For centuries, Christians identified Israel in the Old Testament as a single, literal ethnic group, often called “the Jews.” Even supersessionists – those who believed the Church superseded Israel – assumed the clear-cut, technical definition of “Israel” in the Bible is the ethnic group. However, a deeper dive into Genesis, the very book of beginnings, reveals a radical, theological definition that challenges this assumption: Israel was always intended to be an assembly of different peoples—a church.

The Radical Promise to Abraham

God’s foundational promise to Abraham was that “all the nations of the earth shall be blessed” through his son, a global vision ultimately fulfilled by Jesus Christ. This was a radical idea in a world dominated by national and tribal gods: Moab had its god, Edom had its god. But the Lord revealed himself as the God of all flesh with a plan not just about one ethnicity but about gathering a people from all the world’s peoples. The gospel’s “diversity” wasn’t a later addition; it was the plan from the start.

The true definition of Israel is emphatically repeated at three pivotal moments in the narrative of Jacob, the man renamed Israel. In each instance, the divine name El Shaddai (God Almighty) is invoked, underscoring the vital importance of the promise.

First, at the beginning of the Jacob narrative, Isaac blesses Jacob, saying, “May God Almighty bless you…that you may become a company of peoples“ (k’hal ‘amim; Gen 28:3). The key word, kahal, is the Hebrew equivalent of ekklesia, the Greek word for “church” or “assembly.” Importantly, the plural peoples (‘amim) suggests a gathering of multiple different ethnic groups, not just a single ethnicity becoming numerous. Isaac’s parting blessing is for Jacob to be an assembly of ethnicities.

Second, near the end of the Jacob narrative, God himself appears to Jacob, confirming the name change to Israel and declaring, “I am God Almighty: be fruitful and multiply. A nation and a company of nations (k’hal goyim) shall come from you” (Gen 35:11). This nearly identical blessing frames the entire story of Jacob. By substituting nations (goyim) for peoples (‘amim), God further clarifies that these are not merely physical descendants but a gathering of various political and ethnic entities. The promise is twofold: an ethnic nation (singular, foretelling the literal monarchy) and an assembly of nations (plural). The promise to be a nation is what is new here, confirming that the literal, ethnic nation of Israel with its kings would issue from Jacob, but it is secondary to the promise that Israel is an assembly of nations.

Finally, Jacob restates the promise on his deathbed, reminding his family that God will make him a “company of peoples” (Gen 48:4). This thrice-repetition forces the reader to acknowledge this core definition before Genesis concludes. The literal, singular nation was promised the physical land, but the “company of nations” receives the spiritual reality the land signifies: a place of blessing and safety in covenant with God, what Revelation pictures as the New Jerusalem.

This definition is immediately borne out in Israel’s subsequent history. At the exodus, the nation leaving Egypt included a “mixed multitude” (‘ê-reḇ raḇ), referring to a great mixture of nationalities, foreigners and other slaves who allied with Israel as Pharaoh freed them. The ethnically mixed group fleeing Egypt under the name “Israel” was then called a “holy nation” (goy) and a “special treasure above all peoples” (‘amim) in Exodus 19:5–6, demonstrating that Israel was already what the promises said it would be: a gathering of believers into one holy nation.

Throughout the Old Testament, faith-based inclusion was a constant theme. Moses himself married both a Midianite and a Cushite. Rahab, a Canaanite, became an Israelite by faith and an ancestor of King David and Jesus. Ruth, a Moabite, likewise joined Israel by faith, becoming another ancestor of Christ. Throughout Chronicles, the true Israel is defined as those who worship in God’s temple and submit to the Davidic King. Its opening nine chapters of genealogies define who is in Israel, omitting the northern tribes who did not worship in the temple or submit to the Davidic king. “Israel” can be used of Judah (2 Chron. 20:34, 33:18). Even near the end of the Old Testament chronology, “many from the peoples of the country declared themselves Jews” because they believed in the true God (Est 8:17). By believing in the Lord, ethnic Gentiles became part of “Israel.” The identity of Israel, from beginning to end, was never exclusively one race.

The prophets solidified this theological identity with the concept of the “remnant,” drawing a distinction between physical Israel and the true Israel—an Israel defined by individual choice for God’s calling, not birth. God announced his condemnation of the Northern Kingdom through Hosea, calling them “Not My People” (Lo-ammi) because of their unfaithfulness, which demonstrated that ethnic heritage alone was insufficient for being part of Israel. Yet, in the same context, he spoke of those who will be God’s people, foreshadowing a redeemed, international Israel.

The Church: Israel Continued

The New Testament confirms Israel’s “company of peoples” identity. The apostles Paul and Peter seize on Old Testament prophecies about Israel, especially Hosea 1–2, and apply them to the church, which is the ethnically-mixed body of believers in Christ.

Paul says God has called people “not from among the Jews only, but also from among Gentiles,” quoting Hosea to say, “Those who were not my people I will call my people” (Rom 9:24; cf. Hos 2:23) Similarly, Peter echoes the language of Exodus by calling the ethnically diverse church a “holy nation” and then applies the Hosea promise: “Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people” (1 Pet 2:10; cf. Ex 19:5–6). The inclusion of believing Gentiles into God’s people (“Israel”) was prophesied. James declared that Amos 9:11-12, the re-establishing of “David’s fallen tent,” was being fulfilled by the inclusion of Gentiles into the church (i.e. Israel).

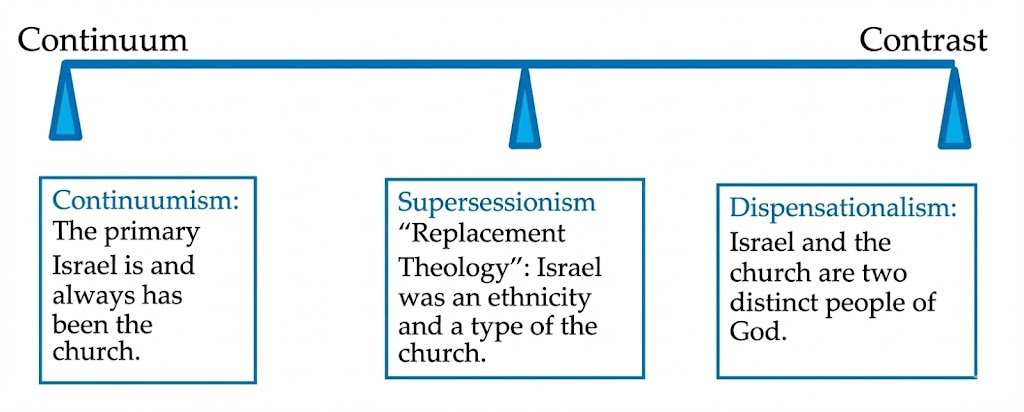

If the Old Testament had been written in English, Jacob might have been told three times that he would become a “church of ethnicities.” The church did not replace Israel because Israel was always and already the church, the promised “assembly of peoples.” The fundamental assumption that Israel was primarily an ethnic people led to slight theological error of supersessionism and the more serious, pernicious error of dispensationalism.

The ”Israel of God” (Gal 6:16) continues to be the gathering of believers from all kinds of peoples and nations. Believers in Christ are the “children of Abraham” (3:7), and the church rightfully carries Israel’s titles of “chosen people” and “holy nation” (1 Pet 2:9). The true Israel is the one olive tree into which both believing Gentiles and believing ethnic Israelites are grafted.

The overwhelming concern of Scripture, from Genesis onward, is for the Israel assembled from all nations: the church.

This is a supplemented and condensed version of “Genesis’ Definition of Israel and the Presupposition Error of Supersessionism” (Trinity Journal, 42NS, 2021) and John Carpenter’s first lecture at the Strauss-Kedamo lectures presented at the Evangelical Theological College (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, October 15, 2025), available online here. John B. Carpenter, Ph.D., is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church, in Danville, VA. and the author of Seven Pillars of a Biblical Church (Wipf and Stock, 2022) and the Covenant Caswell substack.