis at the heart of Chicago’s historic center [slides 18-19] that gives places of prominence to representative houses of worship from Chicago’s existing religious communities [slide 20] and is at the same time a physical embodiment in the public realm of America’s historic principles of religious non-establishment and free exercise. This particular proposal to acknowledge sacred order in the formal order of a major American city is obviously more rooted in both Dignitatis Humanae, certain traditions of American liberalism (mainstream traditions of American liberalism I would argue) and the formal precedent of religious pluralism in Savannah, Georgia than in any of today’s neo-traditional integralist aspirations.5

St. Patrick’s / St. Hedwig’s Parish, South Bend, Indiana

[slide 21] The Chicago 2109 project engages 4000 square miles of northeast Illinois and is a product of multiple design studios over several years. The second project engages a mere eight acres on the southwest edge of downtown South Bend, Indiana and is the work of Class of 2023 graduate students Patrick Beck, Shauni Priyam Sikder, and Sam Usle, in one design studio over the course of six weeks early in 2022, assisted by three Notre Dame alumni in a weekend design workshop early in the project. The students came to this project with prior studio experience of exercises designing small scale schematic urban interventions, but none requiring design work constrained by real world zoning codes (let alone the more daunting task of differentiating good zoning codes from bad). Nevertheless, for a six-week schematic exercise, the student work is meticulous in addressing project details down to and including zoning, site subdivision and parcelization, and provision of interior block off-street parking in a new neighborhood precinct that simultaneously diminishes the need for driving.

[slide 22] The existing site is a classic 1960s era “urban renewal” ruin, and the studio project was imagined as a model for the development of underused church properties. Simultaneously modest and audacious, it proposes a small neighborhood precinct around two existing late 19th century churches located a block apart and standing virtually alone on their eight-acre church-owned property. On the vacant land surrounding the churches the students have proposed to fill it with 60-100 new mission-related dwelling units (e.g. for school personnel, married university students, etc.) in a variety of small but elegant and durable buildings designed to accommodate an on-site gross residential population density of 7.5 – 12.5 dwelling units per acre; plus recreational fields and a 40,000 square foot K-12 school in two buildings for an existing Catholic Classical Academy; 11,000 square feet of retail space; and – perhaps most importantly – a sequence of internal block public spaces that all together comprise a beautiful neighborhood precinct that highlights the presence and seeks to revive the fortunes of the two churches (now one parish) and their larger neighborhood context.

[slides 23-26] European & American interior block precedent studies: Courtyards and Alleys.

[slide 27] Small houses, 20’x30’ modules (600-900sf / 1200-1800sf).

[slides 28-30] Durable construction model: American College of the Building Arts.

[slides 31-41] Student Plans – Demolition and Four-Phase site buildout.

[slides 42-44] Student Plans — Project zoning, Mid-block parcelization, Off-street parking.

Project Fly-through / 2-minute video (not to be missed; all buildings but the two churches are new)

In the context of South Bend’s market-driven and proactive city-facilitated development, this project afforded students an opportunity to explore how ecclesiastical landowners — by virtue of their non-profit status and recognizing that virtually every property-owning religious community in the United States is a potential Community Land Trust that with good design guidance has the ability to make modest, high-quality, below-market-rate mission-related housing – might be able to develop their underused properties differently from current industry-standard models of financing and development. They show how religious communities, by being conscientious about the use of their land and adopting a big-picture approach to design and construction, possess the opportunity to remake village, town, and city neighborhood precincts incrementally, by multiple actors, in ways that enable parish and congregational communities to better fulfill their evangelical, pastoral, charitable, familial, artistic, educational and entrepreneurial callings in ways simultaneously productive, beautiful and didactic (cf. footnote #1).

The trajectories of secularist culture, the global economy, hypermodern architecture, and suburban sprawl increasingly appear spiritually, economically, environmentally, and anthropologically unsustainable, and no one involved with these projectsthinks achieving either the regional goals of Chicago 2109 or the parish and neighborhood goals of the South Bend project will be easy. However, Christians need not agree with Pope Francis’s political prescriptions in Laudato Si’ to recognize the theological and anthropological truths at its heart: that Nature is most truly understood as Creation; that Man is an intermediate being with a duty to steward nature (with implications for both nature and for us); and that “everything is connected.” In this world walkable mixed-use villages, towns and city neighborhoods are the primary ways human animals employ productive and practical reason to occupy the landscape well. If human beings are to live harmoniously in, with, and from nature, both frugally and abundantly, it will likely be in these physical forms of community. In such traditional settlements just and generous communities create economic, social, and spiritual capital, manage their adjacent landscapes well, make durable and beautiful buildings and locate the most important of them in places of honor. Such physical patterns elevate us, and Christians can begin to recover them today even in small parishes and congregations, and of course not only Christians. Any small community of any size can become part of a polis, that earthly “community of communities” Aristotle identified as the highest because it exists to promote human flourishing, the highest good human beings can achieve in this life – an estimation of the City of Man that even Augustine endorsed insofar as it promoted “the end [telos / finis] of earthly peace.”

But Augustine also knew what all Christians should also know: that our best earthly cities anticipate, and may even in some mysterious way participate in, that larger urban cosmic telos that is the City of God.

Coda:

[Granting]the principle of local loyalty, we are engaged in a search for the appropriate geographical unit . . . for a non-arbitrary alternative to the nation-state. Instead of looking more widely, I suggest, we should look nearer at home, to the “local” in a more restricted sense. The scholastic tradition of Christian political thought used to hold a doctrine . . . that decisions ought to be taken on as small a scale as was reasonable, it being the task of higher orders of government to afford “help” (subsidium) to lower orders, not to assume their responsibilities from them. There is no absolute way of defining what this reasonably small-scale unit of decision-making should be…. But we do have a notion . . . of a community which is self-sufficient [not] in the sense that it could isolate itself and do without mercantile and cultural interaction with other communities (for there is no community which could safely do that); but self-sufficient in the sense that its members can find within its bounds the resources they need for the pursuit of their lives: food, work, education, leisure, culture, and a land in which to move around and take delight. The scholastic understanding taught that the community which was, in this sense, self-sufficient or “perfect,” generated within itself its own political authority…. In the self-sufficient local community there is a resource of political authority waiting to be rediscovered; and the Christian church, which has striven to be both universal and local . . . is in a good position to point the way. Out of the service of the locality we may hope to see new political creativities released.

– Oliver O’Donovan, “The Loss of a Sense of Place,” (Bonds of Imperfection, 1989)

Philip Bess is Professor of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame.

NOTES:

[1] If, as I suspect, there are readers with a particular interest in the aesthetic import of Christian church architecture, I invite consideration of and (if desired) commentary upon the proposition that follows, my own further elucidation of which here would further surpass the assigned limits of this introductory essay (and also perhaps my competence). I presume however we will not recover a good culture of church buildings apart from recovering a good culture of building.

Christian houses of worship and their ancillary buildings and spaces are properly understood as communal statements of faith that invite both Christians and non-believers to acknowledge and worship God. When such buildings and spaces are beautiful, durable, and shape and ornament the public realm, they reinforce the faith of Christians, open the minds of non-believers to more sympathetic consideration of Christian truth claims, foreshadow the New Jerusalem as eschatological gift, and participate in the New Jerusalem as sacramental presence.

[2] The incoherence of contemporary architectural discourse in particular, manifested directly in the incoherence of our built environment, reflects the absence of any widely shared architectural-and-urban telos beyond the bottom line of developer spreadsheets, the life-safety criteria of modern building codes, and the off-street parking mandates of use-based zoning.

[3] If the late sociologist Peter Berger is correct, modern metaphysical uncertainty is caused less by advances in science than by the relativizing effects of cultural and religious pluralism characteristic of modern societies that make metaphysical certitude inherently more difficult. Sadly, Berger died before he could write a treatise on the social reality of construction.

[4] The cumulative effect is summarized in Bess’s Second Law of Architecture and Urbanism, which states that

A widespread desire for and expectation of social predictability from everyone else (a culture of bureaucracy), combined with a widespread desire for and expectation of maximum freedom for oneself (a culture of personal autonomy), will never produce a beautiful, coherent, and intelligible public realm.

[5] My not entirely unsympathetic view of Christian integralism is that it is properly regarded as an eschatological condition (certainly Catholic, but also catholic) rather than a plausible or human historical possibility at the scale of a modern, pluralistic, continental nation state. Until the eschaton however, in pluralistic societies, the American constitutional tradition of non-establishment / free exercise — in which the state demurs from adjudicating religious truth claims owing to its lack of competence to do so — still seems to me the best way so far for human beings to collectively acknowledge the sacred order in which creation itself is grounded while at the same time respecting the inherent dignity of human beings, our multiple religious traditions and communities, and the different ways in which human beings understand the individual and communal obligations that follow from our different understandings of God and the details of the sacred cosmos within which we exist.

Contemporary Western society is marked by a loss of the sense of place, and its intellectual traditions, far from controlling this loss, have encouraged it. The still persistent concerns which we have for the places about which we care are therefore inadequately represented in our formal political discourse; with the result that, being neither recognized nor properly criticized, they build up frustrations which break out in disruptive aspirations and claims which are less natural and less reasonable. Humanity is not fitted to live in placeless communities, the creations of pure human will unmediated through natural circumstance, the communities which are offered to us by the liberal tradition of political theory.

- Oliver O’Donovan, “The Loss of a Sense of Place,” (Bonds of Imperfection, 1989)

Part I: Here we are…

I begin with a passage for this audience, taken from a lecture given in 1986 at Queen’s University, Belfast, by Anglican theologian and ethicist Oliver O’Donovan, simply as an outside-the-architecture-guild confirmation of a baseline premise for what follows, viz. the miserable state of the built environment the modern west has been making (and exporting) since the end of World War II.

In what follows I want to discuss the political-but-not-partisanly-political nature of pre-modernist traditions of architecture and urban design as civic arts in sacred order, starting with a proposition I probably too rashly call Bess’s First Law of Architecture and Urbanism. It goes like this:

All architecture represents the power of its makers and their aspiration to legitimate authority.1

By this I mean that the act of building has both practical and metaphysical implications. Building is a willful act of symbolic import, its symbolism sometimes intended and sometimes not, and never fixed; but all architecture expresses the power of its makers and their aspiration to legitimate authority. This is true not only of buildings but also public spaces, indeed of all human settlements. Their very existence presumes the power of human beings in the most elemental sense. More than this however, human beings attach moral significance to our buildings and landscapes. Legitimate authority is that moral “more than” mere power, more than the human capacity to will something and make it so. Legitimate authority is trustworthy power wed to moral virtue in service to shared communal ideals, a communal and metaphysical constraint upon and direction of human powers. In the realms of architecture and urbanism, aspiration to legitimate authority entails an ambition to unite beauty with goodness and truth.

Specific political meanings of buildings – typically multiple, and also subject to change over time – are neither inherent nor unimportant. Moreover, one can temporarily set political meanings aside in order to discuss the authority of architecture in terms of what I will call architecture’s internal objectives, i.e., the goods it seeks in terms of its own self-understanding. What makes architectural authority legitimate within its own self-understanding and frame of reference? The answers to this question vary according to classical humanist presuppositions, modernist presuppositions, and contemporary post-modernist presuppositions about the nature of architecture, human nature, and the nature of reality itself.2

The goods of classical humanist architecture’s complex telos are often defined in historic commonsense Vitruvian terms of the durability, usefulness, and beauty of buildings in right relationship to each other, with these characteristics understood as objective goods. Indeed, it is a core and distinguishing contention of classicists – sometimes explicit but always at least implied – that the nature of beauty is objective, can be described, and that beauty in the public realm matters. Historically, classicism’s complex goods also in some way simultaneously represent, aspire to, and participate in some larger cosmic order the yearning for which constitutes a kind of transcendent utopianism – abstract phenomenological archi-speak for what Christians recognize as summum bonum, The City of God / New Jerusalem – partially but never completely realizable in this world. As a byproduct of these complex but holistic sensibilities, classical humanist architecture and urbanism, because pre-industrial and generally made from locally sourced low-embodied energy materials under conditions of scarcity, were also ‘environmentally friendly’ and ‘sustainably green’ without even trying. Classicism has likewise had a long time to refine its capacities for architectural excellence across scales, in modes austere to exuberant. There are good reasons classicism became the pre-eminent language of civic architecture, first in antiquity and later throughout the pre-modern western world.

The industrial revolution and the rise of modernity – by which I mean specifically the rise of technological production and bureaucratic organization, their transformation of the economy, and subsequent transformations of human desire and imagination – have shaken classicism’s metaphysical realist foundations;3 and architectural modernism’s ideological presuppositions are different. Modernism is in certain ways an anti-classicism, the architectural equivalent of the French Revolution, though modernism shares with classicism both a teleological structure and a set of moral and aesthetic ideals. Nevertheless, modernism has proven itself capable of neither a civic architecture, nor a durable “background buildings” culture, nor a public realm that the former two create that are as rich in detail and extensive in range as modernism’s classical humanist predecessor.

And this I think is because modernism is a single intellectual and ideological error, of three sorts: metaphysical, anthropological, and constructional. Metaphysically, modernism’s utopian horizon is immanent rather than transcendent, its animating ideal subject to empirical falsification through physical decay and a susceptibility to modern political temptations both authoritarian and totalitarian. Anthropologically, modernism – unlike both classical humanism and actual human beings – is all utopia and no tradition, all hope and no memory. And constructionally, because modernism was ideologically committed to modern industrial materials and methods and to abstract forms – frames and “skins” and flat roofs as opposed to integral pre-modern bearing walls and roofs that shed water – and to utility but not ornament, modernism produces far too many buildings neither well-built nor much loved. Nor did the modernists anticipate the extensive environmental degradations that modern industrialization would bring, and in which modernism remains complicit. The best of the modernists did produce a distinctive aesthetic that is in fact beloved by many; and even in the economic downsizing that sixty years of falling global fertility rates ensures as our foreseeable future, it is possible to imagine architectural modernism as an aesthetic tradition ironically pursued as a niche market activity, modernism’s iconic works representing a standard of excellence to be emulated by designers and patrons understandably nostalgic for the middle decades of the 20th century, before the economic and environmental bills came due and the modern world went to hell.

Nevertheless, as a coherent intellectual and artistic worldview, as an ideology of progress, there can be no doubt that Mod is dead, done in by historical events; though it does sputter on, a default set of building practices bearing witness to and accelerating our culture’s race to the bottom. My suspicion is that future historians will recognize architectural modernism as a transitional body of theory and practice that in the middle years of the 20th century bridged the gap between the pre-modern classical humanist architecture and urban traditions that prevailed until just after World War I, and the rise of post-modern hypermodernism that began to emerge in the last decade of the 20th century.

A naïve modernism even now persists in the architectural profession and in many if not most contemporary schools of architecture; as governing assumptions for the latter’s accrediting agencies; and in our default construction practices. But our most elite and prestigious architecture schools and the campuses and cities in which their influence can be found have happily embraced hypermodernism, which is essentially modernism minus modernism’s confidence in its earlier moral, aesthetic and political agenda.

Seen another way however, in a Nietzschean post-modern way, hypermodernism is modernism unmasked. It is subjectivism, relativism, and individualism writ in and at the scale of buildings and cities, the architecture of the global economy that takes as premises certain modern material conditions and practices, and certain short-term aesthetic possibilities that follow therefrom. As performative art hypermodernism is a nihilistic and frequently narcissistic therapeutic exercise serving various crony-capital masters of the universe, toward the apparent end of entertaining atomized individuals and compensating them for their position in the global economy with buildings that either excite or baffle or both.4 The idea that either contemporary modernist or hyper-modernist architecture and urbanism are somehow more conducive than classical humanist architecture and urbanism to some recognizable historic form of human flourishing – or even somehow embodies and/or promotes greater “diversity” in either architecture or human relationships – is risible. (The smartest hypermodernists know this, and don’t care.) Nor must we allow politically progressive hyper-modernists – e.g., the patrons of the Pritzker Prize in Architecture, the winners of which vary in the quality of their architecture but are unfailingly modernist or hypermodernist in character and worldview – to kid either themselves or us: modern construction has long been and remains on a collision course with progressive environmentalism, climate change, and the high expense and maintenance costs of low durability modernist and hypermodernist architectural icons. But hypermodernism is now both an architectural attitude and a legal, academic and cultural regime. Few hypermodernist architects or patrons will voluntarily abandon their ideology and its perks, even in the face of mounting environmental, economic, and aesthetic pressures.

Part II: Where do we go from here?

The rest of this essay is indexed to forty-four slides that illustrate descriptions of the two projects that follow, linked HERE in this pdf document. Near the end of the description of the second project is a link to a two-minute project fly-through of the same.

Our Lady’s Plan of Chicago 2109

[slide 1] At this point I want to introduce two University of Notre Dame School of Architecture graduate studio proposals undertaken as visionary projects in response to the present debased state of American cities and landscapes.

One is at the scale of a modern metropolitan region covering 4000 square miles, and the other is at the scale of one-and-a-half city blocks of church-owned property covering eight acres. My purpose here is to argue that there is a lost but recoverable tradition of architecture that can comprehend and address the issues entailed by human place-making at each of these scales and in between, ranging from

- regional land use; to

- the physical form of cities, towns and villages and their component networks of streets and blocks; to

- both the preservation of existing monumental foreground buildings (“architecture”) and good background “vernacular” buildings on such blocks, and construction of new versions of each.

This architectural tradition can be characterized loosely but substantively as classical humanism, though by any other name it would be just as rosy. The two projects I am going to show are grounded in skepticism of both the existing merits and the future prospects of our modern industrial culture of construction. That culture, at global scale, relies on ever increasing quantities of industrially produced high-embodied energy materials, including putatively “eco-friendly” hi-tech products requiring complex processes of mineral extraction and processing, material assemblage, manufacture, and long-distance transportation. The apparent consequence, supported by an increasingly visible body of evidence, is that our post-1950 built environment is neither resilient nor sustainable, either economically or environmentally. Nor is it beautiful enough to warrant the affection that might inspire economic sacrifice to preserve it. All of which calls to mind Stein’s Law, articulated by Herbert Stein in the mid 1980s: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Now, for context, Stein was being both serious and ironic; and part of his irony was directed against those alarmists who were thinking that because something cannot go on forever, the time to stop it is now – immediately, and sometimes by any means necessary. And while I appreciate the truth of Stein’s Law and am sympathetic to Stein’s sentiment, I do think that if ruinous things are happening that should not continue even if they are popular, neither civilizational collapse nor political revolution are necessarily the most desirable courses of amelioration. The two projects that follow are intended as examples of serious but less drastic ameliorative alternatives.

[slide 2] Renewing an authentic human ecology that both nourishes the human soul and is consonant with our human vocation to be stewards of creation seems a daunting cultural and political project that nevertheless must largely occur (arguably can only occur) in situ: multiple steadfast exercises of justice, generosity, prudence, aesthetic judgment and skill, both individual and collective, appropriate to Max Weber’s famous pre-power-tool characterization of politics as “a slow boring of hard boards.”But some of the work of this cultural project must be visionary because any great cooperative project must begin with at least some provisional vision of its desired end.

Off and on for nearly fifteen years at the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, a select group of urban design students has been asked to imagine together and separately metropolitan Chicago at the bicentennial of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago – the latter arguably America’s greatest visionary urban project, and certainly the greatest since America’s Civil War – in an ongoing project called After Burnham: Our Lady’s Plan of Chicago 2109. [slide 3] In these Notre Dame urban design studios – perhaps six in all, engaging more than three dozen students – drawing upon classical humanist traditions of architecture and urban design and principles of Catholic social teaching, looking both backward and forward, the objective has been to envision Chicago in 2109 as a flourishing agrarian-urban unit – a regional federation of neo-Aristotelian πόλεις at metropolitan scale, but even at metropolitan scale characterized by beauty, solidarity, subsidiarity, environmental stewardship, and good law, a metropolis that in whole and in its parts both anticipates and sacramentally participates in the heavenly Jerusalem that in the Christian understanding of reality is the very telos of creation itself.

[slide 4] The Chicago 2109 project was prompted by a general dismay at what today’s most prominent architecture and urbanism have become; by a specific sadness about Chicago as a global city with a globally recognized skyline, at the same time bleeding population and teetering on the edge of financial insolvency into which it is surely going to plunge; and finally by the tendentious ideological character of the Chicago architectural establishment’s observance in 2009 of the Centennial of the Plan of Chicago. And so, Chicago 2109 was undertaken for several reasons:

- First, to critique what Chicago had become 100 years after Burnham and Bennett’s Plan of Chicago.

- [slide 5] Second, to critique the original Plan of Chicago itself.

- Third, to envision Chicago at the Bicentennial of the Plan and what Chicago might look like in 2109 by beginning with Chicago as it exists in the present,

- [slide 6] but guided over the next century by the comprehensive vision and classical humanist sensibilities of the 1909 Plan of Chicago as an authoritative reference point.

I also thought at the outset (and even now) that Notre Dame’s School of Architecture was uniquely positioned to undertake a project of this sort, both because classical humanist architectural sensibilities were deeply embedded in the School and because they could be grounded in the sacramental culture and metaphysical realist assumptions of the larger University community. In retrospect I may have overestimated the pervasiveness of these latter assumptions at Notre Dame, though Notre Dame remains an academic community in which the triumph of the therapeutic is not complete and the objective character of beauty, goodness, and truth remain arguable (and argued) propositions.

[slide 7] The 4000-square-mile metropolitan scale of the Chicago 2109 project causes many who first see it either to misunderstand or to mis-characterize it, most commonly to mistake it for a latter-day Robert Moses-like political proposal entailing extensive condemnation of private property and forced shut-downs of post-1950 automobile suburbs. But this is not correct. Compared to the modernist planning hubris on display in metropolitan Chicago in the 1950s, 60s and 70s – almost three decades of “urban renewal” and massive neighborhood dislocation that accompanied some seventy-five miles of interstate highway construction within Chicago’s city limits – Our Lady’s Plan of Chicago 2109is subsidiarity and limited government humility itself. How so?

First, it proposes no takings of private land in either city or suburb, and condemns no existing buildings; and second, although its narrative of the future is surely one of decline and revival throughout metropolitan Chicago, the decline it presumes is not something wished-for but rather is already happening of its own accord; and Chicago 2109 presumes that post-war automobile suburbs in their current form will have definitively failed by the beginning of the 22nd century, primarily for two reasons.

The first is demographic, related to consecutive generations of below replacement fertility rates in the industrialized world that carry certain fixed demographic consequences that will become increasingly apparent as the American Baby Boom generation dies off. The second – related to the first – is economic, having to do with maintenance-and-repair costs of post-1945 America’s empire of far-flung suburban roads and sewers that vastly exceed the financial capacity of suburbia’s low-population-density tax-base. This is not to say our cities are currently in great shape either, only that the kinds of sustainable and resilient regional scale changes we imagine require us to do something different than we are now doing.

Chicago 2109 thus is not to be understood as a single ‘big plan’ to be imposed from on high, but rather as a visionary framework for a thousand Chicago-related projects. Moreover, its fundamental sensibilities are necessarily modest. The 1909 Plan of Chicago was conceived when Chicago was the fastest growing city in the world, and rich. Chicago 2109 is conceived in a time of shrinkage and scarcity, not to mention environmental degradation (of which Chicago has a long history). What Chicago 2109 presumes therefore (and requires) is an accumulation of prudential policy judgments [Slide 8]:

- Build on Chicago’s existing strengths, especially rail transit and proximity to fresh water and good agricultural land.

- Cut suburban losses, re-densify around existing commuter rail lines in known building and neighborhood types, and reclaim failed automobile suburbs as rural and agricultural landscape.

- Adopt form-based zoning codes based on density and building types to replace single-use zoning codes.

- In low-rise (walk-up) building districts, mandate (or at least incentivize) by law the use of a limited range of regionally sourced low-embodied-energy building materials (stone, brick, wood timbers, slate and clay tiles, etc.)

- Create a more equitable regional regime of land value taxation that rewards agricultural and entrepreneurial activity and increases home ownership and housing supply by penalizing speculation in land.

- Make land value, natural resources and Pigouvian (sin) taxes foundational for governmental revenue at all levels, replacing as many other taxes as feasible – initially the property tax, but followed by sales tax, income tax, business tax, and capital gains tax if and as possible.

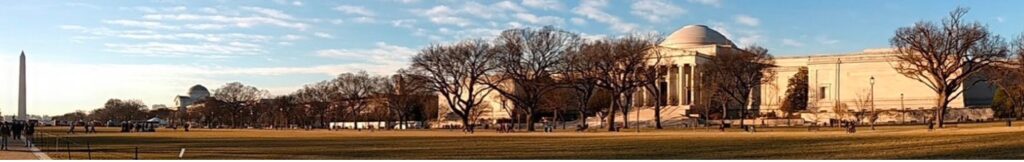

What might this metropolitan-scale transformation look like? Though modest about methods, the scope and ambition of Chicago 2109 are holistic and comprehensive, addressing issues ranging from land use; [slide 9] to settlement type size, density, form and structure; [slide 10] to regional transportation and its relationship to land use; [slide 11] to storm and wastewater management specific to both the City of Chicago and the metro Chicago region, respectively; [slide 12] to recovery of in-City land lost to interstate highways in the era of 20th century urban renewal; [slide 13] to historic regional city housing types across an urban transect [slide 14] and their effects upon regional and city population density and the recovery of natural and agricultural land; [slides 15-17] and finally, to the symbolic content of Chicago’s formal order and its relationship not only to civic order but to sacred order. Addressing a conspicuous lacuna in the Plan of Chicago – and in spite of both the sacred origins of classical architecture and Burnham’s own Swedenborgian Christian piety – Chicago 2109 proposes to establish a north-south “sacred” cross-axis at the heart of Chicago’s historic center [slides 18-19] that gives places of prominence to representative houses of worship from Chicago’s existing religious communities [slide 20] and is at the same time a physical embodiment in the public realm of America’s historic principles of religious non-establishment and free exercise. This particular proposal to acknowledge sacred order in the formal order of a major American city is obviously more rooted in both Dignitatis Humanae, certain traditions of American liberalism (mainstream traditions of American liberalism I would argue) and the formal precedent of religious pluralism in Savannah, Georgia than in any of today’s neo-traditional integralist aspirations.5

St. Patrick’s / St. Hedwig’s Parish, South Bend, Indiana

[slide 21] The Chicago 2109 project engages 4000 square miles of northeast Illinois and is a product of multiple design studios over several years. The second project engages a mere eight acres on the southwest edge of downtown South Bend, Indiana and is the work of Class of 2023 graduate students Patrick Beck, Shauni Priyam Sikder, and Sam Usle, in one design studio over the course of six weeks early in 2022, assisted by three Notre Dame alumni in a weekend design workshop early in the project. The students came to this project with prior studio experience of exercises designing small scale schematic urban interventions, but none requiring design work constrained by real world zoning codes (let alone the more daunting task of differentiating good zoning codes from bad). Nevertheless, for a six-week schematic exercise, the student work is meticulous in addressing project details down to and including zoning, site subdivision and parcelization, and provision of interior block off-street parking in a new neighborhood precinct that simultaneously diminishes the need for driving.

[slide 22] The existing site is a classic 1960s era “urban renewal” ruin, and the studio project was imagined as a model for the development of underused church properties. Simultaneously modest and audacious, it proposes a small neighborhood precinct around two existing late 19th century churches located a block apart and standing virtually alone on their eight-acre church-owned property. On the vacant land surrounding the churches the students have proposed to fill it with 60-100 new mission-related dwelling units (e.g. for school personnel, married university students, etc.) in a variety of small but elegant and durable buildings designed to accommodate an on-site gross residential population density of 7.5 – 12.5 dwelling units per acre; plus recreational fields and a 40,000 square foot K-12 school in two buildings for an existing Catholic Classical Academy; 11,000 square feet of retail space; and – perhaps most importantly – a sequence of internal block public spaces that all together comprise a beautiful neighborhood precinct that highlights the presence and seeks to revive the fortunes of the two churches (now one parish) and their larger neighborhood context.

[slides 23-26] European & American interior block precedent studies: Courtyards and Alleys.

[slide 27] Small houses, 20’x30’ modules (600-900sf / 1200-1800sf).

[slides 28-30] Durable construction model: American College of the Building Arts.

[slides 31-41] Student Plans – Demolition and Four-Phase site buildout.

[slides 42-44] Student Plans -- Project zoning, Mid-block parcelization, Off-street parking.

Project Fly-through / 2-minute video (not to be missed; all buildings but the two churches are new)

In the context of South Bend’s market-driven and proactive city-facilitated development, this project afforded students an opportunity to explore how ecclesiastical landowners -- by virtue of their non-profit status and recognizing that virtually every property-owning religious community in the United States is a potential Community Land Trust that with good design guidance has the ability to make modest, high-quality, below-market-rate mission-related housing – might be able to develop their underused properties differently from current industry-standard models of financing and development. They show how religious communities, by being conscientious about the use of their land and adopting a big-picture approach to design and construction, possess the opportunity to remake village, town, and city neighborhood precincts incrementally, by multiple actors, in ways that enable parish and congregational communities to better fulfill their evangelical, pastoral, charitable, familial, artistic, educational and entrepreneurial callings in ways simultaneously productive, beautiful and didactic (cf. footnote #1).

The trajectories of secularist culture, the global economy, hypermodern architecture, and suburban sprawl increasingly appear spiritually, economically, environmentally, and anthropologically unsustainable, and no one involved with these projectsthinks achieving either the regional goals of Chicago 2109 or the parish and neighborhood goals of the South Bend project will be easy. However, Christians need not agree with Pope Francis’s political prescriptions in Laudato Si’ to recognize the theological and anthropological truths at its heart: that Nature is most truly understood as Creation; that Man is an intermediate being with a duty to steward nature (with implications for both nature and for us); and that “everything is connected.” In this world walkable mixed-use villages, towns and city neighborhoods are the primary ways human animals employ productive and practical reason to occupy the landscape well. If human beings are to live harmoniously in, with, and from nature, both frugally and abundantly, it will likely be in these physical forms of community. In such traditional settlements just and generous communities create economic, social, and spiritual capital, manage their adjacent landscapes well, make durable and beautiful buildings and locate the most important of them in places of honor. Such physical patterns elevate us, and Christians can begin to recover them today even in small parishes and congregations, and of course not only Christians. Any small community of any size can become part of a polis, that earthly “community of communities” Aristotle identified as the highest because it exists to promote human flourishing, the highest good human beings can achieve in this life – an estimation of the City of Man that even Augustine endorsed insofar as it promoted “the end [telos / finis] of earthly peace.”

But Augustine also knew what all Christians should also know: that our best earthly cities anticipate, and may even in some mysterious way participate in, that larger urban cosmic telos that is the City of God.

Coda:

[Granting]the principle of local loyalty, we are engaged in a search for the appropriate geographical unit . . . for a non-arbitrary alternative to the nation-state. Instead of looking more widely, I suggest, we should look nearer at home, to the “local” in a more restricted sense. The scholastic tradition of Christian political thought used to hold a doctrine . . . that decisions ought to be taken on as small a scale as was reasonable, it being the task of higher orders of government to afford “help” (subsidium) to lower orders, not to assume their responsibilities from them. There is no absolute way of defining what this reasonably small-scale unit of decision-making should be…. But we do have a notion . . . of a community which is self-sufficient [not] in the sense that it could isolate itself and do without mercantile and cultural interaction with other communities (for there is no community which could safely do that); but self-sufficient in the sense that its members can find within its bounds the resources they need for the pursuit of their lives: food, work, education, leisure, culture, and a land in which to move around and take delight. The scholastic understanding taught that the community which was, in this sense, self-sufficient or “perfect,” generated within itself its own political authority…. In the self-sufficient local community there is a resource of political authority waiting to be rediscovered; and the Christian church, which has striven to be both universal and local . . . is in a good position to point the way. Out of the service of the locality we may hope to see new political creativities released.

- Oliver O’Donovan, “The Loss of a Sense of Place,” (Bonds of Imperfection, 1989)

Philip Bess is Professor of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame.

NOTES:

[1] If, as I suspect, there are readers with a particular interest in the aesthetic import of Christian church architecture, I invite consideration of and (if desired) commentary upon the proposition that follows, my own further elucidation of which here would further surpass the assigned limits of this introductory essay (and also perhaps my competence). I presume however we will not recover a good culture of church buildings apart from recovering a good culture of building.

Christian houses of worship and their ancillary buildings and spaces are properly understood as communal statements of faith that invite both Christians and non-believers to acknowledge and worship God. When such buildings and spaces are beautiful, durable, and shape and ornament the public realm, they reinforce the faith of Christians, open the minds of non-believers to more sympathetic consideration of Christian truth claims, foreshadow the New Jerusalem as eschatological gift, and participate in the New Jerusalem as sacramental presence.

[2] The incoherence of contemporary architectural discourse in particular, manifested directly in the incoherence of our built environment, reflects the absence of any widely shared architectural-and-urban telos beyond the bottom line of developer spreadsheets, the life-safety criteria of modern building codes, and the off-street parking mandates of use-based zoning.

[3] If the late sociologist Peter Berger is correct, modern metaphysical uncertainty is caused less by advances in science than by the relativizing effects of cultural and religious pluralism characteristic of modern societies that make metaphysical certitude inherently more difficult. Sadly, Berger died before he could write a treatise on the social reality of construction.

[4] The cumulative effect is summarized in Bess’s Second Law of Architecture and Urbanism, which states that

A widespread desire for and expectation of social predictability from everyone else (a culture of bureaucracy), combined with a widespread desire for and expectation of maximum freedom for oneself (a culture of personal autonomy), will never produce a beautiful, coherent, and intelligible public realm.

[5] My not entirely unsympathetic view of Christian integralism is that it is properly regarded as an eschatological condition (certainly Catholic, but also catholic) rather than a plausible or human historical possibility at the scale of a modern, pluralistic, continental nation state. Until the eschaton however, in pluralistic societies, the American constitutional tradition of non-establishment / free exercise -- in which the state demurs from adjudicating religious truth claims owing to its lack of competence to do so -- still seems to me the best way so far for human beings to collectively acknowledge the sacred order in which creation itself is grounded while at the same time respecting the inherent dignity of human beings, our multiple religious traditions and communities, and the different ways in which human beings understand the individual and communal obligations that follow from our different understandings of God and the details of the sacred cosmos within which we exist.

-->