My contribution to this conversation will be a modest one, the perspective of a parish pastor who has preached and taught through all of the New Testament texts to ordinary church folks for 35 years. When parishioners ask questions about the dating of New Testament books they are usually asking because 1) they want to have some confidence in their authenticity, and therefore, their reliability and/or 2) they recognize that the Gospels, Acts, and the apostolic letters are very often addressing matters that at first glance seem to be foreign to modern Christian living.

So on the one hand, apologetic challenges often give rise to questions about evidence for the accuracy and trustworthiness of what has been recorded. How confident can we be that the Gospels reliably document the acts and words of Jesus? Did Paul really pen these letters attributed to him? If, for example, the Gospels were penned decades after the ministry of Jesus, after many decades of oral transmission, can we trust the truthfulness of what we read?

And on the other hand, so much of the New Testament is addressing concerns that at first seem alien to us in the modern world. Why all the talk about Jews and Gentiles, circumcision, food laws, sabbath regulations, sacrifices, priests, the land, and the temple? How does it all fit together? And what are we to learn from disputes that don’t seem to connect with challenges that we face today?

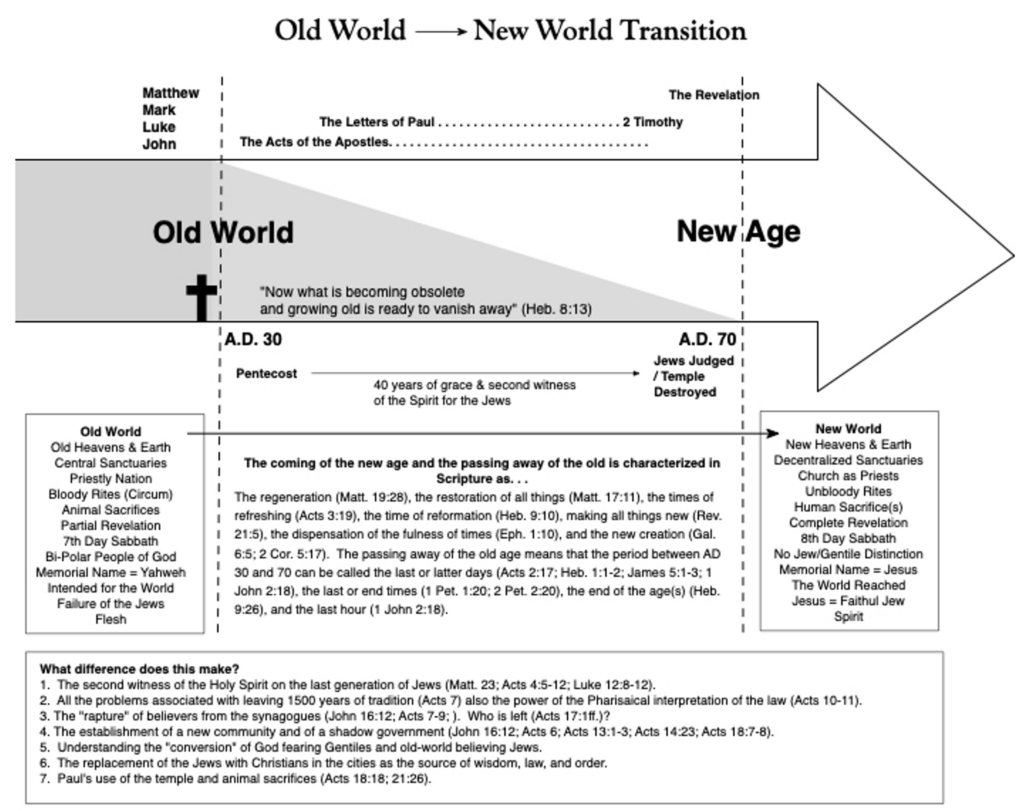

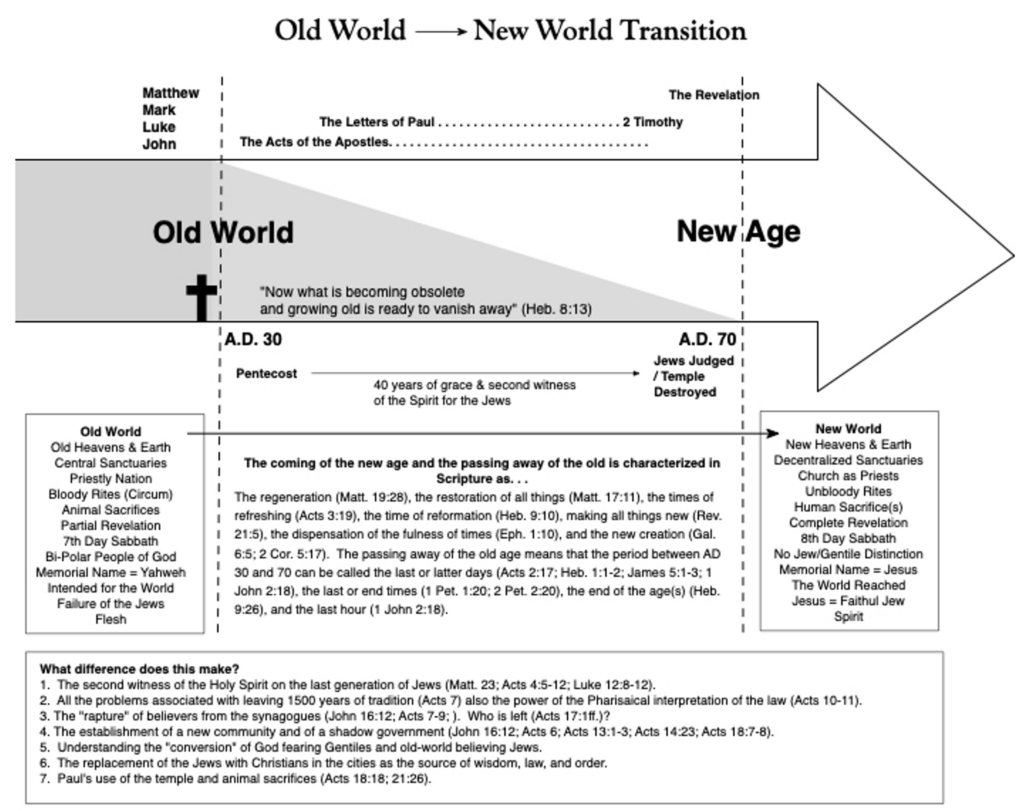

These two concerns are related. God reveals himself and his will for us by means of the situation of first century transition from the old world to the new. Jesus’ death, resurrection, ascension, and the out-pouring of the Holy Spirit inaugurated enormous changes, a ritual and social revolution, if you will. Dating these documents before the destruction of the Temple and the judgment against Jerusalem in A.D. 70 helps Christians understand the transitional situation addressed by the Apostles and enables us to make appropriate adjustments to understand how the narratives and letters apply to modern life.

Ralph Smith’s careful review and critique of Bernier’s Redating the New Testament helpfully addresses both common concerns. When I read Bernier’s book earlier this year, I spotted many of the concerns Smith has outlined. But he has courageously identified significant deficiencies in the way the academy has dealt with dating these documents and then proposes beneficial correctives. Before I offer my own contribution, let me highlight some of Smith’s more interesting points.

- There is no well-established consensus on dating these documents, especially the Gospels. Early dates have not been ruled out by present scholarship. Even the more liberal scholar John A.T. Robertson in his Redating the New Testament (1976) challenged the later dates so often assumed in post-Enlightenment academic research.

- Modern scholarship approaches questions about dating with theological and philosophical presuppositions that bracket traditional ecclesiastical convictions about the nature of these texts as divine revelation. This makes them susceptible to theories that place the New Testament documents later than the first century, often at the end of a long period of oral transmission, and composed as pseudepigrapha.

- Many scholars, including Bernier, fail to reckon with the decidedly Jewish persecution of the early church, especially before the latter half of the reign of Nero. The enemy of the nascent church in the New Testament is not Rome, but Jerusalem’s religious leaders. Roman officials are more often presented in a positive light in the Gospels and Acts, even acting as legal guardians to what they considered a Jewish sect. That changes in the later 60’s when Jewish and Roman persecutors align in their persecution of the church.

- If #3 is true, and can readily be established by a careful reading of the New Testament texts, then Bernier’s methodological approach of synchronization and contextualization situates the dating of these texts earlier in the first century that is commonly thought.

- A written account of Jesus’s teaching and ministry would have been needed very shortly after Pentecost. The proclamation of Jesus as the promised Messiah that began with the preaching of Peter and the other Apostles demanded a written account of the fulfilment of the prophecies contained in the Jewish Scripture. After all, the Jews were “people of the book,” as Smith notes.

- Smith’s summary of the disciple Matthew’s (Levi’s) qualifications for writing such an account are compelling. As a tax collector, Matthew would have been something of a bean counter and the ideal disciple to pen the first comprehensive account of how Jesus fulfilled all the narratives and predictions of the prophetic Scriptures. The early church needed a narrative that grounded all of Jesus’ ministry in the “it stands written” revelation of Israel’s prophetic tradition.

- Mark’s Gospel, grounded in Peter’s apostolic perspective, builds on Matthew. And I would argue Mark writes his account in the early 40s to comfort and instruct the increasingly persecuted church by emphasizing Jesus as the greater son of David, a royal figure who has been anointed king, but must keep his identify secret until he accomplishes his self-sacrificial death on the cross. The centurion is the first to identify him as the “Son of God” (a royal, Davidic title) when he observes how Jesus “breathed his last” (Mark. 15:39).

- The dating of Luke’s Gospel is less controversial (50s) for obvious reasons. Luke has clearly been influenced by Paul’s ministry, writing to the Gentile convert Theophilus (which may be a cipher for the whole Gentile Christian portion of the emerging church). And his second volume is completed before Paul’s trial in Rome (before A.D. 62).

- Smith’s criticism of Bernier and others who fail to address the importance of Jesus’ Olivet Discourse for establishing an early date for all of the New Testament books deserves careful attention. Not only does Jesus predict the judgment on Jerusalem and the “end of the age,” in the Synoptic Gospels, but Acts and all the New Testament letters are written with the expectation of an imminent judgment. The judgment on Jerusalem and the Temple signals the passing away of the old age, which is why the period between AD 30 and 70 can be called the last or latter days (Acts 2:17; Heb. 1:1-2; James 5:1-3; 1 John 2:18), the last or end times (1 Pet. 1:20; 2 Pet. 2:20), the end of the age(s) (Heb. 9:26), and the last hour (1 John 2:18).

Moving from the Old to the New

Perhaps this last point (#9) can be expanded a bit. At the end of his contribution in the conversation Mark Garcia writes,

A further, related nagging question in reading Smith’s piece is the fact that, outside his proposed reading of the Discourse, the New Testament rather consistently points to the passion and resurrection/ascension of Christ as his ushering in of the new world, and not the events of AD 70. Though I appreciate this pulls us into a range of arguments I can’t explore here, I would like to hear more of why Smith connects that new world to AD 70 as he does (p. 12) in comparison with the Apostolic focus on the passion and resurrection/ascension.

I’d like to try to help answer this question. There is no need to place the death and resurrection/ascension of Christ in competition with the reality of a new world connected with the judgment of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 AD. They are not at odds. In the Apostolic writings, they are connected. Jesus inaugurated a new world when he ascended into heaven and poured out his Spirit on the embryonic church. He got things started, but there was still much left to do—the second offer of repentance to the Jews, for example. John the baptizer warned the crowds who came to the Jordan river of an imminent, fiery judgment unless they repented (Luke 3:1-17).

“Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. . .” (Luke 3:9).

The one mightier that John is coming and “his winnowing fork is in his hand to clear his threshing floor and to gather his wheat into his barn, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (Luke 3:16, 17).

Jesus then begins his ministry by proclaiming repentance “for the kingdom of heaven/God is at hand.” Too often preachers and commentators miss how many times Jesus warns of a coming judgment. It would take too much space to reference all these prophetic warnings recorded by the Gospel writers. N.T. Wright’s gives extensive coverage in chapter 8 of his Jesus and the Victory of God (pp. 320-368). His observation is only too true:

The next comment ought to be unnecessary, but misunderstanding has been so long-lasting here that perhaps it is as well to be clear. The warnings already mentioned, and those about to be discussed, are manifestly and obviously, within their historical context, warnings about a coming national disaster, involving the destruction by Rome of the nation, the city, and the Temple. The story of judgment and vindication which Jesus told is very much like the story told by the prophet Jeremiah, invoking the categories of cosmic disaster in order to invest the coming socio-political disaster with its full theological significance (p. 323, emphasis mine).

On Pentecost Peter cites Joel 2, which prophesied both the Spirit’s outpouring and the coming “day of the Lord” (Acts 2:17-21). Joel describes that day with language that reminds us of Jesus’ many warnings of Judgment, especially the Olivet Discourse. At Pentecost the Apostles, empowered by the Holy Spirit, again warn the Jews—who are now guilty of crucifying their Messiah—of the coming Day of the Lord that can only be avoided by repentance and confession of Jesus as resurrected and ascended Lord (Acts 2:22-41).

The Holy Spirit speaking through the Apostles is the gracious “second witness” given by Jesus to the Jewish people. Unbelieving “words spoken against the Son of Man” during Jesus’ earthly ministry could be forgiven but. . .

. . . the one who blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven. And when they bring you [the Apostles] before the synagogues and the rulers and the authorities, do not be anxious about how you should defend yourself or what you should say, for the Holy Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say.” (Luke 12:8-12)

This gracious second witness of the Spirit to the Jews begins ca. A.D. 30 at Pentecost. Just as Jesus promised, the Apostles are given what to speak before the Jewish leaders and people. The book of Acts chronicles this in some detail. Even Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles, always goes “to the Jews first,” visiting the synagogues in the diaspora to reason with them from the Scriptures that Jesus was the Messiah. I hardly need to cite passages since this is so well known. But what is often missed is the significance of this forty-year time of testing (from AD 30 to 70) for our understanding of the dating of Gospels and the Apostolic epistles.

Would the Jews follow Joshua Messiah into the new age, the new world he inaugurated by his death, resurrection, ascension, and session as King at the right hand of his Father? Many did, but not all. At the end of Acts, Paul is in Rome still proclaiming to the Jews “the kingdom of God and trying to convince them about Jesus” (Acts 26:23). But they are recalcitrant. So quoting the prophecy of Isaiah 6:9-10 (the same passage Jesus used to explain why he spoke in parables), Paul alters his strategy. He has done his duty. The Jews have heard and refused to believe. They have sealed their fate. The forty years of grace are over.

When Jesus met with the Apostles on the day of his ascension, they thought that the resurrected Jesus would immediately “restore the kingdom to Israel” (Acts 1:6). This misunderstanding was not instantly corrected by Jesus. Why? Because their understanding of the nature and extent of Jesus kingdom needed to be formed by their experience of the unrepentance and vicious persecution of the Jewish authorities recorded for us in the book of Acts. Near the end of this history the Jerusalem Jews are so hardened against the Jesus and his church that they conspire to assassinate Paul, the chief priests and elders conspiring together in the plot (Acts 23:12-15). They are fulfilling Jesus’ prophecy in Matthew 23. Everything he predicted is happening during the apostolic age, and the judgment, therefore, is coming upon that generation.

“Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you build the tombs of the prophets and decorate the monuments of the righteous, saying, ‘If we had lived in the days of our fathers, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.’ Thus you witness against yourselves that you are sons of those who murdered the prophets. Fill up, then, the measure of your fathers. You serpents, you brood of vipers, how are you to escape being sentenced to hell? Therefore I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your synagogues and persecute from town to town, so that on you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of innocent Abel to the blood of Zechariah the son of Barachiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. Truly, I say to you, all these things will come upon this generation.” (Matt. 23:29-36)

What does this have to do with dating the books of the New Testament? And how does dating the books of the New Testament before the judgment against Jerusalem affect our understanding of their message? The Gospels and the all the epistles cannot be fully understood apart from the recognition that Jesus’ parable of the tenants of his vineyard is being fulfilled. Speaking to the chief priests, elders, and Pharisees, Jesus prophesies at the conclusion of that parable:

“Therefore I tell you, the kingdom of God will be taken from you and given to a people producing its fruits. And the one who falls on this stone will be broken to pieces; and when it falls on anyone, it will crush him” (Matt. 21:43, 44).

The New Testament everywhere testifies of this momentous change, the transition from a Jewish-centered, Temple-oriented socio-religious world to the new kingdom of the risen Lord Jesus. Even though the Temple is still standing during the Apostolic age, it has been side-lined by the new Spirit-indwelled temple of living stones (Acts 2; 1 Cor. 3), and will be destroyed, not one stone left upon another (Matt. 24:2). The old administration symbolized by the Decalogue was “written and engraved in stones,” and as glorious as it was, was nevertheless a “ministry of death” and was being supplanted by a more glorious reality.

“. . . what once had glory has come to have no glory at all, because of the glory that surpasses it. For if what was being brought to an end came with glory, much more will what is permanent have glory” (2 Cor. 3: 10, 11).

What Jesus had accomplished in his glorified, resurrected flesh was nothing short of a new creation.

“Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come” (2 Cor. 5:17).

“For neither circumcision counts for anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creation” (Gal. 6:15)

Those two references are not about an individual’s new heart (other passages attest to something like that). Rather, they testify to the newly fashioned, historical reality that Jesus has brought to pass; a reality oriented around his glorified Person that was inexorably changing the entire old way of life.

That old creation and its old way of life was characterized by the Apostle Paul as ta stoicheia tou kosmou, variously translated as “the elements of the world” or “the elementary principles of the world.”

I mean that the heir, as long as he is a child, is no different from a slave, though he is the owner of everything, but he is under guardians and managers until the date set by his father. In the same way we also, when we were children, were enslaved to the elementary principles of the world. But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God. Formerly, when you did not know God, you were enslaved to those that by nature are not gods. But now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God, how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world, whose slaves you want to be once more? You observe days and months and seasons and years! I am afraid I may have labored over you in vain (Gal. 4:1-9).

A careful reading of that passage will reveal that both the Jews (Paul’s use of “we”) and the Gentiles (addressing the Galatians with “you”) were both, before Christ, subject to immature bondage under “the elements.” Before Jesus ushed in the new age, everyone lived under the stoicheia. Although somewhat different for Jews and Greeks, the stoicheic life was a cultural and social world characterized by angelic management (Gal. 4:3; Col. 2:18; 1 Cor. 10:20; Heb. 1:1-14), purity laws (Acts 10; I Tim. 4:3; Col. 2:20-23), geographically defined zones of holiness (I Cor. 3:17; Heb. 9-10), stone temples (I Cor. 3:17; Eph. 2:21; 1 Pet. 2:5), bloody animal sacrifices (Heb. 9-10), a binary division of mankind into Jews and Gentiles (Eph. 2:11-22), sabbath regulations (Col. 2:16), a genealogical priesthood (1 Pet. 2:9; Heb. 7-8; Rev. 5:10), and more. (For a detailed analysis see Peter Leithart’s Delivered from the Elements [Intervarsity Press, 2016].) All of this was passing away. Jesus was not merely introducing a new “religion” of individual salvation, he overhauled the entire system. That stoicheic system was unravelling during the apostolic age. The judgment on Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in AD 70 would be the symbolic end of the old age.

It would be difficult to overestimate the hermeneutical significance of the transitional situation the apostolic writers addressed. It would be like some scholar five hundred years from now trying to make sense of the texts, letters, and the content of other forms of communication in 2020 without knowing about the COVID19 virus, thinking that he was reading texts written in 2045. Maybe that’s an unhelpful analogy because it’s so obvious to us. Nevertheless, what was obvious to the Apostles was what needed to be understood by Jews and Gentiles alike—that Jesus’ death, resurrection, and ascension had ushered in a new age. The old age with its central sanctuary, holy land, holy city, priesthood, food taboos, sabbath festivals, sacrificial system, circumcision, genealogies, and more—that entire way of structuring the ritual and social lives of Jews and Gentiles had served its purpose and was now passing away.

I have used this chart with students to help them visualize the transitional nature of the Apostolic age and appreciate the content of the Gospels and Epistles. Like every chart, it has its limitations.

How Early is Too Early?

I would like briefly to address another concern. In research for my James commentary, especially the dating of that letter, I found Bible scholars making unjustifiable judgments about “how early” the letter might have been written. Almost every commentator, even conservative Evangelical scholars, only have one big argument against the authorship of the Apostle James before his death at the hands of Herod Agrippa I in AD 44 (Acts 12:1-2)—it would be “too early.” Apparently for most scholars, a letter like this could not have been written so early in the apostolic age. Commentators repeatedly assure us of the “improbability” of dating this epistle during the life of James the Apostle. Peter Davids’s dismissal is representative: “James the son of Zebedee probably died too early to leave any literary remains.” He adds, “Acts 12 indicates that he died before AD 44, ruling out the probability, although not the possibility, of his writing the epistle” (The Epistle of James [Eerdmans, 1982], p. 6). Why is an early date so improbable? Nobody gives definitive reasons for this assessment. It’s just too early, they say. Motyer, however, gives us an honest appraisal:

It is usually thought that James son of Zebedee was martyred at too early a date (AD 44) for him to have been the author of the letter [of James]. Even this, however, cannot be maintained for certain. Nothing in the letter absolutely forbids a date as early as James the son of Zebedee, and certainly the arguments proposed for later dates lack impressiveness (The Message of James [InterVarsity Press, 1985], p. 18).

I suspect that behind the trepidation to date this epistle, as well as any of the Gospel narratives, within the first decade of the life of the church, is the assumption that the teachings of Jesus and the supervision of the fledgling Christian community was at first accomplished by means of oral communication alone. Before anything was written down, the stories and the instruction had to be passed on by means of oral tradition. That may have been true in Hellenistic cultures. But when it comes to the early Christian community we are dealing with Jews, a literary, bookish people. It is very difficult to believe that men who were convinced the promised Messiah had come—the one foretold in all their sacred writings and explicitly prophesied in the prophetic books of the Hebrew Scriptures—would wait decades before recording in writing such momentous events.

The fact that James is a circular letter makes the charge of it being “too early” even more questionable. After all, the epistles of the New Testament are all written by Paul, Peter, or John straightaway to deal with immediate problems and challenges in the churches. There was no intermediate oral communication. Even if there was personal, oral communication by means of representatives sent by these Apostles to the various churches, they more often than not carried with them letters to be read in the assembly (e.g., 1 Thess. 5:27). These are the letters we have designated the “New Testament Epistles,” and not one of them was written a decade or more after the events that precipitated the need for these written messages.

Given that James identifies the recipients of this letter (1:1, “to the twelve tribes in the dispersion”), we should consider the urgency of the communication to these Christians banished from Jerusalem by the persecuting leaders of the church. If the crisis referred to here is indeed the forced exile of Jewish Christians from Jerusalem, as recorded for us in Acts 8:1 and Acts 11:19, then it seems quite reasonable to believe that the Apostle James wrote this letter soon after their banishment to challenge these Jewish Christian believers. It would make sense to distribute a circular letter like this while these disciples are still separated from Jerusalem. But a dozen years or so after the initial banishment, after the death of the Apostle James (Acts 12:2), when James the brother of Jesus seems to have taken the leadership of the Jerusalem Christian community, the situation had changed. There appears to be a flourishing community again in Jerusalem (Acts 12:17; 15:1-21). If that exile from Jerusalem took place in the aftermath of Stephen’s martyrdom, a year or so after Pentecost, and only the Apostles remained in the city, then dating the letter sometime in the early to mid 30s makes more sense.

There are other compelling reasons to believe that James’s letter was composed very early in the life of the church. I have detailed those reasons in my commentary. I have used James as an example of the way many in academia too readily dismiss earlier dates for the composition of New Testament documents.

One other observation. Surely if Jesus commissioned the Twelve to be his “witnesses” and empowered them with the Holy Spirit who would guide them into all truth (John 14:25-26; 16:12-14), we would expect them to begin the work of testifying to Jesus immediately, and not just by preaching, but also by making and distributing written documents establishing Jesus as the promised Messiah. Composing the founding documents of the Messianic age would have been a large part of their vocation as Apostles. This is why Luke calls them “servants of the word”:

Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught (Luke 1:1-4).

I believe they took this mandate so seriously that they had to delegate authority to other men to distribute food to widows during the controversy narrated in Acts 6. As important as providing for the welfare of the widows in both the Hebrew and Hellenstic communities might have been, their calling as servants of the Word took precedence.

And the twelve summoned the full number of the disciples and said, “It is not right that we should give up the word of God to serve tables. Therefore, brothers, pick out from among you seven men of good repute, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we will appoint to this duty. But we will devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word.”

This story is often read by Presbyterians as a justification for pastors to concentrate on the preaching of the Word and an authorization to delegate other responsibilities to “deacons.” But the word “preaching” (ESV) is not in the original. The Apostles simply say, “It is not right for us to give up the Word of God to serve tables” (v. 2). Of course, it is appropriate to use this passage to illustrate the advisability of delegating authority in church communities. But the Apostles here in Acts 6 are not simply “ministers”—preachers that need to have their schedules free from distractions so they can prepare for sermons and pray. What if the Apostles, not wanting to “give up the Word of God,” meant that they were so engaged with collaborating to produce the written document (Matthew) that would provide a foundation for the fledgling Christian community that they could not let even widow care interfere with such a momentous project? I think the connection with Luke 1:1-4 makes that interpretation likely.

Back to my research on James’s epistle. By identifying himself in verse 1 as a “servant” (doulos) of God and the Lord Jesus Christ,” James would appear to be signaling his association with the other apostolic “servants of the word” (Luke 1:2). Unless there are some very good reasons to think otherwise, it seems reasonable to begin with the assumption that the author is indeed James the Apostle.

There are other compelling reasons to believe that epistle of James was composed very early in the life of the church. Many commentators have noted that 1) there is a decidedly Jewish flavor to the vocabulary and content, 2) James does not touch on common debates and controversies which occupied the apostolic church in later decades, 3) there is a “primitiveness to James’s theological framework . . . which is exactly what we would expect of a very early Christian writing” (Dan. G. McCartney, James [Baker Academic, 2009], p. 15), and 4) the letter is full of clear allusions to Matthew’s Gospel, and the correspondences to the Sermon on the Mount are well documented. This last feature of James fits with the post-apostolic church’s understanding of the relative order of the Synoptic Gospel accounts—that the canonical order is the order in which the Gospel narratives were written. Matthew’s gospel was either already composed and beginning to circulate or was in the process of being written, and James, as a member of the apostolic brotherhood, had some access to Matthew’s material. McCartney comes to a similar conclusion:

It is as though James is imbued with the wisdom teaching of Jesus, but not in the written form in which we now find it. All this points to a time quite early in the life of the church, prior to the theological reflections of Paul, prior to the circulation of the Gospels, and prior to the authors of Hebrews, 1 Peter, and the Johannine materials, or at least prior to the time when these other writings began to have widespread and determinative influence . . . James represents a state of Christian thinking that has not yet been determined by them, and hence is logically prior. (p. 8)

I would add that James is not merely grounding his admonitions on the “wisdom teaching” of Jesus, but he is also giving the persecuted community hope based on Jesus’ repeated prophetic denunciations of the failed leadership of the Jewish authorities (1:9-11; 2:6-7; 5:1-6; cf. Matt. 23) and the coming destruction of the Temple (Matt. 24). The exiled Church’s theocratically rich oppressors will be judged shortly, “for the coming of the Lord is near” (5:8). We are back to the hermeneutical significance of dating the New Testament documents before AD. 70. James 5 is not describing a generic judgment on rich “plantation owners” but the coming destruction of the entire Jewish administration of priests (“robes”) and Temple (“gold and silver”), which has lived “gloriously on the land” and is about to experience all the “woes” Jesus prophesied in Matthew 23 (See my Wisdom for Dissidents:The Epistle of James Through New Eyes [Athanasius Press, 2021], pp. 291-302).

What was near and how near?

I have singled out James as an example of how situating the letter in the context of the very early life of the church makes sense of the book as a whole, especially the passages that predict imminent judgment, that fulfills the prayers of the church for deliverance from the menace of Jerusalem’s persecution. We could analyze every New Testament epistle and discover that all the references to the near-to-hand world-changing event horizon are best understood as referring to the coming destruction on the apostate Jewish leadership and the old-world administration. A brief survey should suffice.

Paul’s burden in Romans is to explain “God’s righteousness” (Rom. 1:17), even though the chosen people are being severely pruned back and Gentiles grafted in (Rom. 9-11). He encourages them that their “rescue/salvation is nearer to us than when we first believed.” Indeed, it is “at hand” (13:11, 12). Paul promises them that the God of peace will shortly crush Satan under their feet (16:20).

The Corinthian church is told to wait “for the revealing of our Lord Jesus Christ, who will sustain you to the end, guiltless in the day of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor. 1:7, 8). The Spirit has gifted the Corinthian church to speak in “tongues” (non-Hebrew languages) to signal God’s judgment against the Jews (14:20-25), a danger Israel was warned of ages ago (Deut. 28:49; Isa. 28:11). In his second letter to the Corinthians Paul must defend his apostolic credentials against Jewish persecution and insist that the old, temporary Mosaic order was being “brought to an end” because of the new and better ministry of the Spirit (1 Cor. 3).

Galatians warns against the circumcision regime because the time of Jewish immaturity and subjection to the ABC’s of the old world is now coming to an end (Gal. 4).

Paul tells the Ephesians that the old bipolar division of mankind into Jews and Gentiles has served its purpose. The mystery of the Gospel “has brought to light for everyone what is the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things” (3:9).

In Philippians Paul warns against “the dogs. . . the evil doers . . . who mutilate the flesh” (3:2). They “walk as enemies of the cross of Christ. Their end is destruction. . . “ (3:18, 19). They should not be anxious because the Lord “is at hand” (4:5).

As I have pointed out earlier, Paul’s message in Colossians is that the “elements of the world” are no longer in force. These were “a shadow of the things to come, but the body/substance is Christ” (Col. 2:17). The whole old world administration with it’s angelic management, sabbath laws, food regulations, etc. is unravelling and should not influence the way Christians order their lives (2:126-23).

The two letters to the Thessalonians both use the near coming of the “Day of the Lord” to encourage and admonish the church. Paul identifies the enemies to be destroyed as those who are inflicting suffering on them:

. . . the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out, and displease God and oppose all mankind by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles that they might be saved—so as always to fill up the measure of their sins. But wrath has come upon them at last.

Paul describes for Timothy the misbehavior rampant in “the last days” (2 Tim. 3:1), a list designed to encourage Timothy and his church that what they are experience has been prophesied. They are living in the last days.

Hebrews is written “in these last days” (1:2) to warn believing Jews not to return to Judaism. Angels no longer manage the new world, Jesus does (Heb. 1-2). Jesus is greater than Moses and every Aaronic high priest (Heb 2-7). He is the mediator of a better covenant. The old one is now “obsolete. . . and what is becoming obsolete is growing old and ready to vanish away” (8:13).

Peter encourages his readers about how they are to live because “the end of all things is at hand” (1 Peter 4:7). It is “time for judgment to begin with the house of God” (4:17). And in his second letter he says that they “are waiting for and hastening the coming day of God” (2 Pet. 3:12, 14). And on that day the Lord will “come like a thief” and dismantle the old heavens in order to establish a “new heavens and a new earth” (3:10-14). Since this is something they are waiting for and hastening the astonishing description of this event is designed to impress on them the momentous significance of the coming move from the old to the new age.

According to the Apostle John, his readers should understand that “it is the last hour, and as you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come. Therefore, we know that it is the last hour” (1 John 2:18).

Jude expects his hearers to discern that the antagonism they are experiencing is evidence that they are living in the end times. “In the last time there will be scoffers, following their own ungodly passions” (Jude 18).

And then there’s Jesus’ revelation to the Apostle John in Revelation “to show to his servants the things that must soon take place” (Rev. 1:1).

In conclusion, evidently the Apostles expected the Lord to come in judgment soon. But they were not expecting the end of history, only the end of the old age and the beginning of a new one. This expectation fits nicely with Jesus’ prophecy of what would happen in that “generation” (Matt. 23:29-39; 24:34). If we date any of the NT books after A.D. 70 then it becomes very difficult to make sense of all the warnings and encouragements in the New Testament documents of a near-to-hand promise of the vindication of the church and the divine judgment on her enemies. Just to be clear—nothing I have said here should be understood as a denial that Jesus will return at the end of history for the final judgment. The judgment of the Jews and Jerusalem, like all historical judgments in Scripture, was a proleptic type of the Last Judgment.

I began this essay with an observation about why dating the New Testament books helps modern Christians appropriate what often seems alien and strange to them in these texts. I believe that helping folks understand when these books were written will help them appreciate why the content often seems foreign to their concerns. Knowing what was going on in the first century will help us all make the necessary adjustments when applying the New Testament to our day and age. The applications will sometimes be relatively straightforward. God is love. By grace you are saved through faith. The word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing. These seem straightforward enough. But even with these texts a knowledge of the circumstances into which they were given will help us fill out the richness of even comparatively simple sayings.

Jeff Meyers is pastor of Providence Reformed Presbyterian Church in St. Louis.

My contribution to this conversation will be a modest one, the perspective of a parish pastor who has preached and taught through all of the New Testament texts to ordinary church folks for 35 years. When parishioners ask questions about the dating of New Testament books they are usually asking because 1) they want to have some confidence in their authenticity, and therefore, their reliability and/or 2) they recognize that the Gospels, Acts, and the apostolic letters are very often addressing matters that at first glance seem to be foreign to modern Christian living.

So on the one hand, apologetic challenges often give rise to questions about evidence for the accuracy and trustworthiness of what has been recorded. How confident can we be that the Gospels reliably document the acts and words of Jesus? Did Paul really pen these letters attributed to him? If, for example, the Gospels were penned decades after the ministry of Jesus, after many decades of oral transmission, can we trust the truthfulness of what we read?

And on the other hand, so much of the New Testament is addressing concerns that at first seem alien to us in the modern world. Why all the talk about Jews and Gentiles, circumcision, food laws, sabbath regulations, sacrifices, priests, the land, and the temple? How does it all fit together? And what are we to learn from disputes that don’t seem to connect with challenges that we face today?

These two concerns are related. God reveals himself and his will for us by means of the situation of first century transition from the old world to the new. Jesus’ death, resurrection, ascension, and the out-pouring of the Holy Spirit inaugurated enormous changes, a ritual and social revolution, if you will. Dating these documents before the destruction of the Temple and the judgment against Jerusalem in A.D. 70 helps Christians understand the transitional situation addressed by the Apostles and enables us to make appropriate adjustments to understand how the narratives and letters apply to modern life.

Ralph Smith’s careful review and critique of Bernier’s Redating the New Testament helpfully addresses both common concerns. When I read Bernier’s book earlier this year, I spotted many of the concerns Smith has outlined. But he has courageously identified significant deficiencies in the way the academy has dealt with dating these documents and then proposes beneficial correctives. Before I offer my own contribution, let me highlight some of Smith’s more interesting points.

- There is no well-established consensus on dating these documents, especially the Gospels. Early dates have not been ruled out by present scholarship. Even the more liberal scholar John A.T. Robertson in his Redating the New Testament (1976) challenged the later dates so often assumed in post-Enlightenment academic research.

- Modern scholarship approaches questions about dating with theological and philosophical presuppositions that bracket traditional ecclesiastical convictions about the nature of these texts as divine revelation. This makes them susceptible to theories that place the New Testament documents later than the first century, often at the end of a long period of oral transmission, and composed as pseudepigrapha.

- Many scholars, including Bernier, fail to reckon with the decidedly Jewish persecution of the early church, especially before the latter half of the reign of Nero. The enemy of the nascent church in the New Testament is not Rome, but Jerusalem’s religious leaders. Roman officials are more often presented in a positive light in the Gospels and Acts, even acting as legal guardians to what they considered a Jewish sect. That changes in the later 60’s when Jewish and Roman persecutors align in their persecution of the church.

- If #3 is true, and can readily be established by a careful reading of the New Testament texts, then Bernier’s methodological approach of synchronization and contextualization situates the dating of these texts earlier in the first century that is commonly thought.

- A written account of Jesus’s teaching and ministry would have been needed very shortly after Pentecost. The proclamation of Jesus as the promised Messiah that began with the preaching of Peter and the other Apostles demanded a written account of the fulfilment of the prophecies contained in the Jewish Scripture. After all, the Jews were “people of the book,” as Smith notes.

- Smith’s summary of the disciple Matthew’s (Levi’s) qualifications for writing such an account are compelling. As a tax collector, Matthew would have been something of a bean counter and the ideal disciple to pen the first comprehensive account of how Jesus fulfilled all the narratives and predictions of the prophetic Scriptures. The early church needed a narrative that grounded all of Jesus’ ministry in the “it stands written” revelation of Israel’s prophetic tradition.

- Mark’s Gospel, grounded in Peter’s apostolic perspective, builds on Matthew. And I would argue Mark writes his account in the early 40s to comfort and instruct the increasingly persecuted church by emphasizing Jesus as the greater son of David, a royal figure who has been anointed king, but must keep his identify secret until he accomplishes his self-sacrificial death on the cross. The centurion is the first to identify him as the “Son of God” (a royal, Davidic title) when he observes how Jesus “breathed his last” (Mark. 15:39).

- The dating of Luke’s Gospel is less controversial (50s) for obvious reasons. Luke has clearly been influenced by Paul’s ministry, writing to the Gentile convert Theophilus (which may be a cipher for the whole Gentile Christian portion of the emerging church). And his second volume is completed before Paul’s trial in Rome (before A.D. 62).

- Smith’s criticism of Bernier and others who fail to address the importance of Jesus’ Olivet Discourse for establishing an early date for all of the New Testament books deserves careful attention. Not only does Jesus predict the judgment on Jerusalem and the “end of the age,” in the Synoptic Gospels, but Acts and all the New Testament letters are written with the expectation of an imminent judgment. The judgment on Jerusalem and the Temple signals the passing away of the old age, which is why the period between AD 30 and 70 can be called the last or latter days (Acts 2:17; Heb. 1:1-2; James 5:1-3; 1 John 2:18), the last or end times (1 Pet. 1:20; 2 Pet. 2:20), the end of the age(s) (Heb. 9:26), and the last hour (1 John 2:18).

Moving from the Old to the New

Perhaps this last point (#9) can be expanded a bit. At the end of his contribution in the conversation Mark Garcia writes,

A further, related nagging question in reading Smith’s piece is the fact that, outside his proposed reading of the Discourse, the New Testament rather consistently points to the passion and resurrection/ascension of Christ as his ushering in of the new world, and not the events of AD 70. Though I appreciate this pulls us into a range of arguments I can’t explore here, I would like to hear more of why Smith connects that new world to AD 70 as he does (p. 12) in comparison with the Apostolic focus on the passion and resurrection/ascension.

I’d like to try to help answer this question. There is no need to place the death and resurrection/ascension of Christ in competition with the reality of a new world connected with the judgment of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 AD. They are not at odds. In the Apostolic writings, they are connected. Jesus inaugurated a new world when he ascended into heaven and poured out his Spirit on the embryonic church. He got things started, but there was still much left to do—the second offer of repentance to the Jews, for example. John the baptizer warned the crowds who came to the Jordan river of an imminent, fiery judgment unless they repented (Luke 3:1-17).

“Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. . .” (Luke 3:9).

The one mightier that John is coming and “his winnowing fork is in his hand to clear his threshing floor and to gather his wheat into his barn, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (Luke 3:16, 17).

Jesus then begins his ministry by proclaiming repentance “for the kingdom of heaven/God is at hand.” Too often preachers and commentators miss how many times Jesus warns of a coming judgment. It would take too much space to reference all these prophetic warnings recorded by the Gospel writers. N.T. Wright’s gives extensive coverage in chapter 8 of his Jesus and the Victory of God (pp. 320-368). His observation is only too true:

The next comment ought to be unnecessary, but misunderstanding has been so long-lasting here that perhaps it is as well to be clear. The warnings already mentioned, and those about to be discussed, are manifestly and obviously, within their historical context, warnings about a coming national disaster, involving the destruction by Rome of the nation, the city, and the Temple. The story of judgment and vindication which Jesus told is very much like the story told by the prophet Jeremiah, invoking the categories of cosmic disaster in order to invest the coming socio-political disaster with its full theological significance (p. 323, emphasis mine).

On Pentecost Peter cites Joel 2, which prophesied both the Spirit’s outpouring and the coming “day of the Lord” (Acts 2:17-21). Joel describes that day with language that reminds us of Jesus’ many warnings of Judgment, especially the Olivet Discourse. At Pentecost the Apostles, empowered by the Holy Spirit, again warn the Jews—who are now guilty of crucifying their Messiah—of the coming Day of the Lord that can only be avoided by repentance and confession of Jesus as resurrected and ascended Lord (Acts 2:22-41).

The Holy Spirit speaking through the Apostles is the gracious “second witness” given by Jesus to the Jewish people. Unbelieving “words spoken against the Son of Man” during Jesus’ earthly ministry could be forgiven but. . .

. . . the one who blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven. And when they bring you [the Apostles] before the synagogues and the rulers and the authorities, do not be anxious about how you should defend yourself or what you should say, for the Holy Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say.” (Luke 12:8-12)

This gracious second witness of the Spirit to the Jews begins ca. A.D. 30 at Pentecost. Just as Jesus promised, the Apostles are given what to speak before the Jewish leaders and people. The book of Acts chronicles this in some detail. Even Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles, always goes “to the Jews first,” visiting the synagogues in the diaspora to reason with them from the Scriptures that Jesus was the Messiah. I hardly need to cite passages since this is so well known. But what is often missed is the significance of this forty-year time of testing (from AD 30 to 70) for our understanding of the dating of Gospels and the Apostolic epistles.

Would the Jews follow Joshua Messiah into the new age, the new world he inaugurated by his death, resurrection, ascension, and session as King at the right hand of his Father? Many did, but not all. At the end of Acts, Paul is in Rome still proclaiming to the Jews “the kingdom of God and trying to convince them about Jesus” (Acts 26:23). But they are recalcitrant. So quoting the prophecy of Isaiah 6:9-10 (the same passage Jesus used to explain why he spoke in parables), Paul alters his strategy. He has done his duty. The Jews have heard and refused to believe. They have sealed their fate. The forty years of grace are over.

When Jesus met with the Apostles on the day of his ascension, they thought that the resurrected Jesus would immediately “restore the kingdom to Israel” (Acts 1:6). This misunderstanding was not instantly corrected by Jesus. Why? Because their understanding of the nature and extent of Jesus kingdom needed to be formed by their experience of the unrepentance and vicious persecution of the Jewish authorities recorded for us in the book of Acts. Near the end of this history the Jerusalem Jews are so hardened against the Jesus and his church that they conspire to assassinate Paul, the chief priests and elders conspiring together in the plot (Acts 23:12-15). They are fulfilling Jesus’ prophecy in Matthew 23. Everything he predicted is happening during the apostolic age, and the judgment, therefore, is coming upon that generation.

“Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you build the tombs of the prophets and decorate the monuments of the righteous, saying, ‘If we had lived in the days of our fathers, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.’ Thus you witness against yourselves that you are sons of those who murdered the prophets. Fill up, then, the measure of your fathers. You serpents, you brood of vipers, how are you to escape being sentenced to hell? Therefore I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your synagogues and persecute from town to town, so that on you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of innocent Abel to the blood of Zechariah the son of Barachiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. Truly, I say to you, all these things will come upon this generation.” (Matt. 23:29-36)

What does this have to do with dating the books of the New Testament? And how does dating the books of the New Testament before the judgment against Jerusalem affect our understanding of their message? The Gospels and the all the epistles cannot be fully understood apart from the recognition that Jesus’ parable of the tenants of his vineyard is being fulfilled. Speaking to the chief priests, elders, and Pharisees, Jesus prophesies at the conclusion of that parable:

“Therefore I tell you, the kingdom of God will be taken from you and given to a people producing its fruits. And the one who falls on this stone will be broken to pieces; and when it falls on anyone, it will crush him” (Matt. 21:43, 44).

The New Testament everywhere testifies of this momentous change, the transition from a Jewish-centered, Temple-oriented socio-religious world to the new kingdom of the risen Lord Jesus. Even though the Temple is still standing during the Apostolic age, it has been side-lined by the new Spirit-indwelled temple of living stones (Acts 2; 1 Cor. 3), and will be destroyed, not one stone left upon another (Matt. 24:2). The old administration symbolized by the Decalogue was “written and engraved in stones,” and as glorious as it was, was nevertheless a “ministry of death” and was being supplanted by a more glorious reality.

“. . . what once had glory has come to have no glory at all, because of the glory that surpasses it. For if what was being brought to an end came with glory, much more will what is permanent have glory” (2 Cor. 3: 10, 11).

What Jesus had accomplished in his glorified, resurrected flesh was nothing short of a new creation.

“Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come” (2 Cor. 5:17).

“For neither circumcision counts for anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creation” (Gal. 6:15)

Those two references are not about an individual’s new heart (other passages attest to something like that). Rather, they testify to the newly fashioned, historical reality that Jesus has brought to pass; a reality oriented around his glorified Person that was inexorably changing the entire old way of life.

That old creation and its old way of life was characterized by the Apostle Paul as ta stoicheia tou kosmou, variously translated as “the elements of the world” or “the elementary principles of the world.”

I mean that the heir, as long as he is a child, is no different from a slave, though he is the owner of everything, but he is under guardians and managers until the date set by his father. In the same way we also, when we were children, were enslaved to the elementary principles of the world. But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God. Formerly, when you did not know God, you were enslaved to those that by nature are not gods. But now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God, how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world, whose slaves you want to be once more? You observe days and months and seasons and years! I am afraid I may have labored over you in vain (Gal. 4:1-9).

A careful reading of that passage will reveal that both the Jews (Paul’s use of “we”) and the Gentiles (addressing the Galatians with “you”) were both, before Christ, subject to immature bondage under “the elements.” Before Jesus ushed in the new age, everyone lived under the stoicheia. Although somewhat different for Jews and Greeks, the stoicheic life was a cultural and social world characterized by angelic management (Gal. 4:3; Col. 2:18; 1 Cor. 10:20; Heb. 1:1-14), purity laws (Acts 10; I Tim. 4:3; Col. 2:20-23), geographically defined zones of holiness (I Cor. 3:17; Heb. 9-10), stone temples (I Cor. 3:17; Eph. 2:21; 1 Pet. 2:5), bloody animal sacrifices (Heb. 9-10), a binary division of mankind into Jews and Gentiles (Eph. 2:11-22), sabbath regulations (Col. 2:16), a genealogical priesthood (1 Pet. 2:9; Heb. 7-8; Rev. 5:10), and more. (For a detailed analysis see Peter Leithart’s Delivered from the Elements [Intervarsity Press, 2016].) All of this was passing away. Jesus was not merely introducing a new “religion” of individual salvation, he overhauled the entire system. That stoicheic system was unravelling during the apostolic age. The judgment on Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in AD 70 would be the symbolic end of the old age.

It would be difficult to overestimate the hermeneutical significance of the transitional situation the apostolic writers addressed. It would be like some scholar five hundred years from now trying to make sense of the texts, letters, and the content of other forms of communication in 2020 without knowing about the COVID19 virus, thinking that he was reading texts written in 2045. Maybe that’s an unhelpful analogy because it’s so obvious to us. Nevertheless, what was obvious to the Apostles was what needed to be understood by Jews and Gentiles alike—that Jesus’ death, resurrection, and ascension had ushered in a new age. The old age with its central sanctuary, holy land, holy city, priesthood, food taboos, sabbath festivals, sacrificial system, circumcision, genealogies, and more—that entire way of structuring the ritual and social lives of Jews and Gentiles had served its purpose and was now passing away.

I have used this chart with students to help them visualize the transitional nature of the Apostolic age and appreciate the content of the Gospels and Epistles. Like every chart, it has its limitations.

How Early is Too Early?

I would like briefly to address another concern. In research for my James commentary, especially the dating of that letter, I found Bible scholars making unjustifiable judgments about “how early” the letter might have been written. Almost every commentator, even conservative Evangelical scholars, only have one big argument against the authorship of the Apostle James before his death at the hands of Herod Agrippa I in AD 44 (Acts 12:1-2)—it would be “too early.” Apparently for most scholars, a letter like this could not have been written so early in the apostolic age. Commentators repeatedly assure us of the “improbability” of dating this epistle during the life of James the Apostle. Peter Davids’s dismissal is representative: “James the son of Zebedee probably died too early to leave any literary remains.” He adds, “Acts 12 indicates that he died before AD 44, ruling out the probability, although not the possibility, of his writing the epistle” (The Epistle of James [Eerdmans, 1982], p. 6). Why is an early date so improbable? Nobody gives definitive reasons for this assessment. It’s just too early, they say. Motyer, however, gives us an honest appraisal:

It is usually thought that James son of Zebedee was martyred at too early a date (AD 44) for him to have been the author of the letter [of James]. Even this, however, cannot be maintained for certain. Nothing in the letter absolutely forbids a date as early as James the son of Zebedee, and certainly the arguments proposed for later dates lack impressiveness (The Message of James [InterVarsity Press, 1985], p. 18).

I suspect that behind the trepidation to date this epistle, as well as any of the Gospel narratives, within the first decade of the life of the church, is the assumption that the teachings of Jesus and the supervision of the fledgling Christian community was at first accomplished by means of oral communication alone. Before anything was written down, the stories and the instruction had to be passed on by means of oral tradition. That may have been true in Hellenistic cultures. But when it comes to the early Christian community we are dealing with Jews, a literary, bookish people. It is very difficult to believe that men who were convinced the promised Messiah had come—the one foretold in all their sacred writings and explicitly prophesied in the prophetic books of the Hebrew Scriptures—would wait decades before recording in writing such momentous events.

The fact that James is a circular letter makes the charge of it being “too early” even more questionable. After all, the epistles of the New Testament are all written by Paul, Peter, or John straightaway to deal with immediate problems and challenges in the churches. There was no intermediate oral communication. Even if there was personal, oral communication by means of representatives sent by these Apostles to the various churches, they more often than not carried with them letters to be read in the assembly (e.g., 1 Thess. 5:27). These are the letters we have designated the “New Testament Epistles,” and not one of them was written a decade or more after the events that precipitated the need for these written messages.

Given that James identifies the recipients of this letter (1:1, “to the twelve tribes in the dispersion”), we should consider the urgency of the communication to these Christians banished from Jerusalem by the persecuting leaders of the church. If the crisis referred to here is indeed the forced exile of Jewish Christians from Jerusalem, as recorded for us in Acts 8:1 and Acts 11:19, then it seems quite reasonable to believe that the Apostle James wrote this letter soon after their banishment to challenge these Jewish Christian believers. It would make sense to distribute a circular letter like this while these disciples are still separated from Jerusalem. But a dozen years or so after the initial banishment, after the death of the Apostle James (Acts 12:2), when James the brother of Jesus seems to have taken the leadership of the Jerusalem Christian community, the situation had changed. There appears to be a flourishing community again in Jerusalem (Acts 12:17; 15:1-21). If that exile from Jerusalem took place in the aftermath of Stephen’s martyrdom, a year or so after Pentecost, and only the Apostles remained in the city, then dating the letter sometime in the early to mid 30s makes more sense.

There are other compelling reasons to believe that James’s letter was composed very early in the life of the church. I have detailed those reasons in my commentary. I have used James as an example of the way many in academia too readily dismiss earlier dates for the composition of New Testament documents.

One other observation. Surely if Jesus commissioned the Twelve to be his “witnesses” and empowered them with the Holy Spirit who would guide them into all truth (John 14:25-26; 16:12-14), we would expect them to begin the work of testifying to Jesus immediately, and not just by preaching, but also by making and distributing written documents establishing Jesus as the promised Messiah. Composing the founding documents of the Messianic age would have been a large part of their vocation as Apostles. This is why Luke calls them “servants of the word”:

Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught (Luke 1:1-4).

I believe they took this mandate so seriously that they had to delegate authority to other men to distribute food to widows during the controversy narrated in Acts 6. As important as providing for the welfare of the widows in both the Hebrew and Hellenstic communities might have been, their calling as servants of the Word took precedence.

And the twelve summoned the full number of the disciples and said, “It is not right that we should give up the word of God to serve tables. Therefore, brothers, pick out from among you seven men of good repute, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we will appoint to this duty. But we will devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word.”

This story is often read by Presbyterians as a justification for pastors to concentrate on the preaching of the Word and an authorization to delegate other responsibilities to “deacons.” But the word “preaching” (ESV) is not in the original. The Apostles simply say, “It is not right for us to give up the Word of God to serve tables” (v. 2). Of course, it is appropriate to use this passage to illustrate the advisability of delegating authority in church communities. But the Apostles here in Acts 6 are not simply “ministers”—preachers that need to have their schedules free from distractions so they can prepare for sermons and pray. What if the Apostles, not wanting to “give up the Word of God,” meant that they were so engaged with collaborating to produce the written document (Matthew) that would provide a foundation for the fledgling Christian community that they could not let even widow care interfere with such a momentous project? I think the connection with Luke 1:1-4 makes that interpretation likely.

Back to my research on James’s epistle. By identifying himself in verse 1 as a “servant” (doulos) of God and the Lord Jesus Christ,” James would appear to be signaling his association with the other apostolic “servants of the word” (Luke 1:2). Unless there are some very good reasons to think otherwise, it seems reasonable to begin with the assumption that the author is indeed James the Apostle.

There are other compelling reasons to believe that epistle of James was composed very early in the life of the church. Many commentators have noted that 1) there is a decidedly Jewish flavor to the vocabulary and content, 2) James does not touch on common debates and controversies which occupied the apostolic church in later decades, 3) there is a “primitiveness to James’s theological framework . . . which is exactly what we would expect of a very early Christian writing” (Dan. G. McCartney, James [Baker Academic, 2009], p. 15), and 4) the letter is full of clear allusions to Matthew’s Gospel, and the correspondences to the Sermon on the Mount are well documented. This last feature of James fits with the post-apostolic church’s understanding of the relative order of the Synoptic Gospel accounts—that the canonical order is the order in which the Gospel narratives were written. Matthew’s gospel was either already composed and beginning to circulate or was in the process of being written, and James, as a member of the apostolic brotherhood, had some access to Matthew’s material. McCartney comes to a similar conclusion:

It is as though James is imbued with the wisdom teaching of Jesus, but not in the written form in which we now find it. All this points to a time quite early in the life of the church, prior to the theological reflections of Paul, prior to the circulation of the Gospels, and prior to the authors of Hebrews, 1 Peter, and the Johannine materials, or at least prior to the time when these other writings began to have widespread and determinative influence . . . James represents a state of Christian thinking that has not yet been determined by them, and hence is logically prior. (p. 8)

I would add that James is not merely grounding his admonitions on the “wisdom teaching” of Jesus, but he is also giving the persecuted community hope based on Jesus’ repeated prophetic denunciations of the failed leadership of the Jewish authorities (1:9-11; 2:6-7; 5:1-6; cf. Matt. 23) and the coming destruction of the Temple (Matt. 24). The exiled Church’s theocratically rich oppressors will be judged shortly, “for the coming of the Lord is near” (5:8). We are back to the hermeneutical significance of dating the New Testament documents before AD. 70. James 5 is not describing a generic judgment on rich “plantation owners” but the coming destruction of the entire Jewish administration of priests (“robes”) and Temple (“gold and silver”), which has lived “gloriously on the land” and is about to experience all the “woes” Jesus prophesied in Matthew 23 (See my Wisdom for Dissidents:The Epistle of James Through New Eyes [Athanasius Press, 2021], pp. 291-302).

What was near and how near?

I have singled out James as an example of how situating the letter in the context of the very early life of the church makes sense of the book as a whole, especially the passages that predict imminent judgment, that fulfills the prayers of the church for deliverance from the menace of Jerusalem’s persecution. We could analyze every New Testament epistle and discover that all the references to the near-to-hand world-changing event horizon are best understood as referring to the coming destruction on the apostate Jewish leadership and the old-world administration. A brief survey should suffice.

Paul’s burden in Romans is to explain “God’s righteousness” (Rom. 1:17), even though the chosen people are being severely pruned back and Gentiles grafted in (Rom. 9-11). He encourages them that their “rescue/salvation is nearer to us than when we first believed.” Indeed, it is “at hand” (13:11, 12). Paul promises them that the God of peace will shortly crush Satan under their feet (16:20).

The Corinthian church is told to wait “for the revealing of our Lord Jesus Christ, who will sustain you to the end, guiltless in the day of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor. 1:7, 8). The Spirit has gifted the Corinthian church to speak in “tongues” (non-Hebrew languages) to signal God’s judgment against the Jews (14:20-25), a danger Israel was warned of ages ago (Deut. 28:49; Isa. 28:11). In his second letter to the Corinthians Paul must defend his apostolic credentials against Jewish persecution and insist that the old, temporary Mosaic order was being “brought to an end” because of the new and better ministry of the Spirit (1 Cor. 3).

Galatians warns against the circumcision regime because the time of Jewish immaturity and subjection to the ABC’s of the old world is now coming to an end (Gal. 4).

Paul tells the Ephesians that the old bipolar division of mankind into Jews and Gentiles has served its purpose. The mystery of the Gospel “has brought to light for everyone what is the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things” (3:9).

In Philippians Paul warns against “the dogs. . . the evil doers . . . who mutilate the flesh” (3:2). They “walk as enemies of the cross of Christ. Their end is destruction. . . “ (3:18, 19). They should not be anxious because the Lord “is at hand” (4:5).

As I have pointed out earlier, Paul’s message in Colossians is that the “elements of the world” are no longer in force. These were “a shadow of the things to come, but the body/substance is Christ” (Col. 2:17). The whole old world administration with it’s angelic management, sabbath laws, food regulations, etc. is unravelling and should not influence the way Christians order their lives (2:126-23).

The two letters to the Thessalonians both use the near coming of the “Day of the Lord” to encourage and admonish the church. Paul identifies the enemies to be destroyed as those who are inflicting suffering on them:

. . . the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out, and displease God and oppose all mankind by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles that they might be saved—so as always to fill up the measure of their sins. But wrath has come upon them at last.

Paul describes for Timothy the misbehavior rampant in “the last days” (2 Tim. 3:1), a list designed to encourage Timothy and his church that what they are experience has been prophesied. They are living in the last days.

Hebrews is written “in these last days” (1:2) to warn believing Jews not to return to Judaism. Angels no longer manage the new world, Jesus does (Heb. 1-2). Jesus is greater than Moses and every Aaronic high priest (Heb 2-7). He is the mediator of a better covenant. The old one is now “obsolete. . . and what is becoming obsolete is growing old and ready to vanish away” (8:13).

Peter encourages his readers about how they are to live because “the end of all things is at hand” (1 Peter 4:7). It is “time for judgment to begin with the house of God” (4:17). And in his second letter he says that they “are waiting for and hastening the coming day of God” (2 Pet. 3:12, 14). And on that day the Lord will “come like a thief” and dismantle the old heavens in order to establish a “new heavens and a new earth” (3:10-14). Since this is something they are waiting for and hastening the astonishing description of this event is designed to impress on them the momentous significance of the coming move from the old to the new age.

According to the Apostle John, his readers should understand that “it is the last hour, and as you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come. Therefore, we know that it is the last hour” (1 John 2:18).

Jude expects his hearers to discern that the antagonism they are experiencing is evidence that they are living in the end times. “In the last time there will be scoffers, following their own ungodly passions” (Jude 18).

And then there’s Jesus’ revelation to the Apostle John in Revelation “to show to his servants the things that must soon take place” (Rev. 1:1).

In conclusion, evidently the Apostles expected the Lord to come in judgment soon. But they were not expecting the end of history, only the end of the old age and the beginning of a new one. This expectation fits nicely with Jesus’ prophecy of what would happen in that “generation” (Matt. 23:29-39; 24:34). If we date any of the NT books after A.D. 70 then it becomes very difficult to make sense of all the warnings and encouragements in the New Testament documents of a near-to-hand promise of the vindication of the church and the divine judgment on her enemies. Just to be clear—nothing I have said here should be understood as a denial that Jesus will return at the end of history for the final judgment. The judgment of the Jews and Jerusalem, like all historical judgments in Scripture, was a proleptic type of the Last Judgment.

I began this essay with an observation about why dating the New Testament books helps modern Christians appropriate what often seems alien and strange to them in these texts. I believe that helping folks understand when these books were written will help them appreciate why the content often seems foreign to their concerns. Knowing what was going on in the first century will help us all make the necessary adjustments when applying the New Testament to our day and age. The applications will sometimes be relatively straightforward. God is love. By grace you are saved through faith. The word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing. These seem straightforward enough. But even with these texts a knowledge of the circumstances into which they were given will help us fill out the richness of even comparatively simple sayings.

Jeff Meyers is pastor of Providence Reformed Presbyterian Church in St. Louis.

-->