Abraham’s life in Genesis is a series of trials. He travels hundreds of miles from his family into a new land, flees from a famine into the hands of a king who takes his wife, and after returning, has to rescue his brother from a war. He’s involved with two disputes between Sarai and Hagar, two property disputes (with Lot and with Abimelech), and finally, after all this, God demands that Abraham sacrifice his son, the son he had been given only after 25 years of waiting.

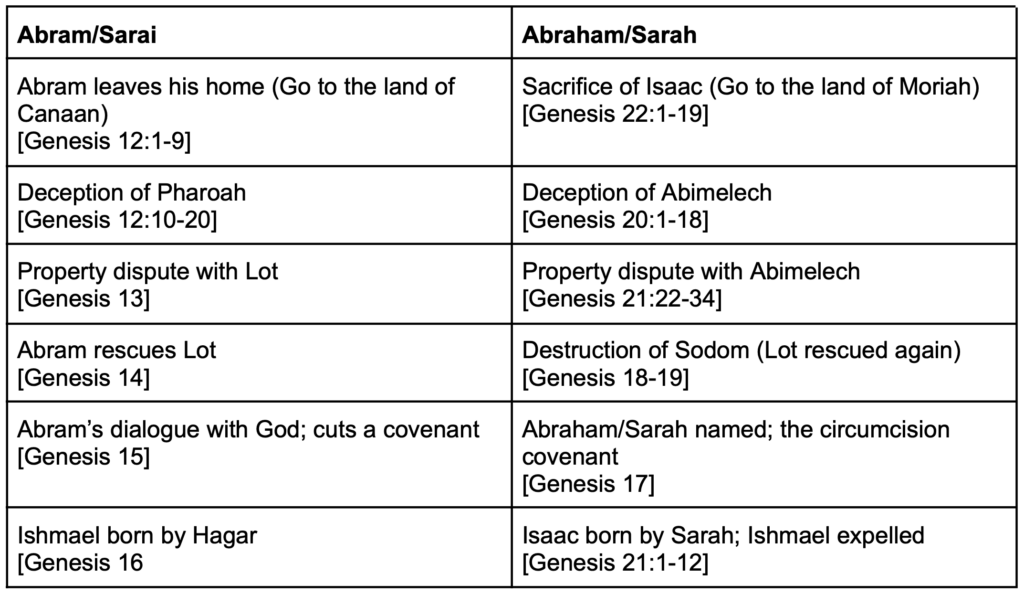

I want to make two points about these trials. First, that there are 12, organized in six pairs, centered around Abraham’s name change. Second, in each pair, the second trial is in some way an escalation over the first. As Abraham’s life unfolds, he is being trained up through a series of greater trials, and he is rewarded with greater promises and responsibilities.

Here are Abraham’s twelve trials, arranged in pairs.

Go to the Land of Canaan/Moriah

The first pair forms an inclusio around Abraham’s full set of twelve trials. Wenham1, Waltke2, and Everett Fox3 all recognize the parallel between these passages. In both, God commands Abraham to leave his home to go to a land (12:1 and 22:2). Waltke points out that the phrase lek l’ka, translated “go”, only occurs in these two verses in the entire Old Testament.4

In both cases, God asks Abraham to do something absurd. In the first trial, God promises to make a great nation of Abram, if he only leaves his land and family. But nations are lands and families (Genesis 10). In order to become a great nation and have a great name, Abram has to forsake his nation and name. The second trial is even worse; Abraham must sacrifice the son God has finally given him.

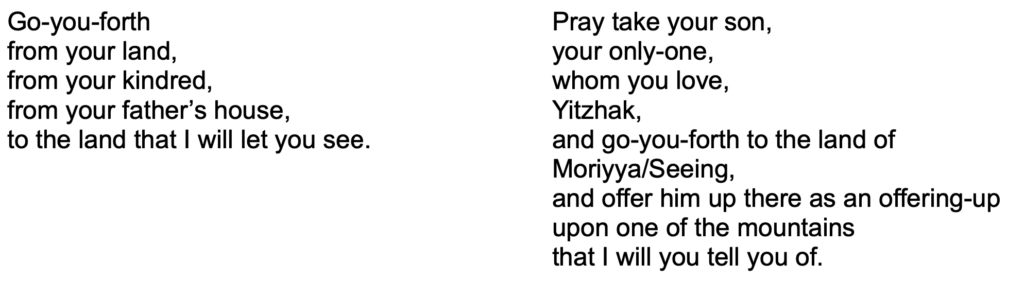

Both passages emphasize the absurdity with drawn-out, dramatic phrases leading up to God’s command. Here are Genesis 12:1 and 22:2 side-by-side, using Everett Fox’s translation:5

In both cases, Abraham immediately obeys without any dialogue or question. This isn’t a big surprise in chapter 12 – at that point in Genesis, the only dialogues with God had been in contexts of judgment (Adam and Eve; Cain). But every chapter from Genesis 15 to 21 includes someone speaking back and forth with God, Abraham himself in three cases (15, 17, 18). When God speaks to Abraham in chapter 22, we expect him to say something back. Instead, all we get is “Here I am” in verse 1, and then silence after God’s shocking command. Abraham is back to immediate and silent obedience, as in chapter 12.

The escalation in the second trial is clear; the first test is difficult, but the second is gut-wrenching. After waiting 25 years for God’s promise to be fulfilled, God commands that Abraham give up his own son by his own hands. And Abraham does, without a word of questioning. Abraham’s reward is greater, too. In 22:16-18, the verbs are doubled: “blessing I will bless” and “multiplying I will multiply”. The promise “your seed will possess the gate of his enemies” is also new, only appearing in chapter 22.6

Deception of Pharaoh/Abimelech

The second pair is a clear repetition. In both cases, Abraham is journeying toward the desert (12:9; 20:1) when they enter a powerful king’s land and claim to be brother and sister. Sarah is taken in, God protects her, and when the deception is found out, the ruler confronts them. In both cases, Abraham and Sarah come out much wealthier.

There is also contrast, though. With Pharoah, Abraham is entirely passive, aside from the deception itself. When Pharoah discovers the deception, he casts Abraham out of Egypt harshly, without a word of response from Abraham.

With Abimelech, though, Abraham plays a more important role. When Abimelech confronts him, Abraham responds (20:11-13). After Sarah is restored, Abraham also prays to God to heal Abimelech (20:17). Not only this, but instead of kicking Abraham out, like Pharoah, Abimelech invites Abraham to stay in the land, “wherever seems good in your eyes” (20:15).

Why the change? Because Abraham is a prophet (20:7). This might seem like a minor point at first glance – the Bible is full of prophets – but this is the first time anyone is called a prophet in the Bible. Abraham’s stature has grown; he now dialogues with powerful kings and even intercedes for them with God. He lives in good land, at peace with and respected by the ruler.

Property Dispute with Lot/Abimelech

In Abram’s third trial, he has to resolve a dispute between his herdsman and Lot’s. In the paired trial, Abraham does the same in a dispute with Abimelech’s servants over a well. In both, Abraham resolves the dispute peacefully, and afterwards he worships God at a tree (13:18; 21:33).

Neither of these stories seem particularly important – the first seems mostly there to explain why Lot ends up in Sodom, and the second feels especially inconsequential stuck between the birth and the offering of Isaac. They’re important, though, because of what doesn’t happen: there’s no violence.

Remember: Genesis is full of violence. Cain kills Abel. Lamech was a murderer. The earth was so full of violence God wiped out all of mankind in a flood. In the aftermath, Nimrod, a mighty hunter, founds a kingdom. The men of Sodom are violent. Abraham has to rescue Lot from a war between nine kings. Like it always has been, the land is still full of violence.

But Abram resists this. Instead of killing his brother, like Cain, he appeals to Lot: “we are brothers” (13:8). Abram is a peaceful brother, not a murderous one. For that, God rewards him with a renewed promise (13:14-17), and Abram sets up a garden-altar to worship God (13:18).

The dispute with Abimelech repeats the same, but in a greater way. Abraham is now navigating a dispute with a king, which means a nation, not just his brother. Remember, though: nations are brothers – the nations are established in Genesis 10 as a great family tree. Peace between nations is just peace between brothers at a larger scale. In this sense, Abraham, again, proves to be a peaceful nation/brother, and in the end, he’s worshiping God at peace at a garden-altar.

Rescue of Lot

In both these trials, Abraham rescues Lot from death. The stories are quite a bit different, but they align in a few surprising details. In both, Abraham is confronted at the terebinths of Mamre (14:13-14; 18:1). In the first, he is in covenant with three brothers, who help him rescue Lot (14:13). In the second, he is in covenant with God (17), and he converses with three men (18:1), angels sent by God, who rescue Lot. In the first story, a priest of God feeds Abram (14:19-20); in the second, Abraham feeds the angels of God.

In the second trial, Abraham is welcomed into the council of God to join in the judgment of Sodom. Though he’s not called a prophet until chapter 20, he’s playing the part at this point, interceding with God for the righteous in Sodom. If Abraham is to be a mighty nation, blessing all other nations, then he and his household will have to do righteousness and justice (18:18-19). So God welcomes him into a dialogue about justice; He is training Abraham. Abraham’s intercession has a real impact, like it does with Abimelech. Lot is rescued because God remembered Abraham (19:29).

Covenant Cutting

In both Genesis 15 and 17, God makes a covenant with Abraham. The structure of both scenes is similar: God appears to Abraham and reinforces his promise. In both, Abraham speaks back to God, questioning Him about the promise (15:2-3, 8; 17:17-18), and God responds. In both, God makes a promise, and that promise is confirmed with a cutting of flesh – a sacrifice in chapter 15 and circumcision in chapter 17.

The covenant in 17 is both a greater trial and a greater reward. In chapter 15, Abram is concerned that he has no heir, and God reassures Him with a promise and a covenant. Afterwards, Hagar bears Ishmael to Abram. By the time we reach chapter 17, Ishmael is 13 years old (16:16-17:1). As far as Abram knows, Ishmael is the promised seed, growing into a man, and ready to be his heir.

Through the first half of God’s speech to Abram, nothing about this is called into question. God gives Abram a new name, Abraham, and he makes an even greater promise: now Abraham will be a father of many nations (17:5), and he will be “exceedingly many” (17:2) and “exceedingly fruitful” (17:6). For this, Abraham has a new responsibility: circumcision (17:9-14).

It’s not until 17:16 that God tells Abraham the news: Ishmael isn’t the heir. It’s been 24 years since he entered the land, but he’ll have to wait even longer. Abraham appeals (17:17-18), but God says no, he’ll have another son, this time through Sarah, and his name will be Isaac (17:19).

Now in a greater covenant with a greater promise, Abraham endures another trial of faith, trusting God to give him his son through his barren wife. He obeys immediately, circumcising his entire household “on that same day” (17:23).

Sarah and Hagar

In the last pair of trials, Abraham judges a dispute between Sarah and Hagar. In both scenes, Sarah appeals to Abraham, and Abraham takes her side – in the first case, reinforcing her authority over Hagar, and in the second, sending Hagar and Ishmael away to preserve Isaac’s claim as true heir. In both scenes, Hagar departs from Abraham, meets an angel of God in the wilderness, and receives a promise from God about Ishmael.

The escalation in the second scene is clear: in the first, Ishmael is born to Hagar. In the second, Isaac is born to Sarah. Finally, God has given Abraham his seed by Sarah, and His promise is fulfilled.

There’s another growth in this pair of scenes, though, this time with Sarah. In chapter 16, Abram “listened to the voice of Sarai” (16:2). As Wenham points out, the language here hearkens back to Genesis 3.7 16:2 uses the same language as Genesis 3:17, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife”. And the language in 16:3-4 is similar to 3:6-7. In both cases, the woman “took… and gave…” to her husband. In both cases, after the man receives the gift (eats the fruit/goes into Hagar), the passage calls attention to sight. In the first, Adam and Eve’s eyes are opened, they realize they are naked, and they sew fig leaves. In the second, Hagar sees that she has conceived and despises Sarai.

In Genesis 16, then, Abram and Sarai go through a sort of fall. They grow impatient, Abram listens to Sarai, and trouble comes. Genesis 21 is quite different. Sarah appeals to Abraham to cast out Hagar and Ishmael, and this time, God steps in and tells Abraham “all that Sarah says to you, listen to her voice” (21:12). Sarah is right, and God is siding with her. Sarah is now a wise helper and adviser to Abraham, helping him avoid a growing dispute between Ishmael and Isaac.

Abraham and Sarah do not come to us fully formed at the start of their story; God shapes them through decades of trials so they can mature into the roles He has for them. By the end, Abraham has grown into a faithful prophet, interceding for the righteous and bringing peace wherever he travels, and he has become a faithful father, teaching justice to the generations to come. And Sarah has grown into a wise partner to Abraham, bringing forth their son, the promised seed, and she is a faithful mother to Isaac, interceding for him to ensure God’s promise to him is fulfilled.

Donald Linnemeyer is a software engineer living in Galveston, TX.

Notes:

- G. J. Wenham, Genesis 16-50, Volume 2 (Zondervan, 2000), 100.

↩︎ - Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan, 2001), 301. ↩︎

- Everett Fox, The Five Books of Moses (Schocken Books, 1983), 92. ↩︎

- Weltke, 301.

↩︎ - Fox, 92. He points out the the strong parallels between these two passages in his comments on chapter 22.

↩︎ - There is also a shift from “in you all the families of the ‘adamah/soil will be blessed” to “in your seed all the nations of the ‘erets/earth will be blessed”. At the very least, this is a shift of focus toward the future – “you” to “your seed”. ↩︎

- Wenham, 7-8. ↩︎