What do Reformational Catholicism and craft beer have in common? The question seems to beg for a punchline. Better yet, it would be pretty good clickbait for an article on Katharina von Bora’s “spirited” contribution that helped spark the Protestant Reformation.

Well, this is no joke and I am certainly not qualified to trace the impact of the Luther family brewery on 16th century Europe. I do intend to show that the recent microbrewery trend provides us with a useful picture as we imagine the church in the 21st century. Peter Leithart likely did not envision that this association would stem from his recent book, but I find it to be illustrative and helpful.

I believe The End of Protestantism is poised to be a seminal work. At worst, it serves as a provocative appeal that will show itself relevant to challenges in the church over the coming years. Challenges call for cooperative efforts. This book represents an entreaty for greater unity among God’s people.

At its essence, the book is really an exhortation. It calls for obedience and working directionally toward a future unity.

Jesus prayed that His disciples would be united as He is united with his Father (John 17:21). Jesus is in the Father, and the Father in Jesus. Each finds a home in the other. Each dwells in the other in love.

Jesus prayed that the church would exhibit this kind of unity: Each disciple should hospitably receive every other disciple, as the Father receives the Son. Each church should dwell in every other church, as the Son dwells in the Father.((Peter Leithart, The End of Protestantism (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2016), 1.))

“The Father loves the Son and will give Him what he asks. He does not give a stone when Jesus asks for bread. When Jesus asks that His disciples be one, the Father will not give Him bits and fragments. The Father will give the Son a unified church, and the Son will unify the church by his Spirit. That is what the church will be.”((Ibid, 7.))

The message is an appeal to Protestants. “This is an interim ecclesiology and an interim agenda aimed specifically at theologically conservative evangelical Protestant churches.”((Ibid, 5.)) Leithart later states again, “Here, as throughout this book, I do not pretend to address everyone. I speak only to that part of the church with which I am most familiar – the conservative Protestant wing.”((Ibid, 172.))

Although aimed at Protestants, the book addresses the current fragmentation within the church as a whole. It seeks to imagine a different world – one where schism gives way to alliance. Considering the silos in which we Protestants currently function, the message can come off as utopian, or from a practical standpoint, simply unrealistic. But is it? And if we believe it to be so, then how do we posit inescapable separation while confessing “one holy, catholic and apostolic church”?

Ultimately the book sparked more questions than it had answers. This is generally by design when opening a new conversation. Although ideas were discussed, one of the key questions left open-ended was the following: What does this proposed unitiy of Christ’s church look like? Perhaps more specifically, what does this unity look like institutionally?

At the moment we may not have this answer, but we can acknowledge that major change is afoot. As Leithart points out, “The rise of nondenominational churches is one sign that something is up.”((Ibid, 152.))

Something is up. Institutional silos are coming down. Interestingly, the craft beer movement over recent decades can provide us with a pertinent illustration. Surely such a comparison has severe limitations. Market forces governed by God are not the same as the growth of the Church in history through the power of the Holy Spirit. Serving a market under the umbrella of a shared industry mission is fundamentally different than God’s covenant institution with a shared confession, marking out his people in history. Nonetheless, we may find that some representative aspects are useful as we ponder and navigate the coming changes within the Church.

An Unstoppable Trend

“Time moves forward by periodic deaths and resurrections: worlds take form, decay, and collapse, and new worlds take their place.”((Ibid, 101.))

Following the Gutenberg to Google transition, we find ourselves on the eve of something old and yet something very new in history. Death and rebirth, and Babel to break-up are familiar cycles. Yet each iteration moves us along the journey of historical progress and the remaking of the world.

Modernity saw the apex of centralization. Centralized control followed humanity’s quest for diety. This central planning and administration of every aspect of life and society is proving itself to be a fool’s errand. The postmodern world is giving up on the dream. While still supressing the truth and refusing to acknowledge their Creator, they have relinquished the notion that we are in control. An era of decentralization is well underway.

Examples are endless. In the world of medicine, we are moving from a period where we sought to direct every function of the body to one where we are stepping out of the way and supporting these fuctions. Big agriculture is also a glaring example. We lost 94% of our vegetable seed varieties in the 20th century.((SEED: The Untold Story, 2016.)) This is astonishing. Yet, the trend is now moving the other way. Seed exchanges, the local food and real-food movements as well as a rise in family gardens all point to local control. This is good. Every industry and organization is in some way moving this direction.

Society is restructuring. It is reorganizing. The internet has enabled all of this. Decentralized communication and access to information is unleashing and mobilizing the masses. Individuals and regional organizations are making more of the decisions. They have the best information. They have the local perspective. This is the division of labor writ large.

Beerocracy Challenged

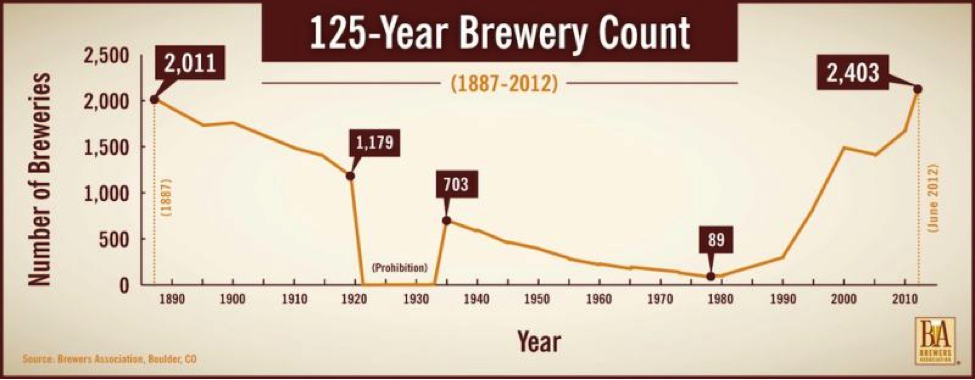

Let’s use the beer industry to further illustrate the point. A popular chart from 2012 says it all.

Since 2012 the number has more than doubled. The number of breweries in the US now stands at over 5000.((https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/2016-craft-beer-year-review-brewers-association/)) To truly witness the extent of decentralization one needs to add the 1.2 million homebrewers into the mix. This is a radical swing over just a few decades.

Prohibition itself is illustrative of the point, but that era aside, the zenith of centralization was reached in 1983. In that year, the top six breweries (Anheuser-Busch, Miller, Heileman, Stroh, Coors and Pabst) controlled 92% of the beer production in the United States.((http://www.beerhistory.com/library/holdings/chronology.shtml)) This high point for “beerocracy” was a low point for consumers. Suffice it to say that beer drinkers in the 1980s were severely deprived. Choice, variety and quality have increased exponentially, with local personality as the backdrop. The passions and creativity of individuals have been unlocked. Again, all of this is very good.

So how can we be sure that this trend is also impacting our church denominations as we know them? Could it be the case that, as Leithart states, “Old denominational maps no longer hold; old denominational barriers are being rearranged.”((Leithart, End of Protestantism, 132.)) If so, why would this be the case?

Well there are likely a host of reasons, but one point from the book is especially relevant. It is the link between our current church divisions and the nation-state – which is itself poised to follow a similar trend line that moves up and to the right.

In The End of Protestantism, Leithart puts forward and supports the thesis that “Denominationalism is the established church of pluralism.”((Ibid, 59. )) This establishment is tied directly to the rise and climax of nationalism throughout the globe over the past two centuries. In our American, pluralistic society, the church’s unified fidelity has been offered to the state. This is the common ground on which she has stood. “…there is an established church in America, one to which American churches have willingly offered their allegiance. It is allegiance to the project of America.”((Ibid, 84-85.)) What we need to understand is that this project, and national projects like it are crumbling all over the world. Although it could be argued that we are witnessing the rise of a new nationalism in an era of Donald Trump and the breakup of the EU, there is no doubt that the centralized, bureaucratic structures of state are being dismantled. Martin Van Creveld has done a yoeman’s work in his book, The Rise and Decline of the State and he articulates the current direction well. “While states continue to carry out some important functions, two centuries after the French Revolution first enslisted modern mass nationalism, many of them seem to have run out of people who believe in them, let alone are willing to act as cannon fodder on their behalf.”((Martin Van Creveld, The Rise and Decline of the State (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 414.))

Nation-states are being dismantled by the same forces that have wrecked Big Beer and big anything else. We are in the death roll of this “project of America”. If Leithart’s connection is on point, the break-up of our established church is underway. Given such, the question is, what do we do? If the current era of division and cetralization “is at best provisional”((Leithart, End of Protestantism, 114.)), and we are to move into another stage of providental history, how should the church seek to conduct herself? How might we pursue unity while still acknowledging differences?

A Worthy Strategy

The craft beer phenomenon provides us with another pertinent example. It addresses another key question. Do all of the trends above equate to increased disunity? Certainly the break-up of centralized structures is an organizational disunity of sorts, but the trend back to more diversity does not require a lack of solidarity.

Since the outset, the modern microbrewery culture has been unified and cooperative. This cooperation has actually fueled the breakup of big beer and enabled the success of local breweries. The culture is unified by a shared purpose and service to local community.

Since the beginning, craft beer has been about community. Before your neighborhood taproom started stocking hoppy IPAs, before most of us sampled nitro-infused coffee porters, before growlers were part of our dinner party lexicon—the craft beer movement was mostly a loose coalition of home brewers tinkering in their basements and sharing recipes over the beginnings of the Internet. And since beer brews in batches, they needed friends to help drink it. In living rooms and back porches across the country, the gospel of good beer was spread one kicked keg at a time.((http://www.yesmagazine.org/new-economy/craft-beer-vs-budweiser-how-small-brewers-are-winning-back-the-neighborhood-20160302))

This cooperation among the community first hit home for me while talking with a brewery owner in my own city. Following an enjoyable conversation just outside his establishment, he stated with some sense of urgency and excitement, “I have to leave to head across town. I’m headed to Swamphead’s anniversary party. They have done some great work the past few years.” He was referring to another brewery in town. Far from being adversarial competitors, or at best competing businesses functioning in silos, here were two breweries celebrating each other’s success. Their leaders know each other. They collaborate. They cooperate. They learn from each other. They sell each other’s beer. This sort of unity is common place within the industry.

One professor of entrepreneurism at California State University San Marcos demonstrates that the extent of cooperation extends back to inception for many breweries.

He points to examples like Plan 9 Ale House in Escondido, California, which received funding from nearby heavy-hitter Stone Brewing Co. “[Stone] should theoretically not be helping a startup; it should be putting up walls,” he says.

But Stone was just returning the favor. Wagner said that years ago Stone sold its first keg to Pizza Port, a “competing” pub brewer that helped Stone with its startup costs. Where some entrepreneurs fixate on how to grab their slice of pie, craft brewers are more concerned with how to grow the pie so everyone gets a hearty slice—or pint. “By working together, they’re building a bigger industry,” he said.

But as we might expect, this level of cooperation is not limited to craft beer. Multiple industries and organizations could be cited. Christian organizations are no exception. In many cases these do in fact go beyond a mutual interest to a shared confession. I interacted with a couple of entrepreneurs recently that were embarking on a bold and ambitious plan for a Christian business alliance. The benefits of membership require only a statement of faith in the Triune God of the Bible. Others like Samaritan Ministries call for a confession of the Christian faith and a sign-off of good standing by a pastor or elder.

Christians always have, to an extent, been involved in cooperation for the gospel. They are beginning to cooperate today at a different level given all of the above trends. The question is, can and should this extend to denominations as a whole? Should unity on a different level be pursued? I would argue that it is happening regardless. The needs of local communities are becoming increasingly met by its members. Central direction is giving way to feet on the ground. Rising challenges of our day call for greater unity. Just because we do not know exactly what that unity would look like institutionally, does not mean we should not actively and intentionally pursue it.

Leithart provides some suggestions as to how church unity might manifest itself. “In such a world, the denominations would acknowledge each other’s discipline, cooperate rather than compete in ministry, strive to resolve theological differences, and come to one mind.”((Leithart, End of Protestantism, 87.)) He notes that getting to this place will not be easy. “Getting from division to federative unity to full communion will be a long, difficult, strife-filled and frustrating process.”((Ibid, 167.))

Conclusion

It is helpful to reemphasize that unity does not equate to complete uniformity. The latter would quash the division of labor. The division of labor was designed by God to further progress in history.

This division of labor is one of the functions denominationalism has served. In some aspects it has supported growth and vibrance. It “has kept American churches from replicating the grand, echoing emptiness of Europe’s cathedrals.”((Ibid, 66.)) …“by virtually every measure it has left the American church far stronger than the monopolistic establishments of Europe. Denominational Christianity has been nothing if not resilient and has carried a living faith into the early twenty-first century. That is no mean achievement.”((Ibid, 69.))

Yet, as noted above, our denominationalism still exists in an age of empire. That is the reason why most efforts at unity were manifested in the twentieth-century as… “a church unified by having a centralized bureaucratic structure.”((Ibid, 33.))

Unlike twentieth century efforts, the trek towards a more unified church will take the path of the current meta-trend of decentralization. “Glocalization” that is fueled by the universal connectivity in an information age will provide opportunity for ideas to turn into action. Microbreweries rooted in a new sense of community are only one particular microcosm and manifestation. As Leithart posits, “For innovative, visionary pastors and civic leaders, though, there are hundreds of realistic, locally based, ecumenically charged opportunities to foster experiments in Christian social and political renewal. Christendom is dead! Long live the micro-Christendoms!” (Emphasis mine) This is my particular passion and one I believe to be shared among many in the church today.

All of this local activity will require a shared confession. A commonly held purpose and mutual commitments are enough for service in the free market. They are not enough to constitute a unified church. God’s people should be ready for increased interaction on theology and practical application. We are woefully unprepared for this at present. An immersion in Scripture at both lay and leadership levels is our only hope.

Speaking of shared confessions, any questions as to what the balance of unity and diversity looks like should be informed by our trinitarian theology. The desire of Christ conveyed in John 17:21 is expressed in the context of a Triune God. For whatever the detailed features of the future picture, the one and the many will be a prominent theme. As the Bible assures us, our one body will always have many parts.

Let’s not ponder too much. Let’s break down the silos and communicate across party lines – not because we want to go soft on our distinctives, but so we can increase the distinctivenss of the church as a whole.((In the book, Leithart demonstrates how in some ways this is already happening all over the world. We will only watch it increase.))

The saints sup at one table covenantally. Is it a worthy exercise to move toward this communion institutionally? If it is possible to mark out the boundaries of our Christian home in history on earth, then what is to keep us from coming out of our separate rooms for a shared meal? Well, likely quite a lot at the moment.

I regard Leithart’s book as a call to at least for now, get us all in the living room for more family discussions.((“The goal should not be to convert other pastors to one’s own tradition. The goal should not be simply to get along in spite of differences. The goal should be to begin to work through differences in a context of communion and prayerful friendship.” (181)) Robust as they might be, we might find that the communication leads to more cooperation for the sake of the gospel. If your particular protestant flavor does not inhibit you, perhaps you can even pop the top on a good craft beer and drink to unity amidst fragmentation.

John Crawford is business leader and future junior fellow at Theopolis.