God is Not There

God is not in the book of Esther. Do a word search and you will get 0 results. Also try Lord, Yahweh, Prayer, Temple, or Sacrifice. Even names with God’s name in them, like Elijah, Jeremiah, or Daniel are missing. The fool says in his heart, “There is no God,” but in Esther, shockingly, there is no God.

Against the backdrop of that terrifying reality, the destruction of God’s people is imminent. The Jews are like sheep without a shepherd, the deck is stacked against them, and all that stands between the Jews and their total destruction in exile is a king, notorious for his parties and their less than Solomonic aftermath.

Yet we find the book of Esther in our Bibles. Not only that, God wrote this book. Historically, both Jews and Christians have agreed on this point. God wrote a book where his name is missing.

For that reason, Esther is a book particularly suited to speak to modernity. The nihilism of Nietzsche and others has gradually seeped into the mainstream culture, so that a once obvious theism has now faded into the shadow of atheism. Our age is what Philip Rieff describes as a “third world” culture, not that it is divested of material goods and wealth, but one that has been stripped of any transcendence and any standard outside of itself. The modern world is one that represents a rupture from the Christian, and even the pagan ages of the past. All you get are atoms in motion. This is all there is.

This cultural atheism has seeped into the modern church as well. David Wells has described the central problem of modern Christians as “the weightlessness of God.” Although we still acknowledge God, we often do so stripping him of his Holiness. “God” is just a term that we use to describe our own inner thoughts. Connecting with God has come to mean little more than connecting with your true self. Theology, once the study of God himself, has become psychology, the study of man’s mind. The transcendence that we acknowledge often functions as little more than our inner personality.

Our culture and our churches are awash in godlessness. So what does the godless book of Esther have to say to us?

So Where is God?

I firmly believe that God is in the book of Ester, not only that, but he spoke it through Mordecai (or another author), making this book in fact God’s speech to us. Because it is God’s Word then, it is designed to tell us about him, to reflect him, and to reveal who he is. This paradox means that even God’s silence speaks. Even God’s hiddenness is a revelation of God.

All this brings up a question then: how can we hear God if he does not speak? How can we see him if he is invisible? How can we feel his presence when he is absent? This is the question that Esther answers for us. Esther is designed to teach us how to hear in the silence and how to see in the darkness. This is the lesson that modern Christians must learn.

How Stories Work

Recently my three year old has taken to telling me a story before I go to bed. He begins, “When I was a little boy” (with a heavy emphasis on the “I”). Although he has heard many stories, he does not quite get how the arc and flow of a story work. He has a commendable start, but after this promising beginning, his stories usually dissolve into a nonsense tale comparable to a piece of abstract art (with giggling as the primary medium).

My son has yet to realize that a story is more than a disconnected string of random names and places. A story has a flow, an arc, a pattern, and a structure. Without that, it is no story. A man sitting in a chair doing nothing is not a story.

In the 20th century authors like Joseph Campbell and C. S. Lewis began to map out the particular patterns that the ancient myths and stories often used. The details of this structure will vary, but a basic structure remains intact. Blockbuster movies know this is also the structure that sells big because it captivates human hearts and minds. Once you have grasped the “monomyth” or “the hero’s journey,” you will find it all around in ancient, medieval, and modern stories.

Through its structure, a story becomes the means that an author uses to communicate to his readers. By its very nature, the story says something in the characters it develops, in the way it resolves, in the problems it deals with.

The Central Hinge of Esther

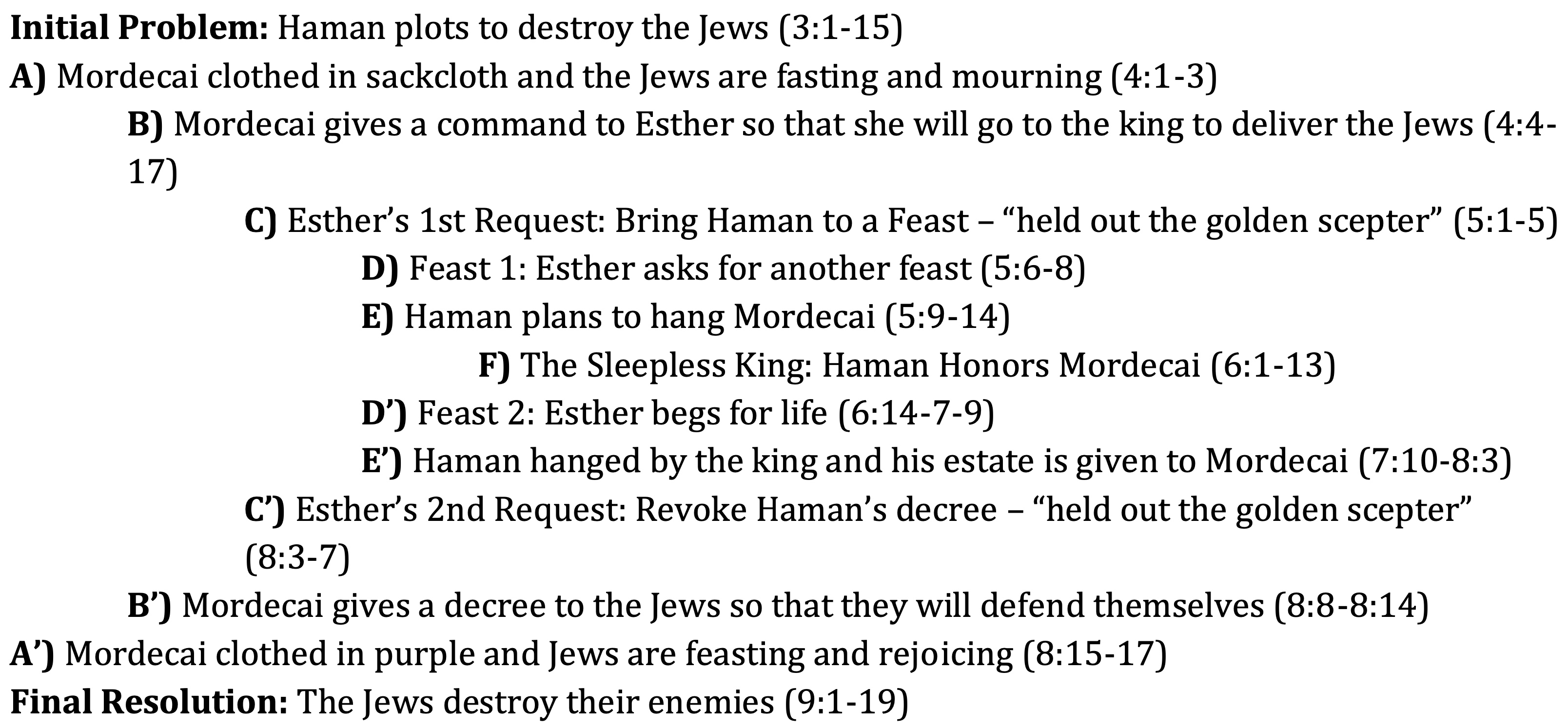

Now this brings us to the story of Esther. There is a basic problem presented on the surface: Haman is going to kill the Jews in exile (Esther 3:6). Haman is an Agagite, related to the ancient people of Amalek. Many years before, Saul (a Benjamite) was supposed to kill Agag (an Amalekite), but he failed in his task, and ultimately ruined his kingship (cf. 1 Samuel 15:20). Now, the conflict between these two tribes continues: Mordecai the Benjamite versus Haman the Amalekite. How will this problem be solved? Like any good story, the resolution does not immediately appear, but is gradually unfolded as the tension builds, suddenly turns, and is finally released reaching to the conclusion. Here is an overview of the main narrative following a chiastic structure:

The initial problem results in a series of events that are even more unfavorable for the Jews. Mordecai mourns in sackcloth. Esther goes to the king, prepared to die, she offers to have a feast with Haman, their archenemy, and then Haman plans to hang Mordecai. The death of the Jews is imminent and Mordecai’s hanging is the first chip to fall into place.

But then, everything begins to change right in the center. Here is the surprising turning point of the story as the built up tension begins to unwind. Haman comes to the king to ask to hang Mordecai, but the reverse happens, and he is called upon to honor Mordecai. So all the plans of the wicked begin to unfold. Haman goes home, and his wife warns him of danger to come. He goes to another feast, but this time, he is accused, and then hanged and his estate is given to Mordecai. Esther gets another decree to save her people, Mordecai delivers the joyful message to the Jews, and the end result is joy and gladness and victory over the Jewish enemies.

This structure is important because it highlights the central passage as the hinge on which the resolution turns. First of all, notice what the hinge is not. The hinge is not Mordecai’s entreaties to Esther, it is not Esther’s brave entrance into the king’s chamber. James Jordan has helpfully noted how Mordecai and Esther are not the model Jewish believers that popular versions often portray them as. The Jews are not saved because we have before us two faithful and righteous heroes.

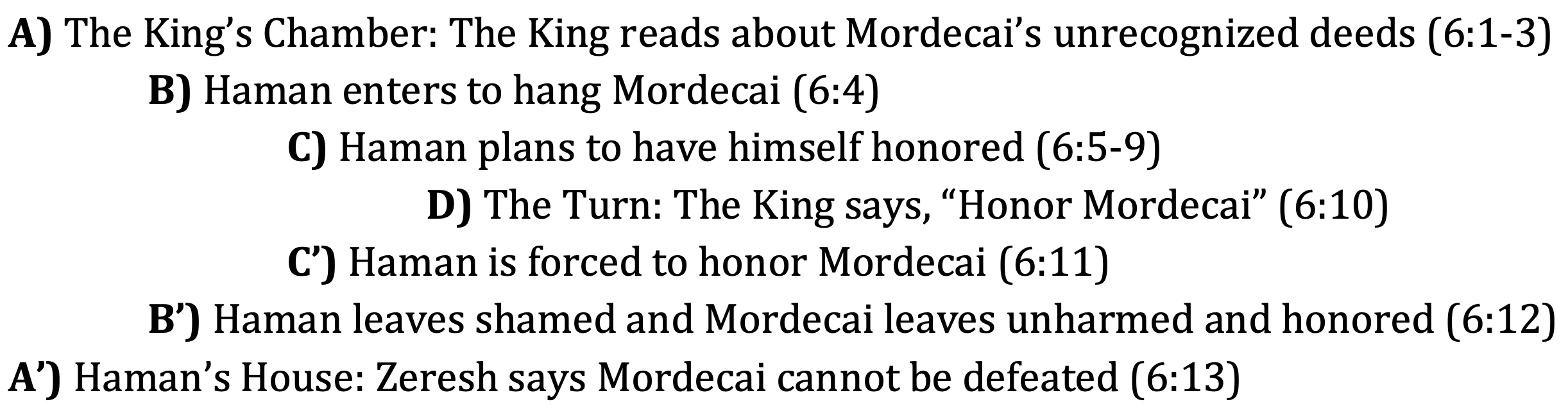

The hinge is almost a let down. It is simply that the king can’t sleep (6:1). To understand this central section, we should zoom in and notice that it is also chiastic:

What is it that brings about the kings command and reversal of Haman’s plans? “On that night the king could not sleep” (6:1). As we trace back the coming destruction of Haman and victory of the Jews it all depends on this little detail: a sleepless king. Hardly an important detail. Yet, the structure of Esther tells us otherwise. Everything depends on this point. If the king had slept, he would not have read the chronicle, and he would not have honored Mordecai, and Haman could have killed him, and Esther would not have had the courage to speak, and the Jews would have been killed. But this is not how the story goes, because the king could not sleep.

God Appears

What does all of this have to do with God? First, we have to zoom out, and then come back to this point. Amalek is a descendent of Esau, and the Amalekites fight with Israel, shortly after the exodus (Exodus 17). In this battle, Moses holds up his staff, and Joshua successfully defeats and routes the enemy. But God is not done with Amalek. He makes a promise to Moses, “I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven” (Exodus 17:14). God’s promise is that he himself will intervene and destroy them.

Now back to Esther. Esther is the story of how God fulfilled his age old promise to destroy Israel’s nascent enemy. But the way God’s hand is revealed in the book of Esther is subtle. God’s mighty hand is not at work here like it is in the ten plagues on Egypt, where Moses continually appears to tell Pharaoh that the plagues are from the hand of the Lord. Instead, we have to read the story, understand the structure, and look closely into the way that it unfolds before us. The simple and unimpressive event of a sleepless night is not meant to show that sometimes random things happen with good outcomes. But rather, in the storied structure of Esther, it is an orchestrated event, a designed event, one designed by God himself for the sake of his people. Here is at play Paul’s principle: God uses the weak things of the world to display his power (2 Corinthians 12:9 and 1 Corinthians 1:25). The sleeplessness of the king in the midst of this story shows that “the king’s heart is a stream of water in the hand of the Lord, he turns it wherever he will.” (Proverbs 21:1).

This is not a new interpretation either. The Septuagint version of Esther makes explicit what is only implicit. While this Greek version of Esther is not the original Hebrew, it does give some insight into how Esther was understood by the Jews of the second century BC. Take a look at chapter 6 verse 1:

“But the Lord removed sleep from the king that night: and he told his servant to bring in the books, the registers of daily events, to read to him.” (Esther 6:1 LXX)

And then look at the end of the chapter that corresponds to this passage:

“If Mordecai is of the race of the Jews, and you have begun to be humbled before him, you will assuredly fall, and you will not be able to withstand him, for the living God is with him. (Est 6:13 LXX)

While God’s name is not in the original Hebrew text, we could say that the LXX version here is more of a commentary than a translation. It verbalizes and makes plain what the overarching structure of the story conveys in a hidden way.

The Theophany of a Hidden God

Theophany means “the visible manifestation of God,” in that sense, Esther shows us a different kind of theophany, a paradoxical theophany. God appears invisibly. And this is a vital lesson for us today. God’s providential work in the world today is more like Esther than like Exodus. And there will come a time when the Lord is fully revealed in his glory, but that is not our present moment. This is why Esther is so important for the modern world. The absence of God’s name in Esther is not trying to tell us that God himself is absent. But rather, it tells us that when God appears to be far way, he is in fact very present. God appears to us, but he appears invisibly, he speaks silently, he reveals himself darkly.

God is writing Esther then to show us that his absence is an invitation to look more closely. We could put it this way. The fact that God seems absent from this world today is not because our eyes have been enlightened and our ears have been opened. God is missing from our vision because we have not opened our eyes wide enough. Like Paul, we must pray for the strength to comprehend the God who is here for his people (cf. Ephesians 3:18). The theologian Herman Bavinck has said that every second of the universe throbs with the heartbeat of eternity. God is present everywhere, yesterday, today, and forever. God is abundantly present and at work in the wasteland of modernity. If you can’t see him, then you need to pick up the story, and start reading.

Ryan Handermann is a pastoral assistant at Trinity Reformed Church and also teaches Latin for Wilson Hill Academy. He lives with his wife and five kids in the north of Idaho where they go foraging for morel mushrooms in the spring, cherry picking in the summer, apple cider pressing in the fall, and try to keep warm in the long, dark winter.