Matthew 13 is about secrets. In this chapter, Jesus teaches eight parables and tells the disciples that they reveal the secrets of the kingdom (13:11). And much like Samson who both tells riddles and is himself a riddle that the reader must solve, so Jesus not only tells secrets but Matthew has made the chapter itself a secret.

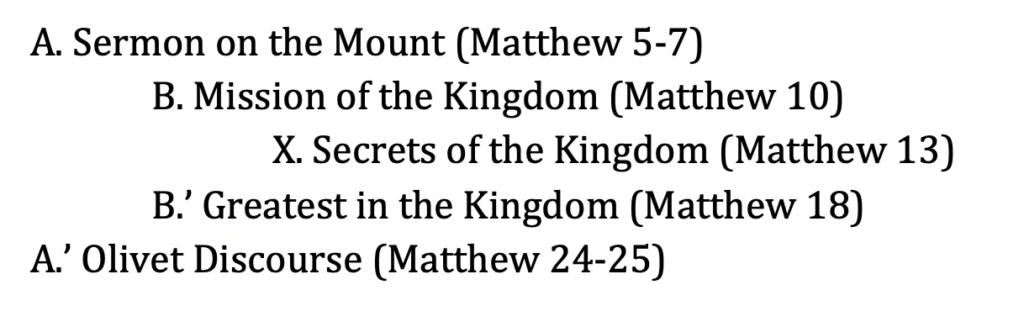

Matthew has placed Chapter 13 as the chiastically central chapter in the book. As many have noted, Matthew contains five teaching blocks of Jesus that conclude with the phrase “when Jesus finished saying these things…” (7:28, 11:1, 13:53, 19:1, 26:1). And these five teaching blocks are chiastically arranged. Each section has both thematic and scenic connections.

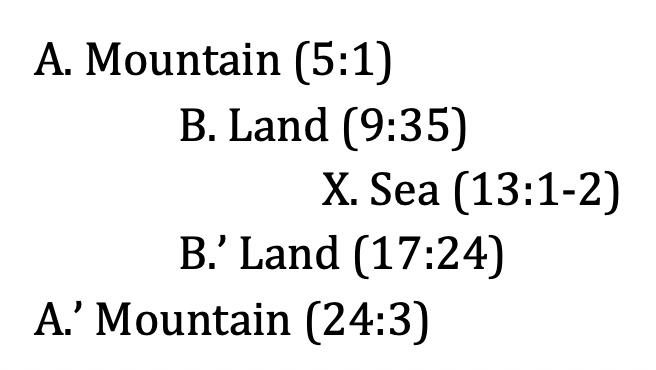

The scenic connections move from mountain to sea and back to a mountain.

Matthew has organized this geographical journey to symbolically communicate Jesus’ greatest action. Jesus descends down into watery death and ascends in glory in the resurrection. Matthew connects the physical objects of water with death (Jesus’ baptism in Matthew 3 and the Gadarene demoniac in Matthew 8) and mountains with glory and exaltation (transfiguration in Matthew 17). Matthew melds form and content into one beautiful design.

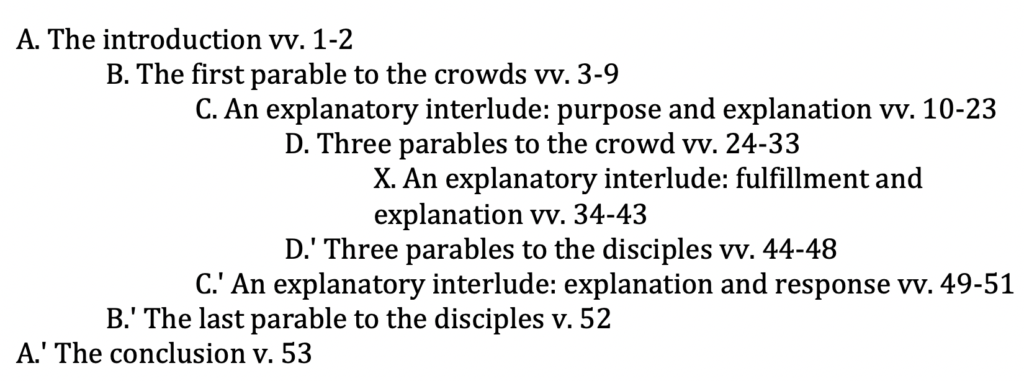

But the secrets go deeper. Not only is Matthew’s Gospel chiastically structured, so also is the central chapter itself, Matthew 13, as David Wenham and Thomas Constable have noted:1

In the central section, vv.34-43, Jesus quotes from Psalm 78. Matthew 13:34-35, “All these things Jesus said to the crowds in parables; indeed, he said nothing to them without a parable. This was to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet: ‘I will open my mouth in parables; I will utter what has been hidden since the foundation of the world.’”

What is striking about this is that Psalm 78 seems to be the center of the Psalter. In 2007, Beat Weber published an article entitled “Psalm 78 als “Mitte” des Psalters? — ein Versuch” (“Psalm 78 as the ‘Middle’ of the Psalter — a Trial/Examination”).2

Weber noted a few lines of evidence that indicated that the final author of the Psalter designed it Psalm 78 as the center of the Psalter. First, the Psalter is organized into 5 books with the central Book 3 containing Psalm 78. Second, within Book 3 you have the majority of the Asaph Psalms, Psalms 73–83, which places Psalm 78 in the center of this sub-collection. And third, Weber explains that the Masoretes noted the centers of books and they marked Psalm 78 as the center of the Psalter.

Psalm 78 in the Narrative Progression of the Psalter

Starting with Gerald Wilson’s dissertation “The Editing of the Hebrew Psalter,” commentators have noticed that the book of Psalms is not a haphazard collection of unrelated songs but was designed with narrative or thematic progression.3

In broadest strokes, the movement of the Psalter progresses from lament to praise. And the Psalter descends to its blackest in Book 3. There, we have Psalm 88, the only lament Psalm without any sort of resolution at the end like a confession of trust or confidence.

Psalm 78

Psalm 78 opens by calling the reader to listen to the Psalm because it is a parable and a dark saying or riddle and that we ought to teach this Psalm because it will recollect God’s “glorious deeds” and “wonders.” The Psalm will go on to review the history of Israel’s disobedience despite God’s great things he had done for them.

Psalm 78:2, the verse that Jesus quotes, reads “I will open my mouth in a parable; I will utter dark sayings from of old.” Even after we read the Psalm, we may justifiably wonder what is “dark” about this Psalm. The word can mean a saying that is enigmatic or like a riddle. What, therefore, is the perplexing strangeness, the particularly parabolic and pedagogical thing we are to learn?

There are at least two enigmatic ideas that are proffered in Psalm 78. First, the enigma of sin. Asaph details the gracious acts of God—the giving of the law, the miracle at the red sea, the guiding glory-cloud, the water from the rock, the rain and manna from heaven—and then concomitantly the dazzlingly opaque sin of Israel in the presence of such wonders. This is dark because explanations are impotent to untangle the purposes that gird the disobedient soul in the face of extraordinary divine favor.

The second enigma is the persistent favor of God. Why does God not only remain but continue his blessings on such a sour people? Two times in the Psalm, God’s perplexing goodness is highlighted – once in the middle and once at the end. In verse 38, after cataloging Israel’s viciousness Asaph says, “Yet he, being compassionate, atoned for their iniquity and did not destroy them; he restrained his anger often and did not stir up all his wrath.” And concluding the Psalm in v. 69-72 Asaph says, “He built his sanctuary like the high heavens, like the earth, which he has founded forever. He chose David his servant and took him from the sheepfolds; from following the nursing ewes he brought him to shepherd Jacob his people, Israel his inheritance. With upright heart he shepherded them and guided them with his skillful hand.”

The particularly perplexing aspect of God’s goodness is his atonement for a serially sinful people and his selection of David to shepherd the undeserving Israel.

Psalm 78 in Matthew 13

After surveying Matthew 13 and Psalm 78, we are now able to piece together Jesus’ and Matthew’s purpose for quoting the Psalm given its multi-layered centrality within both Matthew and the Psalter.

Matthew quotes the second verse of Psalm 78, “I will open my mouth in parables; I will utter what has been hidden since the foundation of the world.” On first reading, you might think that what has been hidden is everything about the kingdom that Jesus discloses in the parables. And while that is certainly true, there must be another layer, and this for two reasons. First, Matthew quotes Psalm 78, implying that what he is doing is connected to that Psalm. Jesus could have just explained his purpose for speaking in parables without quoting Psalm 78. Thus, Psalm 78 will provide an interpretive key to the parables. And second, we have seen that there are multiple layers of centered texts, a phenomenon that requires an explanation.

Jesus quotes Psalm 78:2 for multiple reasons. First, the center of the Psalter and the center of Matthew both contain low points. Book 3 of the Psalter contains the darkest laments and the center of Matthew is both geographically the low point (at and on the sea) as well as the first time where Jesus communicates that he is concealing his teaching to some. By Jesus quoting this psalm he is the quintessential Psalmist – living through and embodying the whole life of Israel from the depths of lament to the heights of praise.

This fits into two other themes in Matthew: Jesus as the new and better Israel and Jesus as a Psalmist. Many commentators have noted the many parallels between Jesus and Israel as Jesus rehearses many of her main actions throughout her history. Regarding Jesus the Psalmist, Matthew introduces this in the genealogy in the first chapter where he changes king Asa’s name to Asaph. Matthew makes this change (along with the change of king Amon to Amos–the prophet) fill out the characterization of the fullness of Jesus as not only king (son of David) and prophet (Amos) but also psalmist – the sweet singer of Israel embodying her lament and praise, death and life. Furthermore, the first designation of Jesus’ lineage in the book of Matthew is as a son of David. And while we commonly associate that relation with kingship, David is just as well known for as the chief Psalmist.

Second, this quotation may also hint at hope as the Psalter moves to praise, perhaps narrative of Matthew will as well.

The Deepest Secret of the Kingdom

But there is one more reason. Matthew 13 is about Jesus’ imparting of the secrets of the kingdom. Perhaps Psalm 78’s double centrality in Matthew provides us with the deepest secret. Israel is in the same place as in Psalm 78 as they are in Matthew 13. God came to Israel in Jesus and he has been doing wonders for nine chapters and Israel has largely rejected him. Yet just like the two graces of Psalm 78, God nevertheless chose a new David to shepherd his people who will atone for their sin. And just like the central depth of lament of Book 3 of the Psalter and the geographic descent from the glorious mountain to the sea in Matthew, the atonement will occur by the Davidic and Asasphic singer going down into death and rising to the mountain of praise.

John Higgins runs the YouTube channel The Bible is Art (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC9sPRleqnVIasw8wnUGBVyA) that produces video essays explaining the literary art of the Bible. You can find more articles at The Bible is Art (https://www.thebibleisart.com) or contact John on twitter @johnbhiggins.

- Literary structure from Dr. Thomas L. Constable at https://www.planobiblechapel.org/tcon/notes/html/nt/matthew/matthew.htm. ↩︎

- Beat Weber, “Psalm 78 als ‘Mitte’ des Psalters? — ein Versuch”, Vol. 88 (2007) 305-325. ↩︎

- Wilson, G.H., The Editing of the Hebrew Psalter (SBL Dissertation Series, 76), Chico: Scholars Press, 1985. ↩︎