The primary task of many Biblical scholars (as they see it) is to explain how and why the Biblical text acquired its final form—i.e., what source material it used, how that material was expanded/redacted, who expanded/redacted it, why they did so, what the weather was like at the time, etc.

A few days ago on The-Platform-Formerly-Known-as-Twitter, I made a comment about a particular explanation of how certain parts of the exodus narrative acquired their final form, and certain folk seem to have found it helpful, so I thought I’d try to put it in blog form. (Yes, sometimes some people find some things written on Twitter to be of some help.)

Introduction

Sceptically-driven explanations of how Biblical texts acquired their form generally consist of three steps.

Step One: Highlight various features of the text that don’t read as we might expect them to.

Step Two: Stress how awkward these features of the text are, preferably with words like ‘weird’ and ‘bizarre’. Be careful to stress what the text (‘weirdly’) fails to mention, and assume that your expectations require no recalibration.

Step Three: Proffer a hypothesis that explains how these features of the text arose, ideally in terms of a power play and/or of authors editing texts for self-serving reasons.

Consider the following example.

The Moses-Only Explanation of the Exodus

When we first meet Moses, he doesn’t have an older brother. A son of Levi marries a daughter of Levi, and has a son with her (Moses). Moses is watched over by his sister, but is not said to have any brothers.

Throughout Moses’s early life in Egypt and Midian, there’s still no mention of Moses’ brothers.

A bit later, however, God promises to provide Moses with someone to help him in his task, at which point his brother Aaron suddenly enters the narrative. Weird, right? Even more weird is the fact that Aaron was able to wander out into the desert to meet Moses. (Weren’t the Hebrews meant to be enslaved?) Something’s clearly up.

Then, as the narrative continues, God gives Moses power to turn water into blood, but when the time comes to perform the relevant sign, Moses tells Aaron to perform it instead, which also happens in the case of two other signs. Why?

The answer—or so the explanation goes—is that an Aaronite clan among Israel’s priestly ranks wanted to cement their place in the priesthood, so they added their ancestor (Aaron) into the Exodus narrative. They thus created various oddities in the text which allow us to identify what they did (but which for some reason they either didn’t notice or didn’t fix). The Aaronites were of course perfectly placed to make such additions to the Biblical text (since it was housed and maintained in the Temple). And so, with a few brief strokes of the pen, they made themselves Moses’ brothers’ descendants and permanently cemented their place in Israel’s priesthood.

The Problem

What are we supposed to make of the Moses-Only Explanation? Well, one thing we could do is consider whether its alleged ‘oddities’ are really that odd. Given that Moses grows up in Pharaoh’s house and then flees to Midian on his own, is it really much of a surprise his early years in Egypt and Midian don’t mention Aaron? And does the fact that Pharaoh didn’t let the entire Hebrew nation go out into the desert to worship their God for three days really mean it would have been impossible for Aaron to visit Midian?

Another issue we might want to consider is whether our expectations about how a 3,000-year-old text from a foreign culture would/should have been written (given certain conditions) count for much.

But the most significant problem with hypotheses such as the Moses-Only Explanation is the fact that they can prove pretty much anything we want them to.

For instance, suppose we want to craft an Aaron-Only Explanation of the exodus narrative. No problem. We simply highlight a different set of ‘oddities’ in the text and proffer ‘the Aaron-Only Hypothesis’ as their solution.

After all, Moses’s appearance in the exodus narrative is pretty hard to believe, isn’t it? Why would Pharaoh’s daughter adopt a child whom her father wanted killed? And how would she have kept his identity secret? And isn’t it a bit of a coincidence that the exodus narrative involves exactly the same number of plagues as the number of words/commandments given to Moses on Mount Sinai?

Clearly, then, the exodus story was originally just about Aaron and the three signs he performed, but a rival clan of Mosesites wanted to muscle their way into Israel’s priesthood, so they added their ancestor (Moses) into the exodus story (and bumped the number of plagues up to ten), and claimed that Moses was the guy who really led Israel out of Egypt, not Aaron. (After all, no-one would have added Aaron the older brother into Moses’s story since it would raise questions about Moses’s legitimacy to lead Israel.)

The Mosesites also credited their ancestor with a miraculous birth story, which they based on the events of the exodus (hence both stories revolve around salvation through water—a dead giveaway), and then in order to explain why Moses wasn’t mentioned in the official records of the time, they had him grow up in secrecy in Egypt.

That’s why we have various references to ‘the sons of Aaron’ in the Psalms and in the Chroniclers’ land allocation and yet not a single mention of the sons of Moses (weird, huh?). And that’s why God doesn’t summon Moses’s sons to appear before him on Mount Sinai (Exod. 24), but Aaron’s (I mean, come on!).

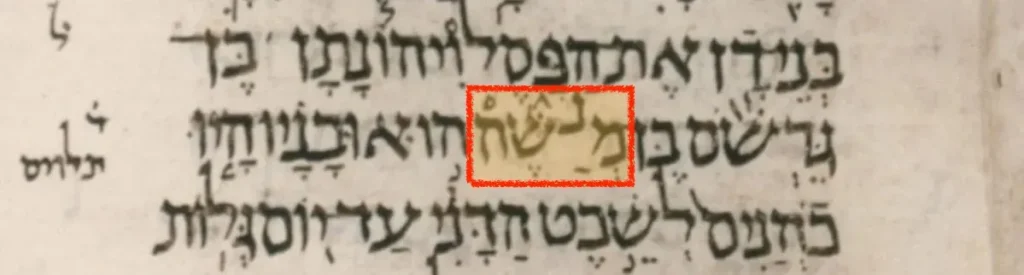

Two priestly factions thus arose in Israel’s history—the Aaronites and the Mosesites—and they continually strove against one another. As a result, we have Moses criticised for his Cushite wife in Numbers 12, which the pro-Moses faction countered with the story about the cloud and God vindicating their man. And look—some crafty Aaronites even inserted the letter nun in Judges 18 as part of an unsuccessful attempt to remove the name of Moses from priestly history!

Etc., Etc., Etc.

Conclusion

So what can we conclude from all this? The main point, I think, is nicely summarised in the old adage ‘That which proves too much proves nothing’. Hypotheses that can’t be falsified don’t ultimately count for much. And many text-critical hypotheses fall into precisely that category. Of course, I ultimately disbelieve the majority of sceptical text-critical hypotheses not because of their lack of falsifiability, but because of my belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. But it’s nice to know that such hypotheses have defeaters aside from a belief in inerrancy.

James Bejon attends a church in Romford, London, where he fellowships, is taught, and teaches. He presently works at Tyndale House in Cambridge (https://academic.tyndalehouse.com), whose aim is to make high-quality biblical scholarship available as widely as possible. This article was first published at his Substack, Thoughts on Scripture.