Leviticus 20:22-26

22. And you shall guard all My decrees and all My laws and do them, so that the land will not vomit you out, where I am bringing you thither to live in it. 23. And you shall not walk in the decrees of the nation that I am driving out from before your face, for all of these things they did and I abhorred them. (“Abhor” here is quts, a word that indicates a deep emotional reaction against something, involving rejection and even destruction. See Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament #2002, 1:794.) 24. And I said to you concerning them, You will possess their ground and I shall give it to you to inherit it, a land flowing of milk and honey. I am the Lord your God, who has set you apart from the nations. 25. And so you distinguish between the clean cattle and the unclean, and between the unclean winged thing and the clean; and you shall not render detestable your souls by the cattle or by the winged thing or by anything that crawls on the ground, which I set apart from you as unclean. 26. And you are to be My holy ones, for holy am I, the Lord, and I set you apart from the nations to be Mine.

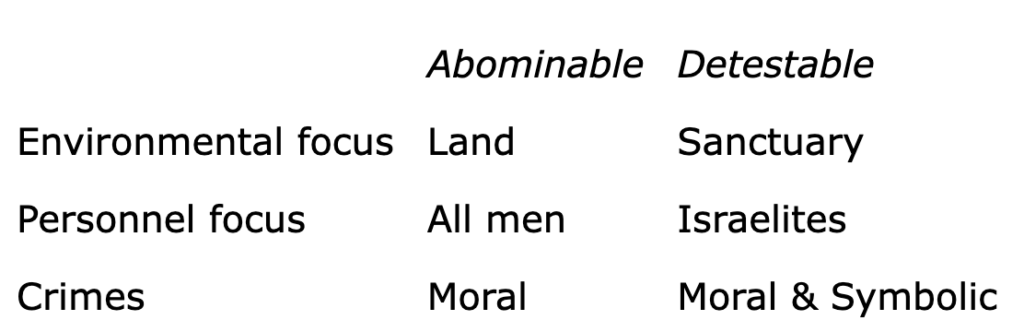

Here it is stated that separating between clean and unclean animals, and regarding the flesh of unclean animals as causing them to become detestable, is a symbol of Israel’s covenantal separation from the nations. The land will vomit them out if they commit general moral abominations. General moral abominations are symbolized by specific detestable acts, primarily having to do with eating the flesh of unclean animals. That which is detestable is a concentrated symbol of that which is abominable.

Leviticus 18:24-30 spoke both of the Israelite and the sojourner. Both could commit abominable acts. Both could become abominable. Both would be spat out of the land if they did so. In contrast Leviticus 20:22-26 speaks only to the Israelite. The Israelite alone is in God’s inner circle. He alone has sanctuary access, so he alone can commit detestable acts. The dietary laws did not apply to the sojourners in the land (Dt. 14:21). The sojourners were not set apart from the nations to be priests to God, but the Israelites were. Thus, when the Canaanites and later on the sojourners committed acts of idolatry, these were abominable, but when Israelites committed these same acts, they were both abominable and detestable.

Leviticus 18 and 20 also differ in that Leviticus 18 speaks of the land’s vomiting out the Canaanites and Israelites, while Leviticus 20 speaks of the Lord’s driving out Israel. In chapter 20 the Israelites are threatened with expulsion for failure to guard, failure to carry out the God-mandated penalties set forth in this passage. The non-priestly Canaanites (Lev. 18) were not judged for failure to guard, but “only” for the abominations themselves. This relates to the difference in position of Israel and the Gentiles, and to the fact that only Israel could commit “detestable” acts. (It also pushes in the direction of seeing the prohibitions of Leviticus 18 as applicable to all men, but the sanctions of Leviticus 20 as applicable only to Israel. If such is the case, then it would primarily be in the Church that Leviticus 20 would apply today. Let me express my thanks to Peter Leithart for this observation, as well as for the observations in this entire paragraph.)

Diagram 1

As we draw this part of our discussion to a close, think back to Adam and Cain.1 The sin of Cain was an intensification of the sin of Adam. Adam was cast from the sanctuary-garden of Eden, while Cain was cast from the land of Eden. Adam’s sin was a detestable act, eating forbidden food. Cain’s sin was an abominable act, murdering his brother. Before the creation of a new garden-sanctuary (the Tabernacle and its precincts), detestable acts were not possible. Abominable acts, in the land, were possible, however. Thus, for their abominable acts in the land, the Canaanites were driven from it (Lev. 18:27). Also, because the Egyptians viewed shepherding as an abominable occupation, the Israelites were not permitted to dwell in their land but were given the separate land of Goshen (Gen. 46:34). Thus, the land-sanctuary distinction, and the attendant abominable-detestable distinction, is woven into the warp and woof of the entire Old Adamic Covenant from creation to the cross.

(The fall of the Sethites, which resulted in the Flood and the destruction of the entire world, cannot be repeated. God guaranteed that he would prevent man’s sin from ever reaching that point of extremity again (Gen. 8:21; 11:1-9). Thus, Leviticus gives no “third” category of sin that results in the destruction of the world. It is only sanctuary and land that are in view.)

In the New Covenant, however, the sanctuary is in heaven. There are no more earthly garden-sanctuaries. As a result, the New Testament writings focus almost exclusively on moral sins, abominations. The only opportunity to commit a detestable act occurs when the church is united liturgically with the heavenly Christ by the Spirit during Lord’s Day worship. Geographical considerations no longer apply, only liturgical ones, and the only rite specified is the Lord’s Supper. Abuse of the Lord’s Supper is the one detestable act applicable in the New Covenant, just as eating the one forbidden fruit was the only detestable act in the first Garden. Just as the detestable act of eating forbidden fruit brought death to Adam, and all the detestable acts of the Mosaic covenant brought “ceremonial death” (uncleanness) to the Israelites, so the detestable act of abusing the Lord’s Supper brings death in the New Covenant (1 Cor. 11:30). The proper application of the dietary laws of Leviticus is to the sacrament.

The Holy, the Abominable, and the Detestable

Leviticus 11:44 and 45 state that the reason for the dietary laws was that Israel was to be holy as God is holy. Holiness has to do with transcendence. In God’s case, transcendence means His utter separation from His creation. While man is made in God’s image, yet in another sense God is always utterly unlike man, as the Creator is different from the creature. Thus, an affirmation of God’s holiness is always an affirmation of His awesome transcendence, including His ethical separation from sin.

In man’s case, holiness means integrity. Each man or woman is to have integrity in himself or herself. Each is unique. We know, paradoxical as it may sound, that it is as we come to be more and more dependent on God, that simultaneously we come to have more and more uniqueness and integrity in ourselves.2 The more we cleave to God, the more transcendent we become over our circumstances.

This idea of integrity, then, is the link between the holiness of God and that of man. God’s holiness and integrity was expressed in the Old Covenant by the boundaries of the Tabernacle and Temple. These preserved God’s transcendence, both metaphysical and ethical. The human body is analogous to the Tabernacle and Temple. Thus, the holiness of the individual person is related to what he takes into his body.

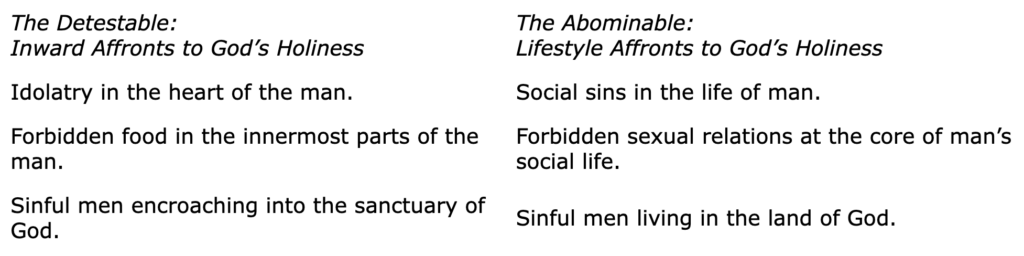

Holiness is the opposite of both the abominable and of the detestable. In terms of what God does in His land, God never acts abominably. In terms of what God is in His Person, God never receives anything detestable. Similarly, the holy man is not to act abominably in his life, in the land, or else he will be cast out of the land. Just so, the holy man is not to permit detestable things into his inner person, into the holy sanctuary of his heart and body, lest he be cast out of God’s sanctuary.

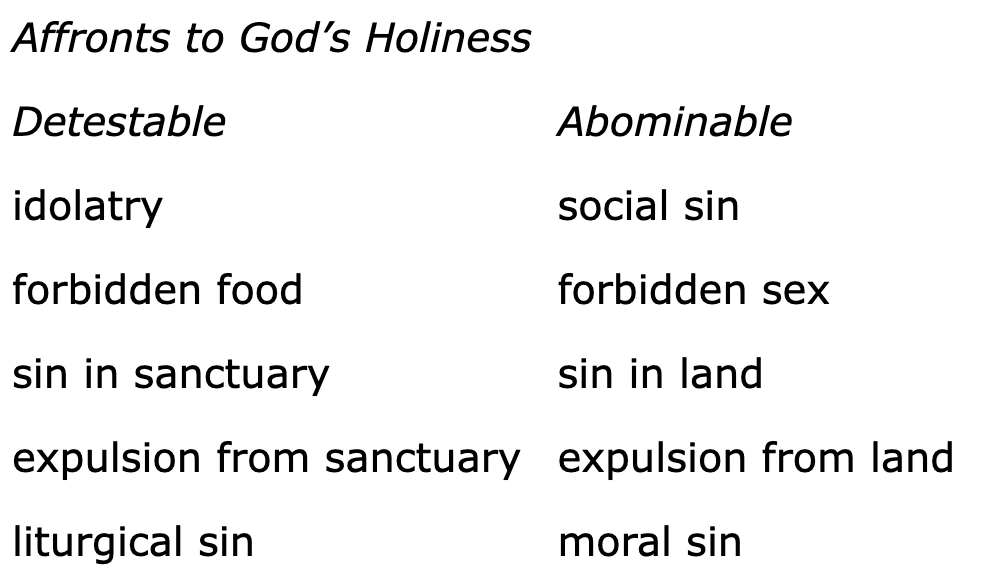

Thus, we have the following analogies:

Diagram 2

Diagram 3

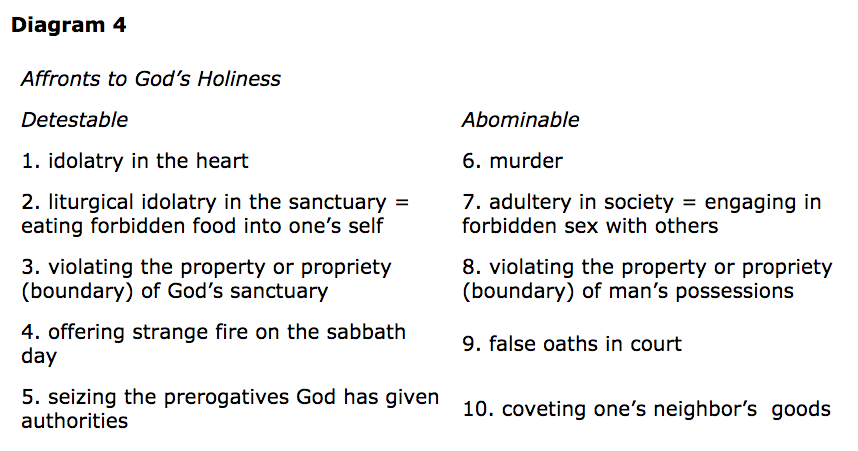

In the section preceding this one, we saw that detestable idolatry can be profitably correlated with the Second Commandment, while abominable behavior can be correlated with the First. It is possible and profitable to do this another way as well. The first five commandments bear analogies with the last five. The First Commandment supports God’s absolute holiness and integrity, while the Sixth supports the holiness and integrity of man: manslaughter is forbidden. Just so, the Second Commandment supports God’s relational holiness, while the Seventh supports the relational holiness of man: adultery is forbidden. With this in mind, we can see that detestable acts focus on the first five commandments, sins against God’s holiness, while abominable acts focus on the second five commandments, sins against the integrity and holiness of other human beings.

God’s Name (Third Commandment) was enthroned in His sanctuary, and thus violations of the sanctuary “stole” from His glory. Just so, the Eighth Commandment forbids stealing from our fellow men, and would be an abomination.

Similarly, the sabbath was the day when oaths to God were taken (Fourth Commandment), and violation of it would be detestable. The Ninth Commandment focuses on false testimony given under oath in human courts, which would be abominations.

Finally, honoring those in authority (Fifth Commandment) means not seizing their robes, which means not eating of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil–a detestable act. Not coveting the goods of someone who is one’s equal (Tenth Commandment) would be an abomination.

(On the Ten Commandments, their arrangement and meaning, see James B. Jordan, Covenant Sequence in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, available from Biblical Horizons .)

Thus we can improve our list as follows:

In summary, that which is detestable has to do with man’s inward being, his heart and flesh, while that which is abominable has to do with man’s life. Similarly, that which is detestable has to do with direct affronts to God’s presence, before His sanctuary, while that which abominable has to do with indirect affronts to God’s presence, in His land and in connection with His images. The detestable is an aggravated form of the abominable, because it goes to the inward parts of the man, and because it more directly confronts the holiness of God in His sanctuary.

One final point remains to be noted. Since God’s personal holiness is manifested in His House, so also man’s personal holiness is to be manifested not only in his person but also in his house. Accordingly, the second half of Leviticus 11 concerns defilements not of the person but of the home. Just as Decay can come upon both a man and his house, so also the defilements caused by unclean animal carcasses can come upon both a man and his house. Keeping the one clean is symbolically equivalent to keeping the other clean.

Conclusion

The “abomination of desolation” in Daniel is literally the “detestable thing of desolation.” The reference is clearly to idolatry and not to moral sin. This point has generally been recognized by interpreters, who point to Antiochus Epiphanes’ sacrificing a pig on God’s altar and to Titus’s setting up idolatrous imperial standards around Jerusalem. What the interpreters have not realized is that neither Epiphanes nor Titus were capable of violating God’s Temple, because neither had any true and legal access to it. The only people who could violate the Temple were the priests, for they alone had proper access to it. Thus, the “detestable act causing desolation” can only have been committed by Israelites, focussed in the persons of their representatives, the priests, and focussed most closely on the person of the High Priest.

If Daniel’s prophecy had spoken of an “abomination of desolation,” it would be possible to see the actions of Antiochus and of Titus as fulfilling the prophecies. As it is, however, the clear difference in usage between “abomination” and “detestable” eliminates any moral and political interpretation of the prophecy, and focuses our attention upon the liturgical and religious.

James Jordan was scholar-in-residence of Theopolis. This post originally appeared at Biblical Horizons.

Notes: