Nothing more aptly expresses the uncertain place of poetry in the modern age than American poet Ezra Pound’s pronouncement, in his ABC of Readings, that “Literature is news that STAYS news.” His old friend, William Carlos Williams, would faintly echo the thought, in “Asphodel, that Greeny Flower,” two decades later, when he wrote,

Both Pound and Williams want, clearly enough, to attach poetry to the news by some means, in the middle of that century during which, as Albert Camus wrote, modern man “fornicated and read newspapers.” Poetry has always occupied an uncertain place in our civilization, but the cause of that has varied from time to time. And, though the newspaper is a quintessentially modern thing—cheap, mass-produced, suitable only for an age where literacy is widespread, boredom yawning wide, and information both freely-dispensed and super-abundant—the news serves as a figure not only for the modern age but a whole host of other aspects of our civilization, some of them ancient.

It may seem one thing for a poet trying to sell his wares and another to puzzle over the purpose of human life. It may seem one thing to make claims upon a poem’s “newsworthiness” or, as Williams does, to insist that there is something in poetry that human beings need—mortal stakes—that cannot be found in the news, and another to ponder the nature of knowledge and of the human person as a knower; one thing to talk about literary value or permanence and another to speculate on aspirations of the soul to immortality, but, indeed, the questions are closely connected.

It is not news that human beings are entirely sunk down in the fluctuations of being, what Plato called the realm of becoming, such that everything on which our eyes fall is always swiftly passing away. Diotima tells Socrates as much in the Symposium, reminding him,

Even while each living thing is said to be alive and to be the same—as a person is said to be the same from childhood till he turns into an old man—even then he never consists of the same things, though he is called the same, but he is always being renewed and in other respects passing away, in his hair and flesh and bones and blood and his entire body. And it’s not just in his body, but in his soul, too, for none of his manners, customs, opinions, desires, pleasures, pains, or fears ever remain the same, but some are coming to be in him while others are passing away. (Symposium 207d-e)

The enduring question is whether anything survives or stands apart from this passage of evanescence. Diotima proceeds to show Socrates that everything that matters stands apart from the fleeting becoming of things.

The peculiarly modern question is whether what might survive it is of any value, or if the knowledge of swiftly passing things is all that we require, is fuel for the bonfire of reality, and so the very basis for anything’s demand on our attention. News is the speech that passes, such that nothing is so old as yesterday’s newspaper. And yet it seems as if our every glance over the newsprint running before us already and immediately calls out for something more lasting, something permanent.

When Pound and Williams appeal to the news in talking about poetry, they acknowledge that craving for permanence even as they put in doubt its reality. They want to justify being in terms of becoming, the stable in terms of the flux, because they, like us, know the flux already—they are sunk down deep within it—and are not entirely sure it will be possible to argue their way out of it the way Diotima did so confidently before Socrates, millennia ago.

Pound’s Fish Heads Wrapped in Newspaper

Pound and Williams were part of the first generation of poets to compose upon the typewriter. Their poems first appeared—not in publication, I mean, but for the very first time before their eyes, in the privacy of their rooms—already under the guise of newsprint, that is to say, as type. Their fellow poet, T.S. Eliot, wrote directly of the effect of the typewriter on his work of composition—it led to brevity and clarity, we may be surprised to hear, rather than to length and elaboration. The machine as machine took the private thought out of the realm of overflowing sentiment and gave it the austere clarity of thought. Type, for Eliot, was chastening and austere.

Pound’s commentary on the effect of writing in type can be gleaned from his extra use of spaces and periods between words, in poems and prose alike, as if the machine itself could impress a weighty pause. His prose is so wholly dependent on the expressivity of newsprint that much of what he communicates he does by isolating lines in the middle of a page, letting paragraphs appear as torn fragments from a page, and having emphases announce themselves by words in all capitals. Pound’s hammering both blank spaces and majuscules with typewriter keys echo the ancient practice of the epigram, the short poem that takes its name from having been carved in stone: type itself seems to make the poem at once more contemporary, like newspaper headlines, but also more lasting, because it is a mechanical production rather than a mere manuscript.

So also, in Williams’s case, the lines we quoted above, with their three-line steps, seem to have come about by a strictly technological necessity: Williams’ eyes were failing with old age, and typing the lines out that way made it easier for him to read (a verse form for “a blind old man”). The result is a text that, on the one hand, must have seemed stamped—made permanent, published—simply because it first appeared as type rather than script, but which also resembles the endless eruption and superannuation of strings of tickertape at the stock exchange. Decades later, the poet A.R. Ammons would outdo Williams in the use of exogenous technology as a substitute for technique intrinsic to the art by composing a long poem on tickertape. In all of this, the typewriter as personal newspaper press seems to have given the poets, at once, a heady feeling of flirting with the really evanescent, but up-to-date, of technology and also the seeming ever-lasting permanence of printed books in the library.

For Pound, the news involved much more than a literal fixation on the technology behind, to use our familiar synecdoche for newspaper journalism, “the press.” The news implied a whole way of thinking about knowledge. In The ABC of Reading, be begins by complaining of the “European” propensity to move from the perception of the concrete individual by way of abstraction to the universal idea. “If you ask him what red is, he says it is a ‘colour.’” Against this, he offers us a version of the famous story of the Swiss-American naturalist Louis Agassiz and the fish. As the story goes, an applicant to study with Agassiz comes for an interview. Agassiz brings out a fish preserved in a jar with “yellow alcohol” from his supply of samples, and asks the student what it is. “That’s only a sunfish,” the student replies, in Pound’s telling. That is not good enough. The student is left alone with the sample for days to study it, to perceive it in all its particularities, and, eventually to write “a four-page essay” on it.

Modern science, for Pound, does not seem to be the process of empirco-mathematical abstraction and mechanistic reduction that it is normally taken to be. That is, modern science does not continue the “European” proclivity for abstraction, simply redirecting its concern from unconditioned truths to physical laws subject to our manipulation, as Descartes and Hobbes had proposed. Science is about patient observation of the concrete particular.

In Pound’s telling, an important detail of the anecdote is changed: “At the end of three weeks the fish was in advanced state of decomposition, but the student knew something about it.” The fish is not preserved, but rather rots before the eyes of the disciple. Pound is so averse to abstraction that he wants the thing under observation to show us nothing lasts; abstract reasoning is a kind of pickling of ideas and Pound wants no part of it. Knowledge is attained not by way of making universal observations that transcend the individual at hand, but rather, in the transference of the particular thing decaying before us into the no less particular thing that is the “four-page essay,” the text in print. The second half of the ABC of Reading consists mostly of individual samples—poems from the tradition—that made an original contribution to the development of poetry. Pound reluctantly offers commentary so that we see the innovations, but he would rather allow the scraps to show themselves by themselves just like the sunfish on the laboratory table.

For Pound, knowledge is attained by way of biological science, but science itself has been reformulated so that it is more akin to the news in the papers. It is not universal laws we learn there, but particulars: a thousand rotting fish heads. In the span of his poetry, this occurs in roughly three ways. His early lyrics consist of fragmentary moments of dramatic monologues. They are like the poem of Robert Browning, but with everything but the emotional climax lopped away; or so he described them to Williams, in an early letter (1908):

To me the short so-called dramatic lyric . . . is the poetic part of a drama the rest of which (to me the prose part) is left to the reader’s imagination . . . I catch the character I happen to be interested in at the moment he interests me, usually a moment of song, self-analysis, or sudden understanding or revelation.

The result, to mix metaphors, is a somewhat constipated production as hard as a kidney stone. Such news stays news, because all the prosaic details have been allowed to pass away indeed and all that is left is the concentrated moment of emotion—which emotion is justified only by hint or suggestion of its cause.

Pound never lost his attachment to Browning and, to the end, his poetic sensibility remained almost entirely the product of the Victorians. But he felt badly about that, and tried to escape it. During the years of the First World War, he came under the influence of the English art-critic and occasional poet, T.E. Hulme. Hulme wrote a great deal while a young man, and then was killed in the War; his mind was still in an early stage of growth and it would be too much to expect his ideas all to make sense together. What Hulme is best known for is his account of modernist abstraction in the visual arts as a way of representing eternal mathematical and religious truths, the permanent, so that it shocks us and makes us conscious of our own pitiable evanescence as biological and emotional creatures. Every cubist hunk of stone was an up-to-date death’s-head for the machine age, stirring us to recall our mortality and to seek that which is above.

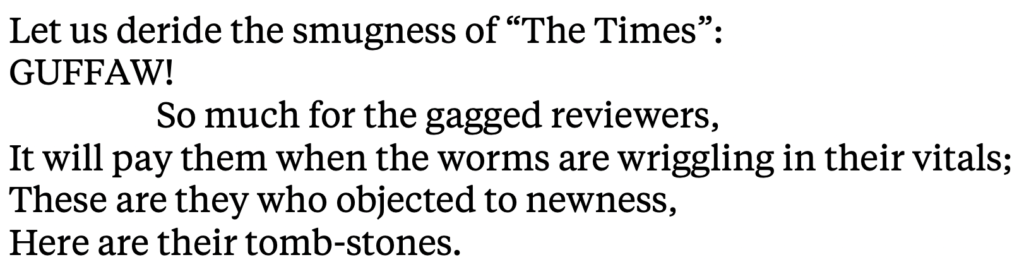

Hulme’s handful of poems look like roughly chiseled epigrams of stone, and so would seem to identify poetry with the eternal rather than the temporal. But, in fact, when he speculated about poetry, Hulme equated it to the leaflet or the newspaper. “I am of course in favor of the complete destruction of all verse more than twenty years old,” Hulme wrote, advocating the short, free-verse poem as something to be written quickly, distributed and read, and then left in the bin, so that a new generation’s work could come into being, totally unincumbered by the past. Pound would write many poems that indeed look like short news stories, or letters to the papers, their rhythms crude, their language colloquial and unmemorable, as in “Salutation the Third,”

Later, Pound would explore a different intermingling of poetry, science, and newspapers, in his Cantos. While there is much warmed-over Victorian lyricism in that poem, and such passages, in fact, account for almost all its memorable lines, the greater bulk of it consists of unreadable or barely readable passages meant to serve as what Pound called “luminous details.” Such details were particular items no less individuated than Agassiz’s fish, but in whom one could find “incarnated,” as it were, the gestalt of an entire historical age. Such details are not intended to function as symbols, which unite the universal and the particular as Christ joins human and divine natures, but rather like points on a map that hint at the map as a whole—or, rather, as a “periplum”

Periplum, not as land looks on a map

But as sea bord seen by men sailing. (Cantos LIX)

News stays news not by finding distilled or abstracted, timeless expression, but by the concrete detail conveying our subjective experience of “sailing” through the whole of history. This becomes clear in the ABC of Reading, where the chief “innovation” Pound celebrates is the movement of poetry away from “Popean comment,” by which he means abstract and witty sentences, toward “conveying information.” That by “literature” Pound refers to poetry more than to prose is also made clear early in that book, when Pound contrasts the “Homeric poems,” which one reads again and again, with detective stories, which one only gives a second reading if one read carelessly the first time and has forgotten the ending.

The Cantos makes for unpleasant reading, even as, like so much modernist literature, it continues to attract scholars just because there are so many points to “map,” that is to say, to annotate. In doing so, scholars get to participate in the scientific endeavor as Pound understood it; observing all that lies hidden within the inevitably inadequately “luminous” detail. Poetry itself annotates or maps the news, providing us an account of the whole of historical reality without ever leaving the plane of that reality. We see that the cumulative effect of Pound’s entire career in poetry was just an accumulation: particular images, particular snatches of speech or sound, particular historical innovations, meant to resist abstraction and to substitute for abstract knowledge’s natural role in giving us a sense of the whole.

Williams’s Pressed Flowers

Williams’s work, in its own day and ours, has often been described as “anti-poetry.” The Irish poet Denis Devlin once wrote of him that he “threw out all the literary luggage” and yet “continues to stand peering, in a mixture of rage and uncertainty, over the threshold of poetry.” Williams’s condemnation of poetic form, refined speech, and (somewhat inconsistently) allusion to the literary tradition were lost with the suitcases. The result was a poetry as committed to the particular detail as Pound’s but also committed to eschewing all poetic diction as un-American.

Sometimes his poems genuinely seem to aspire to give us the news, as in the early “At the Ball Game,” which celebrates mass culture while also remarking the threat of mass man to lash out in mob violence (of the crowd in the stands, he writes, “This is / the power of their faces”). “Asphodel” is a love poem to his wife; he first compares the poem itself to a book he kept with pressed flowers that “retained / something of their sweetness / a long time,” but as the poem continues, it admits into itself the “flower” of the nuclear bomb, the threat of nuclear war, which is always in the news and sickens everyone with its incessance. The result is poetry that gives us old news—conventional themes of love and lust—in the language of the newspapers, to be written and read quickly and not always thoughtfully. If news travels fast, Williams does not aim for something slower or more stable, but merely hastens to keep up. The “odor” of petals fades and the spectacle of the bomb confronts us in every headline.

The irony of Williams and Pound’s efforts to justify poetry in terms of the news is that, up until their time, poetry had played its part in helping us get the news. Oral street ballads, printed poetry broadsides, and newspaper verse were common enough ways of sharing information up until their day. Pound and Williams sought to remake American poetry specifically by rejecting such popular predecessors as the Fireside poets, especially Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. But Longfellow’s “Poems on Slavery” were propaganda that served roughly the purpose of a newspaper editorial and worked to significant effect in changing northern attitudes to the peculiar institution. Moreover, his “Paul Revere’s Ride” is still the way in which many American children first learn of the battle of Lexington and Concord. Longfellow’s poetry is always memorable but often stereotyped. In this it resembles a news story much more closely than any of Pound’s luminous details. Further, when we read it, we can name “what is found there” more easily than we can in reading Williams’s work: the poetic luggage is there, of meter and rhyme, incantatory phrasing that is easy to recite aloud and hear as musical, to retain and perform again.

It’s All Old News

Why Pound and Williams should have framed their understanding of poetry in terms of the news is not hard to discern. From what I have observed already, we see that it conjured up associations with the new technology of the typewriter; with concrete scraps of information rather than with abstract and universal generalization; with one—eccentric!—account of the modern sciences and scientific progress; and, through Hulme, with the ephemeral publications of the modern city—leaflets, advertisements—that are the equipment serving the habits of modern mass culture’s marketing campaigns, fast fashions, and continuous consumption. This left Pound in the odd position of advocating poetry as news that stays news even as his account of literary history was one that emphasized the need for constant innovation and experiment; permanence had a vexed, probably incoherent, position in his view of things, but he could not let go of it altogether.

We gain a better understanding of the uncertain, often contradictory, ideas of Pound and Williams if we simply look back to earlier moments in literary history where poetry and the news were in one way of another brought into tension. I will mention just three, with reference to John Dryden, William Wordsworth, and Aristotle.

In Dryden’s Socratic dialogue, “Essay on Dramatic Poesy” (1668), the persona Crites, in his defense of the ancient drama against that of the moderns, observes that the ancients, in a short span, developed the art to mature perfection. Our age has its own proper “genius,” but it excels not in the arts but rather in the sciences. The “virtuosi” of Christendom have conducted so many “useful experiments in philosophy” as to have “revealed to us” “almost a new nature.” Crites’s aim is to vindicate the supposed “Three Unities” of Aristotle and affirm the deference to them exhibited by the playwrights of the time. Dryden’s other personae prove game in showing that the Augustan style indeed displays a progress that, while imitative of the ancients, in many ways is also innovative.

But, as Timothy Steele observes in Missing Measures (1990), Dryden’s dialogue is one of the first modern texts to exhibit anxiety that poetry may be permanently stalled, even if stalled only because perfectly achieved, while the new sciences proceed apace to unbounded progress. Steele argues that the abandonment of rhyme and especially meter in the age of Pound and Williams came, in part, as a response to this mounting anxiety. If poetry was to participate in the modern age, it must exhibit at least some analogue of experiment, innovation, and progress. The alternative was not permanent achievement but stagnation.

Pound aligns poetry and science alike with the news as media to “convey information” regarding “luminous details,” that remain always in the concrete and in the continuous rush of the news cycle. The news never ascends from its bits of fact to a universal or abstract law. News that stays news is not the equivalent of permanence but of the continuous repetition of a singular experience somehow kept fresh. Such an understanding of poetry as news is suggested by Pound’s response to Matthew Arnold’s definition of poetry as a criticism of life: “‘Poetry is about as much a ‘criticism of life’ as red-hot iron is a criticism of fire.”

In allying the role of the poet with Agassiz, Pound rightly captures the way in which the object of poetry is at least as much our concrete experience of the truth as the universal truth itself. It has a responsibility to pay attention and to see clearly. But doing so is a matter of being thoughtful, and thoughtfulness ought to culminate—every so often—in the achievement of some actual thought. Pound tried to resist that conclusion, first, by misinterpreting science as somehow less dependent on abstraction than such other endeavors as philosophy and theology and, second, by equating its “information” with the perpetual novelty of the spread of particulars to be found in newspapers.

Writing a century before Pound, William Wordsworth, in his “Preface to the Lyrical Ballads,”thought the enduring role of poetry to be almost the antithesis of what Pound would argue. In a manner akin to Pound, he holds that poetry is “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” and so entails a direct immersion in the stream of experience that, for Pound, is summed up by the “news.” But poetry is also “emotion recollected in tranquility”; it is the product of mature philosophical reflection so that the immediacy of sensuous experience is deepened, completed, and stabilized in the steady gaze of wisdom.

Wordsworth was writing in the wake of the French Revolution, the first major political event to befall the modern age as a consequence of the rise of urban life and its saturation in cheaply-printed opinion and discussion. Wordsworth laments that modern persons, especially in the cities, are subjected to “gross and violent stimulants”:

For a multitude of causes, unknown to former times, are now acting with a combined force to blunt the discriminating powers of the mind, and unfitting it for all voluntary exertion to reduce it to a state of almost savage torpor. The most effective of these causes are the great national events which are daily taking place, and the encreasing accumulation of men in cities, where the uniformity of their occupations produces a craving for extraordinary incident, which the rapid communication of intelligence hourly gratifies.

Information assails the mind, brutalizes it, and makes it the instrument of revolutionary passions. The poet serves to recall us to ourselves, to call us away from the cry of news in the street, to a more natural place (indeed, to Nature herself), a place in keeping with our human natures, wherein we can recollect our true selves.

The poet’s attentions are philosophical rather than scientific. Rather than seeking to discover truths that one would not even have suspected, were it not for the rigors of experimentation, the poet investigates what is native, natural, and familiar to the human person, in order to nurture, cultivate, and console those qualities. This particularly refers to the passions, feelings, or emotions. The scientist proves the particular, the poet converses with the universal. The journalist reports the hour in its raw temporality, the poet retains it, but circumscribes it by wisdom and love. Wordsworth’s ballads were his way of giving us the drama of ordinary, or normative, “incident,” and his poems in blank verse served specially to lead us from the experience of incident toward the contemplation of the timeless and universal.

In this Wordsworth leads us back to Aristotle in his discussion of the distinction between poetry and history. It is not merely being cute to observe that the classical historian took as subject of his inquiries not the past but recent events and in this was more akin to the investigative journalist than to our modern conception of the historian. Herodotus really was a kind of newspaperman. Aristotle writes, in response,

the poet’s function is to describe, not the thing that has happened, but a kind of thing that might happen, i.e. what is possible as being probable or necessary. The distinction between historian and poet is not in the one writing prose and the other verse—you might put the work of Herodotus into verse, and it would still be a species of history; it consists really in this, that the one describes the thing that has been, and the other a kind of thing that might be. Hence poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars. By a universal statement I mean one as to what such or such a kind of man will probably or necessarily say or do . . . (Poetics 1451b)

The historian reports the singular in itself. The poet, without ever leaving the plane of the imitation of singulars, shapes the imitation so as to suggest the universal. The poem tells us not merely the incident that happened but—on Aristotle’s account—the moral significance, the good and evil, of the character, the action, and its consequences.

Sir Philip Sidney’s Defense of Poesy (1595), which is in part a commentary on Aristotle’s text, would celebrate the poet as the perfect synthesis of historian and philosopher. His wisdom is equal to that of the philosopher, but his medium eschews logical abstraction and remains the concrete dramatization of experience found in the historian. It is not news at all, for it does not pretend to tell the literal truth of fact. But poetry “stays” indeed, because what it conveys conforms to the universal laws by which we know at once how the world most likely works and where that operation stands in relation to the human good. Pound and Williams’ accounts of poetry echo Aristotle but in a perverse way that remains in thrall to just that love of incident and passion Wordsworth had decried as the brutalizing revolution of the modern age.

Reporter’s Notebook

Poets after Pound and Williams sought to recover some of the literary and philosophic luggage and also to keep up with the news without being overwhelmed by it. We see this in Louis MacNeice’s classic Autumn Journal (1939), which documents the events leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War, but does so in the reflective mode of the classical humanist who sees the particular always calling us to universal understanding, but who also appreciates that the particular is the place of our lives and is neither to be despised to merely left behind. MacNeice’s voice errs on the side of sloppiness and over-familiarity of style, but only just, as in passages such as this one:

All that I would like to be is human, having a share

In a civilized, articulate and well-adjusted

Community where the mind is given its due

But the body is not distrusted

Beginning his career just a decade later, the American poet Robert Lowell struggled to find a poetic medium at once attuned to the present crises of history and their universal significance. Much of his early work is situated by title in some particular moment of the Second World War, but the language of the poem itself follows the metaphysical poets in its ingenious complexity of symbolic wit. It is ornate and requires a great deal of abstract cogitation, even as its language is concrete and hard as a cut jewel.

In his later career, Lowell would effect a closer reunion between poetry and the news in his many “notebook sonnets”: long sequences of fourteen-line, blank-verse poems that are often finely wrought but much more direct and literal in their reportage than the early work. This includes his quoting, without permission, the letters of his ex-wife—a kind of documentarian approach to poetry first pioneered in Pound’s Cantos. Many of his later poems rewrite the subjects of the early, more ornate and indirect work, in familiar terms; his theme remains the same, the only thing that changes is his attempt to render poetry more closely and, in a double sense (confessional and reportorial), a kind of journalism.

Such a history of poetic practice was much on my mind, nearly a year ago, when I sat to down write the poems that became Quarantine Notebook, a long poems in blank verse, comprising fifteen parts, that documents the events from the beginning of the corona-virus shutdown, in mid-March 2020, until the restrictions began to lift two months later, in late May. The title of course nods to Lowell. Whereas Lowell produced sheaves of short poems, mine were long narrative and meditative lyrics, often meandering from literal subject to subject, with details accumulating around the base of an unstated theme.

That probably sounds, and probably should sound, a good deal like Pound’s accumulation of “luminous details” in his poetry. But the differences that emerge from there were, I think, stark. Pound’s “free verse” imitated the fragmentary, typographic hijinks of newsprint to convey meaning. My verse was the iambic pentameter of Shakespeare, Milton, and Thomson, of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and John Betjeman. Pound delighted in clipping sentences to fragments, and fragments to brief phrases, even single words. I aimed to practice the balanced sentence and complex syntax of the blank verse tradition, as it moves, as subject requires, from the simple and the prosaic to the complex period and the ornate, from the literal and concrete detail to the abstract reflections in which our ideas find fulfillment.

The notebook was a chronicle indeed, but I trusted the verse itself to confer on the ephemera of passing events the kind of permanence that comes only with well-weighed syllables and sound measure. There are moments in the poem indeed where I sought merely to render episodes from daily life or the news as verse and leave it at that. In the first poem, for instance, I mentioned the vulgar but familiar detail of “virtue signaling” on social media, and in the uncharitable terms of my own initial grouchiness, as the grocery stores were gutted by panicked shoppers:

Our shops are being ransacked, shelves stripped bare,

Even the fruits and vegetables are gone.

And all because of some sharp woman’s panic

(Her years of playing activist on Facebook,

With all those postured sentiments, give way

To hoarding claws and serious, darting eyes),

The cunning of some man who sees his love

Ends quite precisely where the fence line runs.

Elsewhere in the poem, I took particular delight in rendering in pentameters features of our public life that seem otherwise to be consigned to oblivion, if only by our own willful forgetting, such as the President’s daily virus task force briefings:

And he, up at the rostrum every day,

Reciting unrehearsed but scripted comments

In such a soporific drone, we think,

His mind is elsewhere, limbering for the spat

Set to ensue the moment he extends

A finger, puckers up that face, and tilts

His head, to take the first outrageous question.

What first inspired the poem was that moments like this one were not just private ones and that, in fact, American life had attained to a symbolic unity and commonality despite our fractured culture, political divisions, and antagonistic encounters in the mass and social media. By this I by no means intend we had somehow all grown closer together or that anyone believed the ads on the news or in the newspapers that “We’re all in this together.” As a moral statement, nothing could have been more obviously false. Suspicion and acrimony descended more quickly than the virus could spread.

My observation was not moral but metaphysical. Much of my poetry has taken for theme the exploration of reality as what Dante called “polysemous.” Things mean things, and the depths of their significance, with a little attention, opens up in a fashion more profound and universal than even Pound assumed with his theory of the luminous detail. As Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, “This world” that God has made “is word, expression, news of God.” The properly human way of facing the world is that of listening, of seeking to hear within the literal world of created things, what they say about themselves, what they say about their relations to one another, what they say about us, and what they have to tell us about the Creator. (See, for instance, “Autumn Road” at the conclusion of The Hanging God.)

Quarantine revealed something else within that reality. The public events being played out on the news all persons were encountering together; we were seeing the same thing, yes. In private, under quarantine, everyone was also enduring the same travails, from toilet paper shortage and home schooling to psychological distress and isolation. The lives of others were reflected in our private lives, and public events were all reflected in one anothers’ eyes, as they played out upon screen after screen after screen.

But that was not all. The public events seemed symbols and allegories of the private, and the private dramas gave expression to public crises. Think only of the mask. An abyss of significance, moral and social and political, medical and spiritual, opens up within it. Without ever ceasing to be a piece of cloth, it contains myriads, it is much more than that. All things were speaking to one another, informing one another, taking on meaning in light of one another—and all without the slightest cooperation from us or even the license of our good will. This I wanted to capture.

In March, the site where a new home was being constructed down the block fell silent. I watched its dark, exposed, idle emptiness for two months. Sitting out in the yard on the first warm and sunny day we had this spring—it finally came as May approached its end—I heard a noise. It was the sound of hammers resuming their work, the sound of a circular saw screaming through a sheet of plywood, the call of voices, each to each, up on a half-shingled rooftop. The quarantine had ended, the forced redundancy of those workers had ended, the cold of a cold spring had ended, and my poem, I knew, had ended with them. There were no more news items of that kind to report; they had taken their place in the permanence of verse, had been swept up into the eternal symbolism, the mythology, that Aristotle and Wordsworth tell us lead to wisdom and are its lasting fruit. The news had become poetry at last.

James Matthew Wilson is Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities and Augustinian Traditions at Villanova University. He is also Poet in Residence at The Benedict XVI Institute, Poetry Editor for Modern Age, and Director of the Colosseum Institute.

Nothing more aptly expresses the uncertain place of poetry in the modern age than American poet Ezra Pound’s pronouncement, in his ABC of Readings, that “Literature is news that STAYS news.” His old friend, William Carlos Williams, would faintly echo the thought, in “Asphodel, that Greeny Flower,” two decades later, when he wrote,

Both Pound and Williams want, clearly enough, to attach poetry to the news by some means, in the middle of that century during which, as Albert Camus wrote, modern man “fornicated and read newspapers.” Poetry has always occupied an uncertain place in our civilization, but the cause of that has varied from time to time. And, though the newspaper is a quintessentially modern thing—cheap, mass-produced, suitable only for an age where literacy is widespread, boredom yawning wide, and information both freely-dispensed and super-abundant—the news serves as a figure not only for the modern age but a whole host of other aspects of our civilization, some of them ancient.

It may seem one thing for a poet trying to sell his wares and another to puzzle over the purpose of human life. It may seem one thing to make claims upon a poem’s “newsworthiness” or, as Williams does, to insist that there is something in poetry that human beings need—mortal stakes—that cannot be found in the news, and another to ponder the nature of knowledge and of the human person as a knower; one thing to talk about literary value or permanence and another to speculate on aspirations of the soul to immortality, but, indeed, the questions are closely connected.

It is not news that human beings are entirely sunk down in the fluctuations of being, what Plato called the realm of becoming, such that everything on which our eyes fall is always swiftly passing away. Diotima tells Socrates as much in the Symposium, reminding him,

Even while each living thing is said to be alive and to be the same—as a person is said to be the same from childhood till he turns into an old man—even then he never consists of the same things, though he is called the same, but he is always being renewed and in other respects passing away, in his hair and flesh and bones and blood and his entire body. And it’s not just in his body, but in his soul, too, for none of his manners, customs, opinions, desires, pleasures, pains, or fears ever remain the same, but some are coming to be in him while others are passing away. (Symposium 207d-e)

The enduring question is whether anything survives or stands apart from this passage of evanescence. Diotima proceeds to show Socrates that everything that matters stands apart from the fleeting becoming of things.

The peculiarly modern question is whether what might survive it is of any value, or if the knowledge of swiftly passing things is all that we require, is fuel for the bonfire of reality, and so the very basis for anything’s demand on our attention. News is the speech that passes, such that nothing is so old as yesterday’s newspaper. And yet it seems as if our every glance over the newsprint running before us already and immediately calls out for something more lasting, something permanent.

When Pound and Williams appeal to the news in talking about poetry, they acknowledge that craving for permanence even as they put in doubt its reality. They want to justify being in terms of becoming, the stable in terms of the flux, because they, like us, know the flux already—they are sunk down deep within it—and are not entirely sure it will be possible to argue their way out of it the way Diotima did so confidently before Socrates, millennia ago.

Pound’s Fish Heads Wrapped in Newspaper

Pound and Williams were part of the first generation of poets to compose upon the typewriter. Their poems first appeared—not in publication, I mean, but for the very first time before their eyes, in the privacy of their rooms—already under the guise of newsprint, that is to say, as type. Their fellow poet, T.S. Eliot, wrote directly of the effect of the typewriter on his work of composition—it led to brevity and clarity, we may be surprised to hear, rather than to length and elaboration. The machine as machine took the private thought out of the realm of overflowing sentiment and gave it the austere clarity of thought. Type, for Eliot, was chastening and austere.

Pound’s commentary on the effect of writing in type can be gleaned from his extra use of spaces and periods between words, in poems and prose alike, as if the machine itself could impress a weighty pause. His prose is so wholly dependent on the expressivity of newsprint that much of what he communicates he does by isolating lines in the middle of a page, letting paragraphs appear as torn fragments from a page, and having emphases announce themselves by words in all capitals. Pound’s hammering both blank spaces and majuscules with typewriter keys echo the ancient practice of the epigram, the short poem that takes its name from having been carved in stone: type itself seems to make the poem at once more contemporary, like newspaper headlines, but also more lasting, because it is a mechanical production rather than a mere manuscript.

So also, in Williams’s case, the lines we quoted above, with their three-line steps, seem to have come about by a strictly technological necessity: Williams’ eyes were failing with old age, and typing the lines out that way made it easier for him to read (a verse form for “a blind old man”). The result is a text that, on the one hand, must have seemed stamped—made permanent, published—simply because it first appeared as type rather than script, but which also resembles the endless eruption and superannuation of strings of tickertape at the stock exchange. Decades later, the poet A.R. Ammons would outdo Williams in the use of exogenous technology as a substitute for technique intrinsic to the art by composing a long poem on tickertape. In all of this, the typewriter as personal newspaper press seems to have given the poets, at once, a heady feeling of flirting with the really evanescent, but up-to-date, of technology and also the seeming ever-lasting permanence of printed books in the library.

For Pound, the news involved much more than a literal fixation on the technology behind, to use our familiar synecdoche for newspaper journalism, “the press.” The news implied a whole way of thinking about knowledge. In The ABC of Reading, be begins by complaining of the “European” propensity to move from the perception of the concrete individual by way of abstraction to the universal idea. “If you ask him what red is, he says it is a ‘colour.’” Against this, he offers us a version of the famous story of the Swiss-American naturalist Louis Agassiz and the fish. As the story goes, an applicant to study with Agassiz comes for an interview. Agassiz brings out a fish preserved in a jar with “yellow alcohol” from his supply of samples, and asks the student what it is. “That’s only a sunfish,” the student replies, in Pound’s telling. That is not good enough. The student is left alone with the sample for days to study it, to perceive it in all its particularities, and, eventually to write “a four-page essay” on it.

Modern science, for Pound, does not seem to be the process of empirco-mathematical abstraction and mechanistic reduction that it is normally taken to be. That is, modern science does not continue the “European” proclivity for abstraction, simply redirecting its concern from unconditioned truths to physical laws subject to our manipulation, as Descartes and Hobbes had proposed. Science is about patient observation of the concrete particular.

In Pound’s telling, an important detail of the anecdote is changed: “At the end of three weeks the fish was in advanced state of decomposition, but the student knew something about it.” The fish is not preserved, but rather rots before the eyes of the disciple. Pound is so averse to abstraction that he wants the thing under observation to show us nothing lasts; abstract reasoning is a kind of pickling of ideas and Pound wants no part of it. Knowledge is attained not by way of making universal observations that transcend the individual at hand, but rather, in the transference of the particular thing decaying before us into the no less particular thing that is the “four-page essay,” the text in print. The second half of the ABC of Reading consists mostly of individual samples—poems from the tradition—that made an original contribution to the development of poetry. Pound reluctantly offers commentary so that we see the innovations, but he would rather allow the scraps to show themselves by themselves just like the sunfish on the laboratory table.

For Pound, knowledge is attained by way of biological science, but science itself has been reformulated so that it is more akin to the news in the papers. It is not universal laws we learn there, but particulars: a thousand rotting fish heads. In the span of his poetry, this occurs in roughly three ways. His early lyrics consist of fragmentary moments of dramatic monologues. They are like the poem of Robert Browning, but with everything but the emotional climax lopped away; or so he described them to Williams, in an early letter (1908):

To me the short so-called dramatic lyric . . . is the poetic part of a drama the rest of which (to me the prose part) is left to the reader’s imagination . . . I catch the character I happen to be interested in at the moment he interests me, usually a moment of song, self-analysis, or sudden understanding or revelation.

The result, to mix metaphors, is a somewhat constipated production as hard as a kidney stone. Such news stays news, because all the prosaic details have been allowed to pass away indeed and all that is left is the concentrated moment of emotion—which emotion is justified only by hint or suggestion of its cause.

Pound never lost his attachment to Browning and, to the end, his poetic sensibility remained almost entirely the product of the Victorians. But he felt badly about that, and tried to escape it. During the years of the First World War, he came under the influence of the English art-critic and occasional poet, T.E. Hulme. Hulme wrote a great deal while a young man, and then was killed in the War; his mind was still in an early stage of growth and it would be too much to expect his ideas all to make sense together. What Hulme is best known for is his account of modernist abstraction in the visual arts as a way of representing eternal mathematical and religious truths, the permanent, so that it shocks us and makes us conscious of our own pitiable evanescence as biological and emotional creatures. Every cubist hunk of stone was an up-to-date death’s-head for the machine age, stirring us to recall our mortality and to seek that which is above.

Hulme’s handful of poems look like roughly chiseled epigrams of stone, and so would seem to identify poetry with the eternal rather than the temporal. But, in fact, when he speculated about poetry, Hulme equated it to the leaflet or the newspaper. “I am of course in favor of the complete destruction of all verse more than twenty years old,” Hulme wrote, advocating the short, free-verse poem as something to be written quickly, distributed and read, and then left in the bin, so that a new generation’s work could come into being, totally unincumbered by the past. Pound would write many poems that indeed look like short news stories, or letters to the papers, their rhythms crude, their language colloquial and unmemorable, as in “Salutation the Third,”

Later, Pound would explore a different intermingling of poetry, science, and newspapers, in his Cantos. While there is much warmed-over Victorian lyricism in that poem, and such passages, in fact, account for almost all its memorable lines, the greater bulk of it consists of unreadable or barely readable passages meant to serve as what Pound called “luminous details.” Such details were particular items no less individuated than Agassiz’s fish, but in whom one could find “incarnated,” as it were, the gestalt of an entire historical age. Such details are not intended to function as symbols, which unite the universal and the particular as Christ joins human and divine natures, but rather like points on a map that hint at the map as a whole—or, rather, as a “periplum”

Periplum, not as land looks on a map

But as sea bord seen by men sailing. (Cantos LIX)

News stays news not by finding distilled or abstracted, timeless expression, but by the concrete detail conveying our subjective experience of “sailing” through the whole of history. This becomes clear in the ABC of Reading, where the chief “innovation” Pound celebrates is the movement of poetry away from “Popean comment,” by which he means abstract and witty sentences, toward “conveying information.” That by “literature” Pound refers to poetry more than to prose is also made clear early in that book, when Pound contrasts the “Homeric poems,” which one reads again and again, with detective stories, which one only gives a second reading if one read carelessly the first time and has forgotten the ending.

The Cantos makes for unpleasant reading, even as, like so much modernist literature, it continues to attract scholars just because there are so many points to “map,” that is to say, to annotate. In doing so, scholars get to participate in the scientific endeavor as Pound understood it; observing all that lies hidden within the inevitably inadequately “luminous” detail. Poetry itself annotates or maps the news, providing us an account of the whole of historical reality without ever leaving the plane of that reality. We see that the cumulative effect of Pound’s entire career in poetry was just an accumulation: particular images, particular snatches of speech or sound, particular historical innovations, meant to resist abstraction and to substitute for abstract knowledge’s natural role in giving us a sense of the whole.

Williams’s Pressed Flowers

Williams’s work, in its own day and ours, has often been described as “anti-poetry.” The Irish poet Denis Devlin once wrote of him that he “threw out all the literary luggage” and yet “continues to stand peering, in a mixture of rage and uncertainty, over the threshold of poetry.” Williams’s condemnation of poetic form, refined speech, and (somewhat inconsistently) allusion to the literary tradition were lost with the suitcases. The result was a poetry as committed to the particular detail as Pound’s but also committed to eschewing all poetic diction as un-American.

Sometimes his poems genuinely seem to aspire to give us the news, as in the early “At the Ball Game,” which celebrates mass culture while also remarking the threat of mass man to lash out in mob violence (of the crowd in the stands, he writes, “This is / the power of their faces”). “Asphodel” is a love poem to his wife; he first compares the poem itself to a book he kept with pressed flowers that “retained / something of their sweetness / a long time,” but as the poem continues, it admits into itself the “flower” of the nuclear bomb, the threat of nuclear war, which is always in the news and sickens everyone with its incessance. The result is poetry that gives us old news—conventional themes of love and lust—in the language of the newspapers, to be written and read quickly and not always thoughtfully. If news travels fast, Williams does not aim for something slower or more stable, but merely hastens to keep up. The “odor” of petals fades and the spectacle of the bomb confronts us in every headline.

The irony of Williams and Pound’s efforts to justify poetry in terms of the news is that, up until their time, poetry had played its part in helping us get the news. Oral street ballads, printed poetry broadsides, and newspaper verse were common enough ways of sharing information up until their day. Pound and Williams sought to remake American poetry specifically by rejecting such popular predecessors as the Fireside poets, especially Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. But Longfellow’s “Poems on Slavery” were propaganda that served roughly the purpose of a newspaper editorial and worked to significant effect in changing northern attitudes to the peculiar institution. Moreover, his “Paul Revere’s Ride” is still the way in which many American children first learn of the battle of Lexington and Concord. Longfellow’s poetry is always memorable but often stereotyped. In this it resembles a news story much more closely than any of Pound’s luminous details. Further, when we read it, we can name “what is found there” more easily than we can in reading Williams’s work: the poetic luggage is there, of meter and rhyme, incantatory phrasing that is easy to recite aloud and hear as musical, to retain and perform again.

It’s All Old News

Why Pound and Williams should have framed their understanding of poetry in terms of the news is not hard to discern. From what I have observed already, we see that it conjured up associations with the new technology of the typewriter; with concrete scraps of information rather than with abstract and universal generalization; with one—eccentric!—account of the modern sciences and scientific progress; and, through Hulme, with the ephemeral publications of the modern city—leaflets, advertisements—that are the equipment serving the habits of modern mass culture’s marketing campaigns, fast fashions, and continuous consumption. This left Pound in the odd position of advocating poetry as news that stays news even as his account of literary history was one that emphasized the need for constant innovation and experiment; permanence had a vexed, probably incoherent, position in his view of things, but he could not let go of it altogether.

We gain a better understanding of the uncertain, often contradictory, ideas of Pound and Williams if we simply look back to earlier moments in literary history where poetry and the news were in one way of another brought into tension. I will mention just three, with reference to John Dryden, William Wordsworth, and Aristotle.

In Dryden’s Socratic dialogue, “Essay on Dramatic Poesy” (1668), the persona Crites, in his defense of the ancient drama against that of the moderns, observes that the ancients, in a short span, developed the art to mature perfection. Our age has its own proper “genius,” but it excels not in the arts but rather in the sciences. The “virtuosi” of Christendom have conducted so many “useful experiments in philosophy” as to have “revealed to us” “almost a new nature.” Crites’s aim is to vindicate the supposed “Three Unities” of Aristotle and affirm the deference to them exhibited by the playwrights of the time. Dryden’s other personae prove game in showing that the Augustan style indeed displays a progress that, while imitative of the ancients, in many ways is also innovative.

But, as Timothy Steele observes in Missing Measures (1990), Dryden’s dialogue is one of the first modern texts to exhibit anxiety that poetry may be permanently stalled, even if stalled only because perfectly achieved, while the new sciences proceed apace to unbounded progress. Steele argues that the abandonment of rhyme and especially meter in the age of Pound and Williams came, in part, as a response to this mounting anxiety. If poetry was to participate in the modern age, it must exhibit at least some analogue of experiment, innovation, and progress. The alternative was not permanent achievement but stagnation.

Pound aligns poetry and science alike with the news as media to “convey information” regarding “luminous details,” that remain always in the concrete and in the continuous rush of the news cycle. The news never ascends from its bits of fact to a universal or abstract law. News that stays news is not the equivalent of permanence but of the continuous repetition of a singular experience somehow kept fresh. Such an understanding of poetry as news is suggested by Pound’s response to Matthew Arnold’s definition of poetry as a criticism of life: “‘Poetry is about as much a ‘criticism of life’ as red-hot iron is a criticism of fire.”

In allying the role of the poet with Agassiz, Pound rightly captures the way in which the object of poetry is at least as much our concrete experience of the truth as the universal truth itself. It has a responsibility to pay attention and to see clearly. But doing so is a matter of being thoughtful, and thoughtfulness ought to culminate—every so often—in the achievement of some actual thought. Pound tried to resist that conclusion, first, by misinterpreting science as somehow less dependent on abstraction than such other endeavors as philosophy and theology and, second, by equating its “information” with the perpetual novelty of the spread of particulars to be found in newspapers.

Writing a century before Pound, William Wordsworth, in his “Preface to the Lyrical Ballads,”thought the enduring role of poetry to be almost the antithesis of what Pound would argue. In a manner akin to Pound, he holds that poetry is “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” and so entails a direct immersion in the stream of experience that, for Pound, is summed up by the “news.” But poetry is also “emotion recollected in tranquility”; it is the product of mature philosophical reflection so that the immediacy of sensuous experience is deepened, completed, and stabilized in the steady gaze of wisdom.

Wordsworth was writing in the wake of the French Revolution, the first major political event to befall the modern age as a consequence of the rise of urban life and its saturation in cheaply-printed opinion and discussion. Wordsworth laments that modern persons, especially in the cities, are subjected to “gross and violent stimulants”:

For a multitude of causes, unknown to former times, are now acting with a combined force to blunt the discriminating powers of the mind, and unfitting it for all voluntary exertion to reduce it to a state of almost savage torpor. The most effective of these causes are the great national events which are daily taking place, and the encreasing accumulation of men in cities, where the uniformity of their occupations produces a craving for extraordinary incident, which the rapid communication of intelligence hourly gratifies.

Information assails the mind, brutalizes it, and makes it the instrument of revolutionary passions. The poet serves to recall us to ourselves, to call us away from the cry of news in the street, to a more natural place (indeed, to Nature herself), a place in keeping with our human natures, wherein we can recollect our true selves.

The poet’s attentions are philosophical rather than scientific. Rather than seeking to discover truths that one would not even have suspected, were it not for the rigors of experimentation, the poet investigates what is native, natural, and familiar to the human person, in order to nurture, cultivate, and console those qualities. This particularly refers to the passions, feelings, or emotions. The scientist proves the particular, the poet converses with the universal. The journalist reports the hour in its raw temporality, the poet retains it, but circumscribes it by wisdom and love. Wordsworth’s ballads were his way of giving us the drama of ordinary, or normative, “incident,” and his poems in blank verse served specially to lead us from the experience of incident toward the contemplation of the timeless and universal.

In this Wordsworth leads us back to Aristotle in his discussion of the distinction between poetry and history. It is not merely being cute to observe that the classical historian took as subject of his inquiries not the past but recent events and in this was more akin to the investigative journalist than to our modern conception of the historian. Herodotus really was a kind of newspaperman. Aristotle writes, in response,

the poet’s function is to describe, not the thing that has happened, but a kind of thing that might happen, i.e. what is possible as being probable or necessary. The distinction between historian and poet is not in the one writing prose and the other verse—you might put the work of Herodotus into verse, and it would still be a species of history; it consists really in this, that the one describes the thing that has been, and the other a kind of thing that might be. Hence poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars. By a universal statement I mean one as to what such or such a kind of man will probably or necessarily say or do . . . (Poetics 1451b)

The historian reports the singular in itself. The poet, without ever leaving the plane of the imitation of singulars, shapes the imitation so as to suggest the universal. The poem tells us not merely the incident that happened but—on Aristotle’s account—the moral significance, the good and evil, of the character, the action, and its consequences.

Sir Philip Sidney’s Defense of Poesy (1595), which is in part a commentary on Aristotle’s text, would celebrate the poet as the perfect synthesis of historian and philosopher. His wisdom is equal to that of the philosopher, but his medium eschews logical abstraction and remains the concrete dramatization of experience found in the historian. It is not news at all, for it does not pretend to tell the literal truth of fact. But poetry “stays” indeed, because what it conveys conforms to the universal laws by which we know at once how the world most likely works and where that operation stands in relation to the human good. Pound and Williams’ accounts of poetry echo Aristotle but in a perverse way that remains in thrall to just that love of incident and passion Wordsworth had decried as the brutalizing revolution of the modern age.

Reporter’s Notebook

Poets after Pound and Williams sought to recover some of the literary and philosophic luggage and also to keep up with the news without being overwhelmed by it. We see this in Louis MacNeice’s classic Autumn Journal (1939), which documents the events leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War, but does so in the reflective mode of the classical humanist who sees the particular always calling us to universal understanding, but who also appreciates that the particular is the place of our lives and is neither to be despised to merely left behind. MacNeice’s voice errs on the side of sloppiness and over-familiarity of style, but only just, as in passages such as this one:

All that I would like to be is human, having a share

In a civilized, articulate and well-adjusted

Community where the mind is given its due

But the body is not distrusted

Beginning his career just a decade later, the American poet Robert Lowell struggled to find a poetic medium at once attuned to the present crises of history and their universal significance. Much of his early work is situated by title in some particular moment of the Second World War, but the language of the poem itself follows the metaphysical poets in its ingenious complexity of symbolic wit. It is ornate and requires a great deal of abstract cogitation, even as its language is concrete and hard as a cut jewel.

In his later career, Lowell would effect a closer reunion between poetry and the news in his many “notebook sonnets”: long sequences of fourteen-line, blank-verse poems that are often finely wrought but much more direct and literal in their reportage than the early work. This includes his quoting, without permission, the letters of his ex-wife—a kind of documentarian approach to poetry first pioneered in Pound’s Cantos. Many of his later poems rewrite the subjects of the early, more ornate and indirect work, in familiar terms; his theme remains the same, the only thing that changes is his attempt to render poetry more closely and, in a double sense (confessional and reportorial), a kind of journalism.

Such a history of poetic practice was much on my mind, nearly a year ago, when I sat to down write the poems that became Quarantine Notebook, a long poems in blank verse, comprising fifteen parts, that documents the events from the beginning of the corona-virus shutdown, in mid-March 2020, until the restrictions began to lift two months later, in late May. The title of course nods to Lowell. Whereas Lowell produced sheaves of short poems, mine were long narrative and meditative lyrics, often meandering from literal subject to subject, with details accumulating around the base of an unstated theme.

That probably sounds, and probably should sound, a good deal like Pound’s accumulation of “luminous details” in his poetry. But the differences that emerge from there were, I think, stark. Pound’s “free verse” imitated the fragmentary, typographic hijinks of newsprint to convey meaning. My verse was the iambic pentameter of Shakespeare, Milton, and Thomson, of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and John Betjeman. Pound delighted in clipping sentences to fragments, and fragments to brief phrases, even single words. I aimed to practice the balanced sentence and complex syntax of the blank verse tradition, as it moves, as subject requires, from the simple and the prosaic to the complex period and the ornate, from the literal and concrete detail to the abstract reflections in which our ideas find fulfillment.

The notebook was a chronicle indeed, but I trusted the verse itself to confer on the ephemera of passing events the kind of permanence that comes only with well-weighed syllables and sound measure. There are moments in the poem indeed where I sought merely to render episodes from daily life or the news as verse and leave it at that. In the first poem, for instance, I mentioned the vulgar but familiar detail of “virtue signaling” on social media, and in the uncharitable terms of my own initial grouchiness, as the grocery stores were gutted by panicked shoppers:

Our shops are being ransacked, shelves stripped bare,

Even the fruits and vegetables are gone.

And all because of some sharp woman’s panic

(Her years of playing activist on Facebook,

With all those postured sentiments, give way

To hoarding claws and serious, darting eyes),

The cunning of some man who sees his love

Ends quite precisely where the fence line runs.

Elsewhere in the poem, I took particular delight in rendering in pentameters features of our public life that seem otherwise to be consigned to oblivion, if only by our own willful forgetting, such as the President’s daily virus task force briefings:

And he, up at the rostrum every day,

Reciting unrehearsed but scripted comments

In such a soporific drone, we think,

His mind is elsewhere, limbering for the spat

Set to ensue the moment he extends

A finger, puckers up that face, and tilts

His head, to take the first outrageous question.

What first inspired the poem was that moments like this one were not just private ones and that, in fact, American life had attained to a symbolic unity and commonality despite our fractured culture, political divisions, and antagonistic encounters in the mass and social media. By this I by no means intend we had somehow all grown closer together or that anyone believed the ads on the news or in the newspapers that “We’re all in this together.” As a moral statement, nothing could have been more obviously false. Suspicion and acrimony descended more quickly than the virus could spread.

My observation was not moral but metaphysical. Much of my poetry has taken for theme the exploration of reality as what Dante called “polysemous.” Things mean things, and the depths of their significance, with a little attention, opens up in a fashion more profound and universal than even Pound assumed with his theory of the luminous detail. As Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, “This world” that God has made “is word, expression, news of God.” The properly human way of facing the world is that of listening, of seeking to hear within the literal world of created things, what they say about themselves, what they say about their relations to one another, what they say about us, and what they have to tell us about the Creator. (See, for instance, “Autumn Road” at the conclusion of The Hanging God.)

Quarantine revealed something else within that reality. The public events being played out on the news all persons were encountering together; we were seeing the same thing, yes. In private, under quarantine, everyone was also enduring the same travails, from toilet paper shortage and home schooling to psychological distress and isolation. The lives of others were reflected in our private lives, and public events were all reflected in one anothers’ eyes, as they played out upon screen after screen after screen.

But that was not all. The public events seemed symbols and allegories of the private, and the private dramas gave expression to public crises. Think only of the mask. An abyss of significance, moral and social and political, medical and spiritual, opens up within it. Without ever ceasing to be a piece of cloth, it contains myriads, it is much more than that. All things were speaking to one another, informing one another, taking on meaning in light of one another—and all without the slightest cooperation from us or even the license of our good will. This I wanted to capture.

In March, the site where a new home was being constructed down the block fell silent. I watched its dark, exposed, idle emptiness for two months. Sitting out in the yard on the first warm and sunny day we had this spring—it finally came as May approached its end—I heard a noise. It was the sound of hammers resuming their work, the sound of a circular saw screaming through a sheet of plywood, the call of voices, each to each, up on a half-shingled rooftop. The quarantine had ended, the forced redundancy of those workers had ended, the cold of a cold spring had ended, and my poem, I knew, had ended with them. There were no more news items of that kind to report; they had taken their place in the permanence of verse, had been swept up into the eternal symbolism, the mythology, that Aristotle and Wordsworth tell us lead to wisdom and are its lasting fruit. The news had become poetry at last.

James Matthew Wilson is Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities and Augustinian Traditions at Villanova University. He is also Poet in Residence at The Benedict XVI Institute, Poetry Editor for Modern Age, and Director of the Colosseum Institute.

-->