What follows isn’t just because of the last few days, but the last few days have helped.

The background is this: I’ve spent nearly the whole month of February in Venice, in a ground-floor apartment in Dorsoduro that I suspect used to house animals, based on its layout, but which has been nicely refitted with mod cons, including an induction stove which I took around an hour and a half to learn how to use and which still frightens me, and a washing machine that sort of washes clothes, and of course no dryer, which is a peculiarity of everywhere in Europe that I know of, but which in Venice is a perplexing problem in February, given the weather (somewhat chilly and extremely lagoon-adjacent.)

I stayed here with a friend over Carnevale (no it was NOT a vacation, I was WORKING, during the day), and then, after Lent began, when there was no possible chance that he might under any circumstances be invited to any party, my husband joined me, and we had a lovely co-working week in Venice, drinking Aperol spritzes in the lobby of the Danieli. He brought over my podcasting mic and his own and we happily generated content together in adjoining rooms in the former stable, and I made espresso in a Bialetti on the induction stove, and made various kinds of pasta, and then at night sometimes we would go to a concert or to a restaurant where they serve you eight kinds of fish paste unless you actively discourage them.

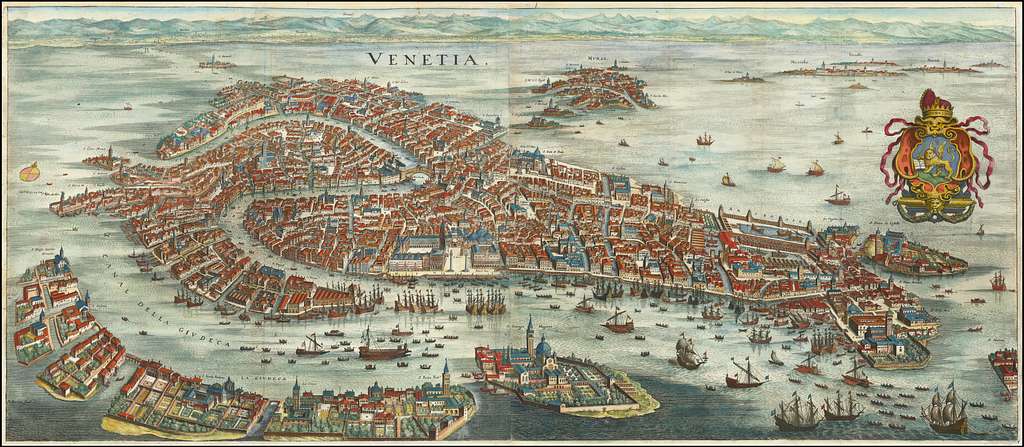

Venice is Venice: tiny narrow alleys and tiny arched bridges over canals of a variety of width. The city is made up of 121 islands, linked by 435 of these bridges, each slightly different, each a model of craftsmanship. The islands are in part man-made, a vision enacted over centuries, beginning with its founding in 421 AD by refugees fleeing Lombard invaders (or possibly, depending on who you talk to, 1500 years before that by refugees from Troy.) The refugees camped on the islands: my impression is that “islands” is a bit of an overstatement and that a lot of them originated as slightly less squashy patches of lagoon. These sons of Adam and daughters of Eve did their own subcreation here: they deepened channels of the lagoon into ordered canals, encouraging the water to flow there and drain away from the slightly higher areas, separating the water from the land; into these non-canal areas they drove (eventually) tens of thousands of oak trunks as piles; because the water drives out any oxygen, time does not rot this wood, but renders it into something like stone.

On those piles, they built their houses; the blocks of houses themselves are the islands, really. From wood to brick, to brick plastered and painted, to stone; from shacks to comfortable houses to palazzi.

Each palazzo has an internal courtyard; when you visit one at night on your way to a party, you pass quickly through half-seen internal spaces open to the sky, filled with marble statues or gardens, and very frequently building materials, for some repair job in process. Everything is always under construction, always needing to be raised and drained and reclaimed. Creation goes on continually here.

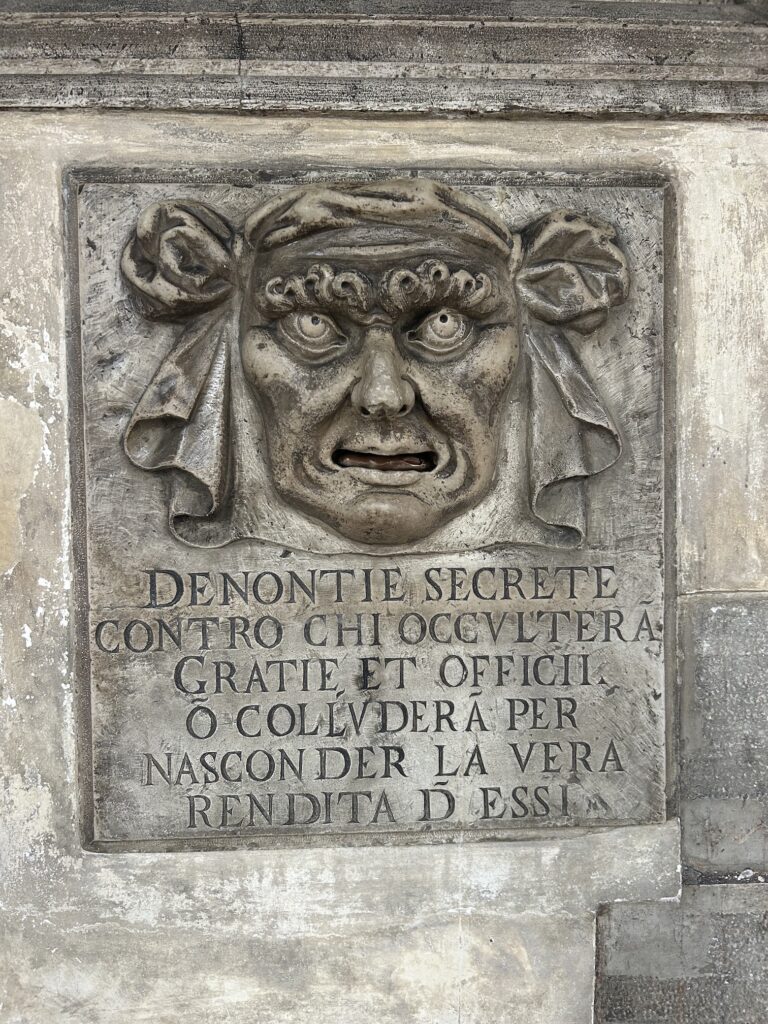

I suspect that those private courtyards probably make up the majority of the open space in the city. Venice is private, secret, as secret as the Bocca di Leone, the carved face set into the wall of the Doge’s palace, through the mouth of which any person could post a note denouncing his fellow-citizen of anything in which the state might be interested. The characteristic written thing, here, one feels, is that note of denunciation, or perhaps a privately circulated memoir, like those of Casanova. It is not a city that feels as though it has ever had much use for the newspaper, is how I would put it.

It is the interior rooms – primarily of the Palazzo Ducale, but also of the other palazzi – which are spacious and which feel like the places where the real business of the city is done. Its public life is private. The public piazzas are, comparatively, much smaller: each with its Aperol umbrella’d cafe geared towards aperitivo, prosecco, and evening.

And then of course San Marco. For open space one goes to the Piazza San Marco, and if you need more, you can walk out towards the two pillars, one topped by the Lion of St. Mark, the other with St. Tódaro, Theodore of Amasea, the city’s first protector, standing victorious over a dragon that looks very much like a crocodile. He was demoted when the relics of St. Mark the Evangelist came, on January 31, 828, to reside in the city.[1]

The pillars, then, commemorate a Greek-Syrian Roman legionary, martyred for his faith[2] in Turkey, and an apparently somewhat troublesome Jewish-Roman companion of Paul and Barnabas who, as the first Bishop of Alexandria, brought Christianity to Africa.

Between them, one sees the lagoon: the sea which is the real public space of the Venetian republic. It is always something of a relief, a rest, after the charming but maddening warren of narrow alleys and tiny bridges, of sottopotegi and fondamenti and fish-paste sandwiches.

We went to the Basilica itself, our last day there. It was absolutely bucketing down rain, the Piazza ankle deep in water in some places, and we ducked into it half for shelter. I had never been inside, though this was my third time in Venice, my third Carnevale.

Inside … inside it is golden. A world with a golden heavenly dome arching so high over your head it hardly seeems possible– no, it actually doesn’t seem possible at all. It is very clearly a model of the cosmos, aiming to be as intricate and detailed and rich as the cosmos itself, the millions and millions (surely?) of tiny quarter-inch golden mosaic tiles as gleaming and plentiful as the tiny fish that school in the lagoon. And under your feet are the bones of the Evangelist. John Mark: ̓Ιωάννης Μάρκος, the first name a good Jewish one meaning God is gracious; the second a Roman one, after the god of war. It is a Byzantine basilica, not a Roman Catholic church, in its architecture, though not in its confession. It is a reminder of the time before the schism of 1054 made us into Roman Catholics and Orthodox, and eventually Protestants, rather than just Christians.

But this is not a story about Venice.

On Saturday, when we woke, my jacket was still soggy, but the sun was gleaming on the canals, and as we headed to the Piazelle Roma with our luggage (I left my costumes behind in a giant duffel bag so we were traveling light, except for all the gifts and souveniers, and my husband was carrying those), it almost seemed a shame to leave.

And we almost didn’t. No one seemed to know where the bus to Ljubljana was leaving from, and indeed many of the people we spoke to denied that it existed at all.

“These are all local busses, as you see,” said the Venetian staffing the info desk, sharply.

“But… prego…” I showed her my ticket, mutely. Venezia Piazelle Roma, Italia, to Ljubljana, Slovenia. A somewhat confusing small-scale map of the bus station. She shrugged.

I ended up speaking with, or WhatsApping with, a total of ten persons: Italian, Slovenian, Croatian.

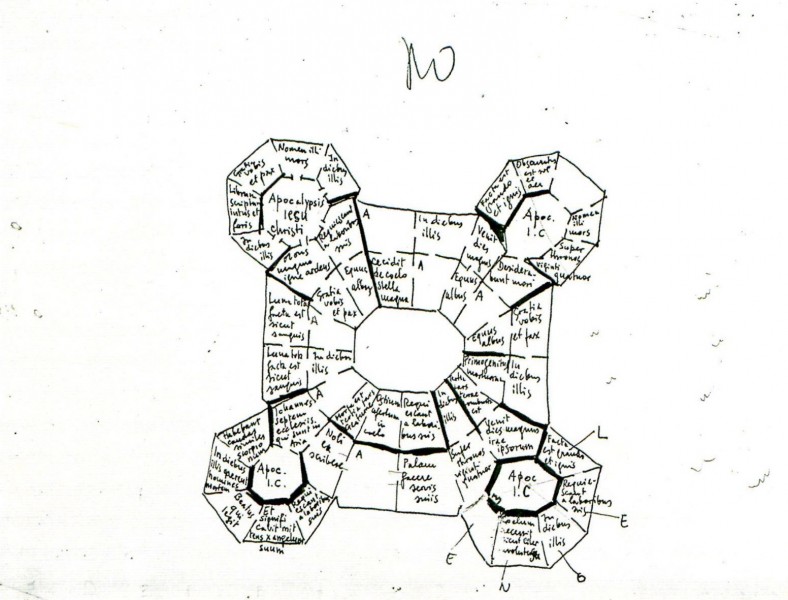

I came to be at peace with this. Clearly I had misunderstood the nature of the task before me. It was something like a quest, an Umberto Eco novel of transportation logistics. Each person I spoke to has one more piece of information. It was my job to diligently seek it out, following instincts, hints, sometimes rumors, fragments of text unveiled beneath a palimpsest, gnomic sayings by carabinieri. These I must synthesize; I must understand the underlying order, implicit, but always, tantelizingly, out of reach.

Eventually I spoke to a woman, Oleksandra, in North Macedonia, according to her WhatsApp. Unsettlingly, she seemed to to know who I was. “Susannah… yes… your driver says he will be late, by twenty minutes.” Something about one of the other passengers, and the police. She told me to stand near, but not in, bay B2. She suggested that we get a coffee.

Forty-five minutes after we were due to depart, as Alastair and I were lurking by a stone wall near, but not in, bay B2, nursing our coffees, a man approached. He was the driver. The bus was a van. It also was near, but not in, bay B2.

Three hours later, we were in Ljubljana.

It was my second time there. The first had been just before Covid, when on a whim I went there from Trieste in an attempt to track down Slavoj Zizek. I got his email from John Milbank, and sent him my phone number, suggesting we meet. I am not sure if I gave any pretext, aside from saying something about being a journalist passing through. He called. “Susannah… yes… I am very ill, very ill. We cannot meet. I am sick, so sick.” It was not Covid; it is all very unclear, though he was deeply courteous and apologetic. He sounded sick.

This time, we were meeting friends.

I love Venice.

But when we got out of the van in Ljubljana, I took a deep, deep breath. We walked towards the center of the city, through the green of Congress Square, with the buff-yellow painted Slovenian Philharmonic on one side, the main building of the University, the Ursuline Church of the Holy Trinity, a pavilion in its center, and came to Prešerin Square – cobblestoned, gracious, generous elbow room, its wide Triple Bridge across the Ljubljanica, the Franciscan Church of the Annunciation, Hauptmann House, the Galerija Emporium. Beyond, again in buff-yellow, Krisper House, where Gustav Mahler stayed in 1881-2, when he was the visiting conductor for the Philharmonic.

The facades of the most prominent buildings ranged from, I would suspect, 1700 to 1910. Baroque, Beaux Arts, Art Nouveau. Maybe? I don’t know these things, Phil does. They all, though, worked: the newer, larger fin de siecle stone buildings recognizeably more recent descendents of the older ones, with their painted plaster (I think) over brick (I think).

In the Grand Union Hotel (also the same buff-yellow color) is the Kavarna Union, its interior blessedly not modernized, or not really, though the old copper and brass capuccino and espresso machine has been replaced by a modern (though art deco looking) shiny red Julius Meinl one. (The old one has a place of honor where you can see it as you go to the loo, though.) Dark wood chairs with bent backs, dark wood curved coat racks, elaborately sculped plaster ceiling, a mural of a woman in a large hat, kaffee mit schlag, and apfelstrudel. The only thing that was missing, to be fully characteristic, was the newspapers on willow rods, arranged in a rack for customers’ convenience.

Characteristic of what, though? What was that sense I had in Ljubljana that I had not had in Venice? It was not a matter of Italy as against Slovenia. I have the Ljubljana-feeling in Trieste as well, though in no other Italian city. I had it yesterday in Varaždin, and today in Zagreb, where I have been writing this.

The clue is in the color of the public buildings: that buff-yellow, utterly distinct. It is called Schönbrunner gelb, Schönbrunn yellow. It is the color of the palace of the ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

It is the feeling of city that is a daughter of Vienna. It is the feeling of a Habsburg city.

When I walk around a Habsburg city, my sense of bonhomie grows to frightening levels. I become energetic and inventive, hard-working but also relaxed, safe. I feel such a powerful sense of wellbeing that it seems as though I might accidentally start a magazine.

I had known this feeling first in Vienna, when I first visited about fifteen years ago in the company of Frederic Mordon, who, at age twelve, left just in time to avoid the Anschluss. His name had been Felix Mandelbaum then, but I knew him as Fred, my dad’s friend and drinking companion at Elaine’s Restaurant in New York City. I used to go there every Thursday, nearly, from when I was twelve to when I went away to college, and hang out with that gang of journalists and screenwriters and novelists, and drink Shirley Temples.

Fred was a novelist; most importantly, though, he was a historian, a historian of his beloved Vienna. And he told me stories: the stories of an expat. Full of nostalgia for the Vienna of his childhood, a world full of gugelhupf and freshly-printed newspapers that smelled of ink. His family had not been particularly obeservant, and he was never very observant himself. He was a Jew, he was a writer, he was a New Yorker, but perhaps especially, he was Viennese.

When he invited me to go along with him to the premiere of the musical based on his book A Nervous Splendor, a history of Vienna in the years 1888-89, focusing on the death of Crown Prince Rudolf in the hunting lodge of Meyerling in the Vienna Woods, a suicide pact (possibly) with his seventeen year old mistress, Countess Mary Vetsera, I jumped at the chance. I loved his books, I loved Jack Murphy and Frank Wildhorn and Nan Knighton who had written the musical (and was chronically obsessed with their Jekyll and Hyde as I would be later with their Scarlet Pimpernel).

I loved Vienna from a distance: I had done some academic work on its coffeehouse culture, a major paper in preparation for my Master’s thesis, which was on the earlier coffeehouse culture of Dr. Johnson’s London. I’d called up Fred for bibliographical suggestions and fact-checking, while I was working on that, and he had happily obliged. He told me about the city’s coffeehouses: the Landtmann, near the university, where his parents had gone on their first date; the Hawelka, which doubled as the magazine offices of a political journal; and of course Café Central, haunt of Peter Altenberg, Theodore Herzl, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Robert Musil, Sigmund Freud, and Stefan Zweig. I loved all these things, and I loved Fred. So I went, and he showed me all those places in person.

The Central is the prototype, maybe, or at least the highest form of the type: a Viennese coffeehouse is palatial, ornate. There are chandeliers, polished brass, sculpted plaster ceilings, marble and glass and lots of dark wood. There are brass coat hooks next to the booths or tables, and tall dark curved-wood coat racks. There is a rack at the front where the day’s newspapers are ranged, each paper in a distinctive bent willow and beach holder.

There are a lot of newspapers.

There is an enormous steampunk looking brass and copper espresso and capuccino maker, but you don’t order an espresso: you order a kleiner Schwartzer or a großer Schwartzer (a single or double espresso), a kleiner or großer Brauner (same as the above but with a small jug of hot milk), a Verlängerter (an espresso with hot water; i.e. an Americano). If you are wise, you will order an einspanner (an espresso with whipped cream, aka Schlagobers or mit schlag), served in a glass, or a Kapuziner (a double espresso with MORE whipped cream, served in a cup). Or you could order a Wiener melange, which is more or less just a capuccino, though it’s complicated.

If you order a “mocha” they will think you want a Mokka, which is Turkish coffee, which they will bring you, with water on the side.

If you want a mocha, there is a drink you can order – at least in Ljubljana – which I just learned about which is a word that means I believe “Countess” (I forget what the word is in Slovenian, though.)

In the glass case at the front there will be pastries of all kinds: apfelstrudel, mille feulle, Marillenknödel, gugelhupf, and, of course, Sachertorte[3]. There will also, on the menu, be something called Kaiserschmarren, which means The Emperor’s Nonsense. This is a pile of shredded pancakes smeared with plum jam, and yes, they were Franz Josef’s favorites.

There are coffeehouses like this in every city in the Empire, all of them gesturing towards the Central in their menus and interior decoration, in their newspapers, in their political and literary arguments. They gesture towards the Central as the Schönbrunner yellow public buildings in all those cities gesture towards Schönbrunn itself.

These cities also share a set of other standard features. There is of course the castle above the city, Grad Something-or-Other, a relic of pre-Habsburg times. There are probably Roman ruins, with a nice museum. A Cathedral, other churches, including one or more Orthodox churches, a post office, a railway station, a grand hotel, an opera house, a philharmonic, a comedy theater, a central library, perhaps a university and a natural history museum and an art museum. Almost all of these buildings will be in some style between 1700’s Baroque and 1910’s Art Nouveau. Some of the coffeehouses will be modernized in their interiors in a faintly Art Deco direction. There will be statues of men on horseback with muttonchop whiskers; the further East you get the more likely they are to have curved swords and to have died fighting on the border with the Ottoman Empire.

They will not, probably, have a synagogue. They will instead, near the Jewish cemetary, which is well kept up, have a memorial.

But they used to have a synagogue.

“All architecture represents the power of its makers and their aspiration to legitimate authority,” wrote Philip Bess in his initial piece in this series.

By this I mean that the act of building has both practical and metaphysical implications. Building is a willful act of symbolic import, its symbolism sometimes intended and sometimes not, and never fixed; but all architecture expresses the power of its makers and their aspiration to legitimate authority. This is true not only of buildings but also public spaces, indeed of all human settlements. Their very existence presumes the power of human beings in the most elemental sense. More than this however, human beings attach moral significance to our buildings and landscapes. Legitimate authority is that moral “more than” mere power, more than the human capacity to will something and make it so. Legitimate authority is trustworthy power wed to moral virtue in service to shared communal ideals, a communal and metaphysical constraint upon and direction of human powers. In the realms of architecture and urbanism, aspiration to legitimate authority entails an ambition to unite beauty with goodness and truth.

The remainder of this essay will be an attempt to read. To read Vienna, and to read those Habsburg cities. What is the aspect of the good, the true and the beautiful, considered in architectural and urban-planning terms, that is expressed by those squares, those Baroque and Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts facades, and some Art Nouveau ones as well; those town halls from 1700 and opera houses from 1800 and those fin-de-siecle hotels and coffeehouses? What is the meaning?

The very brief version is this: this architecture, these traditions of plazas and buff-yellow civic buildings and coffeehouses with wrought-iron or wicker chairs and little tables that spill out into the plazas, say: Christ is Emperor. The Catholic Church is his kingdom on Earth. In the lands where He has given the Habsburgs sway, in an empire that is an earthly picture of his own, they are responsible for creating a common civic life for all the nations included in their empire. All nations – and all religions.

In the country, mostly, people will live alongside men and women of their own nation, their own religion. But here in these cities, Austrians will order coffee and read newspapers next to Hungarians, Slovenes next to Croats – and Protestants next to Catholics next to Orthodox, and Jews next to both.

And that too is part of a catholic vision of reality. If in the world to come, all (in the Habsburg view) will acknowledge Christ and know His Church to be the one founded on Peter and based in Rome, and thus religious diversity will give way, still, also in the world to come, national diversity will not – not precisely. Nations will exist and bring their riches to His imperial court – and, in the coffeehouses of the New Jerusalem, will mix and befriend each other, will live alongside each other and share a common civic life.

If that is what will happen in the New Jerusalem, reason the Habsburgs, then that is what we will imitate here, in Vienna and across these realms.

It is good for nations to exist. But it is not necessary for nationals to live separately, to have separate civic realms, to avoid collegial friendship – or marriage.

The empire, in other words, is a rebuke to the ethnostate. The imperial city is a glorious political unity that provides a comfortable and inviting civic realm for genuine national diversity. In the coffeehouses of Vienna, and Ljubljana, and Varaždin, and Zagreb, this world was lived out.

Franz Josef and Franz Ferdinand consciously promoted this vision: open borders between the different national areas of their empire was a crucial policy. Franz Ferdinand was, if anything, even more dedicated to this vision than his imperial uncle. He had travelled to America, and saw there both ethnic diversity and a federal – but unified – system of government that presented itself as obviously intriguing. In his accession speech – the speech he never gave – he wrote:

We desire to treat with equal love all the peoples of the monarchy, all classes and all officially recognized religious faiths. High or low, poor or rich, all shall be held in the same before the throne. … Just as all people under Our scepter shall have equal rights of participation in the common affairs of the monarchy, equality requires that each of them be guaranteed its national development within the framework of the monarchy’s common interest, and all nationalities, all classes, all occupations shall, where this is not yet done, be enabled by just electoral laws to protect their interests.

And when he married, he married not some Bavarian princess but the Bohemian Countess Sophie Chotek.

It was their way. Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube – “Let others wage war: thou, happy Austria, marry”. That was the slogan. And it was surprisingly accurate. For six hundred years, the Habsburgs had extended their empire not by the sword, but in the marriage bed. Franz Ferdinand’s imperial and royal relatives were (to say the least) not happy with his love-match, but certainly not because she was a Slav: rather, because she was only a countess, not of royal blood; she was not even rich, and had in fact had to take a job as a paid companion to Franz Ferdinand’s aunt, which is where he met her. They fell deeply in love and stayed that way, and had three children. But she certainly brought no new lands to the empire.

But many other brides had. The result of this Habsburg expansion-by-marriage strategy was an empire made up of twelve distinct nationalities, hundreds of ethnic groups, and many religious traditions, not all of them Christian. Franz Joseph’s fifty million subjects – imperial citizens – made up the most diverse empire on earth.

And very self consciously one that had a Christian mission and identity precisely as that empire: catholic, as the church is catholic. In Linz, in Upper Austria, just after the turn of the century, Fr. Franz Sales Schwartz would lecture his pupils: “In your heart you should have ideals for our beloved country, our beloved house of Habsburg. Whoever does not love the Imperial Family does not love the Church, and whoever does not love the Church, does not love God.”

This was perhaps overkill. But it was representative, and many, many people believed it: call it a relaxed imperial Catholic integralism, mit schlag. And it was – even for those who didn’t share that spiritual vision – deeply loved.

That was the strange thing. It was not only the Catholics who loved this empire and its grandfatherly head: Jews, in my own experience (this isn’t just about Fred), look back on this time – from perhaps 1867 to 1914 – as a kind of golden age, shimmering in memory, a cozy bourgeois world of childhood and snowy winters and trips to the Prater in the spring as a special treat: a time when the promise of emancipation had come to fruition. They were doctors, lawyers, university professors. They were Jewish. They were citizens. They were Europeans. And they were, with deep affection and joy, imperial subjects. They loved their Emperor, their “angel,” their “protector,” and they loved his world.

Of course it was not perfect. Of course there is the glow of nostalgia, that instagram filter of history, which colors things. But we have to ask ourselves: What is the good version of a thing? The good version of a thing, and not its corruption, is the reality of that thing. This addiction to the “dark underside” being more real is absurd. Freud perhaps would say that the truth of the Habsburgs was in Crownprince Rudolf’s adultery and suicide, or Sisi’s anorexia and hysteria, or Sophie’s snubbing by her husband’s family. But that is not so.

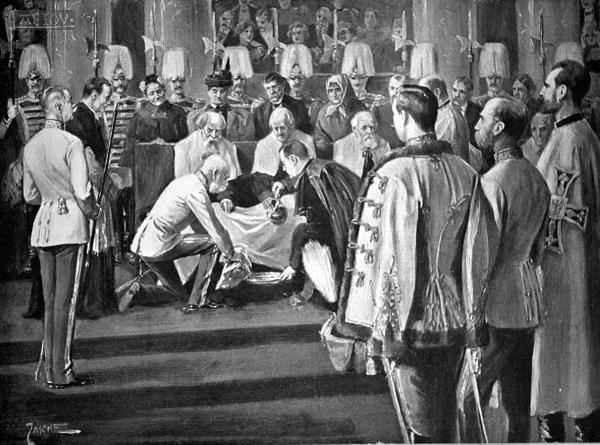

The truth of the Habsburgs is in their myth: in the idea of an empire built not by war but by the marriages of a family, built on faith in Christ. Franz Josef washing the feet of twelve paupers, every Maundy Thursday. The fact that, on the death of each emperor, when the corpse was brought to the Capuchin crypt that held all the family tombs, the Grand Chamberlain would knock.

A friar would ask, “Who is it?”

The Chamberlain, speaking on behalf of the corpse, would say “I am Franz Joseph, Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria, of Illyria, and King of Jerusalem, Archduke of Austria, Grand Duke of Tuscany and Cracow, Duke of Lorraine, Margrave of Moravia, Duke of Upper Silesia, Lower Silesia, of Modena, Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, Prince of Conde-Hapsburg and Tyrol, of Kyburg, in Goritz and Gradisca, Prince of Trent and Brixen, Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia and Istria, Earl of Hohenembs of Feldkirch of Brigance, in Sonnenberg, Lord of Trieste, of Cattaro and Marche, Great Voivode of Serbia,” and so on.

The door would not open. The Capuchin would reply, “I do not know you.”

Again, the Chamberlain would knock, and again the friar would ask, “Who is there?”

“I am Franz Joseph, His Majesty the Emperor and the King.”

The door stayed closed. “I do not know you.”

A third knock.

“Who’s there?”

“I am Franz Joseph, a poor mortal, and a sinner.”

And the door would open.

That is the truth of the Empire.

And so is all those bourgeois fathers taking coffee in those cafes, buying perhaps a new novel, or a new book of poetry, just printed, or in December ducking into one of the stores on Mariahilferstrasse out of the snow, stopping on the way home for one more present to bring back to put under the tree: a wooden top. A richly-illustrated book of faerie tales. Some new sheet music. A nutcracker, shaped like a soldier.

And so is Franz Ferdinand’s marriage to Sophie. It was extraordinarily popular, including in America. Sophie was a deeply religious woman, loyal wife, and loving mother of three of Franz Ferdinand’s children. She wasn’t a philosophical pacifist, but she was, so to speak, a dove. Her dear American friend Maria Longworth Storrer wrote: “Franz Ferdinand was captivated not only by her unusual beauty, but by her brilliant mind, and by the Christian zeal and integrity of her character.” She was beloved. Her world was beloved.

But not everyone loved this world. One of Fr. Schwartz’s pupils later recalled laughing at his words; the priest told his mother that he was a “lost soul.” That pupil, Adolph Hitler, preferred the teaching of his rabidly anti-Habsburg high school history teacher, Dr. Leonard Pötsch, who ranted about the corruption of the Habsburgs and their multinational empire, the disgusting fact of Slavs being treated as citizens alongside Germans. And even marrying the heir. Hitler hated Slavs long before he hated Jews: it was so to speak his apprenticeship hatred. By Pötsch’s – and Hitler’s – account, Sophie was practically subhuman, one of the Üntermenschen. The imperial family was, once again, mixing its already-questionable blood with that of lesser races.

Pötsch, and his protegè, hated everything about this. Territory should be won by Prussian swords, not Austrian lovemaking. And the subjects of a Prussian, a German, empire must be kept rigidly separate from their rulers – not made citizens and certainly not married. Pötsch spoke passionately of the need for a German national revolution to purify the race. “His dazzling eloquence not only held us spellbound but actually carried us away,” wrote his most famous student years later. “We sat there, often aflame with enthusiasm, and sometimes even moved to tears… it was then that I became a little revolutionary.”

His roommate in Vienna (and only friend) remembered that “his fury turned against the state itself, this patchwork of ten to twelve, or only God knows how many nations this monster of Habsburg marriages built up.” It was Habsburg Vienna, the “Babylon of races,” that convinced Hitler that only blood, only a war, a revolution, something, could save German Austria from a tide of immigration and assimilation: the mongrelization represented precisely by Franz Ferdinand’s marriage to Sophie. When Hitler heard about the assassination of the couple on June 28, 1914, he wept with happiness: now there would be war.

Was it inevitable? There’s a tradition of course that says Yes. This tradition, Marxist in origin, argues that imperialism structurally required the war to happen. Big things like that don’t happen because of human actions, Great Men, let alone little ones like Gavrilo Princip.

I do not share that philosophy of history (though, having recently re-read War and Peace, I have just drenched myself in Tolstoy’s warmed-over Hegelianism that resembles it). Therefore one can ask about the specific event: was this big event inevitable, even if not all are?

Many, many historians, and very recently and readably the journalist Matthew Yglesias have argued, to my mind persuasively, that it was not. 1914 was, in Robert Nozick’s words, a time of thin causality. Other times are not: Romney and not Obama gets elected, and four years later we probably still have a financial crisis. But that time, in Sarajevo: that time, history turned on a dime. Yglesias has developed this argument, and the vision of the alternate 20th century that would have played out, here.

Not everywhere should be a Habsburg imperial city. Venice is distinctly not: it is itself, its gelato a far cry from sachertorte, its main dishes all tasting faintly of the lagoon. It is wonderful, I love it deeply, it is a vision of republican rather than imperial or monarchical order which is refreshing, but it was also a closed society, closed not just to non-Italians but for the most part to non-Venetians.

In that respect, it failed to picture the New Jerusalem in the way that Vienna did, though surely it pictured it in other ways: this city that was formed by spirit, by the Winged Lion, bringing the Word of God, his wings beating as he flew from Alexandria, stirring the face of the water and bringing forth dry land.

Each place, before the Parousia, is a partial image only of that Empire of Christ, that Kingdom. Of course all can be criticized, all are imperfect, all still fallen, all still tainted by the tincture of sin.

But see the good: Here we see a small Appalachian or Bavarian town bound with local love, its few families intermarried for generations, their names on the graves in the churchyard. Here we see a city-state conducting business characteristically by peaceful trade rather than pillage. Here we see a nation, born of Britain and modeling itself on Rome, dedicated to the freedom of its citizens, anchoring their rights not in its gift nor ultimately even in their heritage from their island home, but in their creation by the Divine Architect of the World, welcoming the tired, the poor, the huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

And here we see an empire which has grown not primarily by conquest, but by marriage: Vienna, and its Empire, is one – one of many, yes – that speaks to my heart. It was, for a time, and imperfectly, a world that brought heaven to earth, as is the job of each Christian man and woman, and of civic religion.

Because in the New Jerusalem, men of all nations will befriend each other, swap newspapers, form Althusian collegia, design buildings, edit magazines, make projects and plans, drink coffee mit schlag and eat apfelstrudel, invent desserts even better than Sachertorte for dignitaries even more glorious than Metternich, and get on with the good bustling human work of the Empire of the Prince of Peace.

Susannah Black Roberts is the Senior Editor of Plough Quarterly.

[1] Short story: they had been in Alexandria, but the Ottomans were closing in, and some enterprising and city-proud Venetians who happened to be there took the opportunity to rescue them back to the lagoon. The whole process, notes the Basilica’s website with somewhat atypical understatement, was “not without adventure.”

[2] This is complicated. He is widely described as a martyr, killed in 306 under the Emperors Galerius Maimian and Maximian, but if you look him up in the Catholic Encyclopedia, you are told that “He enlisted in the army and was sent with his cohort to winter quarters in Pontus. When the edict against the Christians was issued by the emperors, he was brought before the Court at Amasea and asked to offer sacrifice to the gods. Theodore, however, denied their existence and made a noble profession of his belief in the Divinity of Jesus Christ. The judges, pretending pity for his youth, gave him time for reflection. This he employed in burning the Temple of Cybele. He was again taken prisoner, and after many cruel torments was burned at the stake.” My feeling is, good on him, but “martyred for his faith” is perhaps generous.

[3] In 1832, Prinz Klemens von Metternich was visiting Count Esterhazy, in his house in Pressburg, now Bratislava, the capitol of Slovakia. He had invited – imposing rather on the Count’s hospitality, in my opinion – a set of guests of his own for a particularly important evening of negotiation and politicking. He asked Esterhazy’s chef to make some sort of special dessert for the occasion. The assistant to the chef, a 16 year old boy called Franz Sacher, let the Prince know that the chef was sick, but that he would take care of it. Eyeing the youth, Metternich emphasized the importance of the evening, of the guests, of the task. “Ich will mich heute Abend nicht schämen!” he is reported to have said. “Let there be no shame on me tonight!”

With that Princely exhortation as inspiration, young Franz came up with a dense chocolate cake, in two layers, with a thin layer of apricot jam between them, enveloped in chocolate ganache. The Sachertorte was born.

He moved to Budapest, and then, after the nationalist uprisings of 1848, moved again (wisely, one feels) to Vienna, where, some years later, his son, planning to go into the family pastry business, apprenticed at Cafe Demel, one of the newly-opened elaborate Viennese Cafes, where he refined his father’s recipe.

Eduard felt that pastry alone, though a very good thing, did not give full scope to his ambitions. He opened an inn, and then, after the opening of the Vienna State Opera (first performance, in 1869: Don Giovanni), decided to build a hotel opposite it. The architect Wilhelm Frankl, a Jew and a Viennese architectural superstar, was chosen, and he did not disappoint: the Baroque magnificence of the place is unsurpassed. It opened in 1876 as the Hôtel de l’Opera, but Sacher renamed it after himself in the 1890s. The restaurant offers small private areas, chambres séparées, the better to flirt and scheme.

In 1880 Eduard married the 21 year old Anna Fuchs. He died young-ish, and in 1892, Anna took over running the hotel. Anna, who smoked cigars and went nowhere without her French bulldogs, was also a regular customer at the Cafe Central. She had been introduced to cigars by the Hungarian Nikolaus von Szemere, a friend of Franz Ferdinand, who whenever he was visiting, politely refused the Imperial and Royal hospitality at the Belvedere because he thought the food was better at the Sacher. And so Franz Ferdinand used to come to the hotel to meet him there. He asked von Szemere not to tell Sophie, who would be insulted.

In 1907, Prime Minister von Koerber and Koloman von Szell, in one of those useful chambres séparées, successfully negotiated an adjustment to the political union between Austria and Hungary.

But it was in 1934, three years after Anna’s death, that things got ugly. Demel’s began selling something they called “Eduard Sacher-torte.” The resulting lawsuit went on through the war and did not conclude until 1965, when Demel’s was permitted to sell it as “Demel’s Sachertorte,” with it stipulated that they must stick to one layer of apricot jam between the chocolate cake rounds, and the Sacher was given the rights in perpetuity to sell “The Original Sacher-torte”, with two layers of apricot jam and a seal of authenticity, in chocolate, on each cake.