1. Goal

This paper’s goal is to identify and describe a literary strategy employed by scripture, namely using two episodes that cover similar territory or themes using details drawn from opposite ends of a number of spectrums. Once described the reader may recognize numerous other instances of this strategy in scripture. A consequence is that some episodes viewed by source critics as being disparate prove to be coherent. What they have suggested is redaction is shown to be highly indicative of sophisticated design. The creation and garden episodes are an example. They are not awkwardly placed stories from different traditions, rather, they are dependent halves of a single literary composition. This insight should shape one’s interpretive lens.

2. Beginnings

Scripture’s opening chapter describes God using His word to separate and call forth a hospitable land from a chaotic sea. In the next chapter the ground and water, and their properties of sterility and fecundity invert, rather than land emerging from a lifeless sea, a river of living water gushes from a sterile and featureless plain without plant or bush.

The Creation (G1:1-2:3) and Garden (G2:4-5:32) stories differ, each starts at opposite ends of a land-water spectrum. One begins with a formless and void, the other without bush or plant. Yet they are similar. Each describes a beginning. Both stages are initially featureless and undesirable. Land or water emerges from its opposite, reversing the undesirable state.

This paper sees these differences as elegant complements, not awkward contradictions. While tensions exist between the accounts, those tensions are not oversight, they are deliberate. The two accounts are stocked with inversions, polarities and reversals.

These two episodes are not two independent stories, but dependent halves of a whole. Their themes, details, and images form a template. This template is instantiated numerous times in Genesis and throughout scripture. Creation stories are told to describe a separation or an exodus. Garden stories describe events leading to unions and births. The storyline of Genesis is driven forward by repeated pairs of stories that draw upon Genesis’ first two stories of beginnings.

3. Stage

In Creation humanity is tasked with ruling and subduing the world. God is portrayed as transcendent, the scale is universal. Humanity is charged to rule and subdue creatures of sky, land, and sea(G1:26). In the Garden, the scale is local. God is approachable. Humanity is tasked with serving and guarding the garden G2:15).

Consider how each account describes humanity’s composition. At Creation humanity appears in response to God’s expressed will, neither built nor formed. They are in the image and likeness of the transcendent God. In Garden man’s origin is not lofty, he is formed from the ground. His ‘name’ could be translated as dirty. He doesn’t abide in a heavenly court. Beasts, not angels, are evaluated as potential companions. The woman is then separated from the man after the animals are deemed unsuitable.

The land animals are created before the humans in Creation, but in Garden the order is reversed. There is room to interpret the text to say that the animals had already been formed (G2:19). But, the plainest reading of the text shows them formed after the man, and in the same way (formed from the ground). The scene opens with the narrative note that there is no shrub or plant because the man had not been formed (G2:5). Independent of the sequence, food would not be available for the animals until the human was formed.

4. Topics

God commands humanity to be fruitful and multiply in Creation. A command regarding childbearing is absent from Garden. Man and Woman know each other after taking the forbidden fruit. Only then do they become aware of their nakedness. Offspring is subsequent and seemingly consequent to their disobedience.1

Creation begins with God working for six days, then resting on the seventh. In Garden God rests (G2:15 נוח) humanity in the garden. After humanity sins, they are cursed to toil.

In both scenes God’s word plays a central role. In Creation God’s word is irresistible, the elements arrange themselves as the Creator’s word expresses his will. In Garden the snake throws shade on God’s word, humanity disobeys.

Consider how the image of humanity is handled in both texts. While Creation ends with humanity bearing the image of God, the Garden ends with humanity resembling the snake. The slippery snake used its word to destabilize and deceive. Note how humanity uses its word after taking the fruit: when God calls the man to account, he blames the woman. The man who earlier sang praise for the gift of the woman, now throws it back on God for putting her there! Likewise, the woman blames the snake.

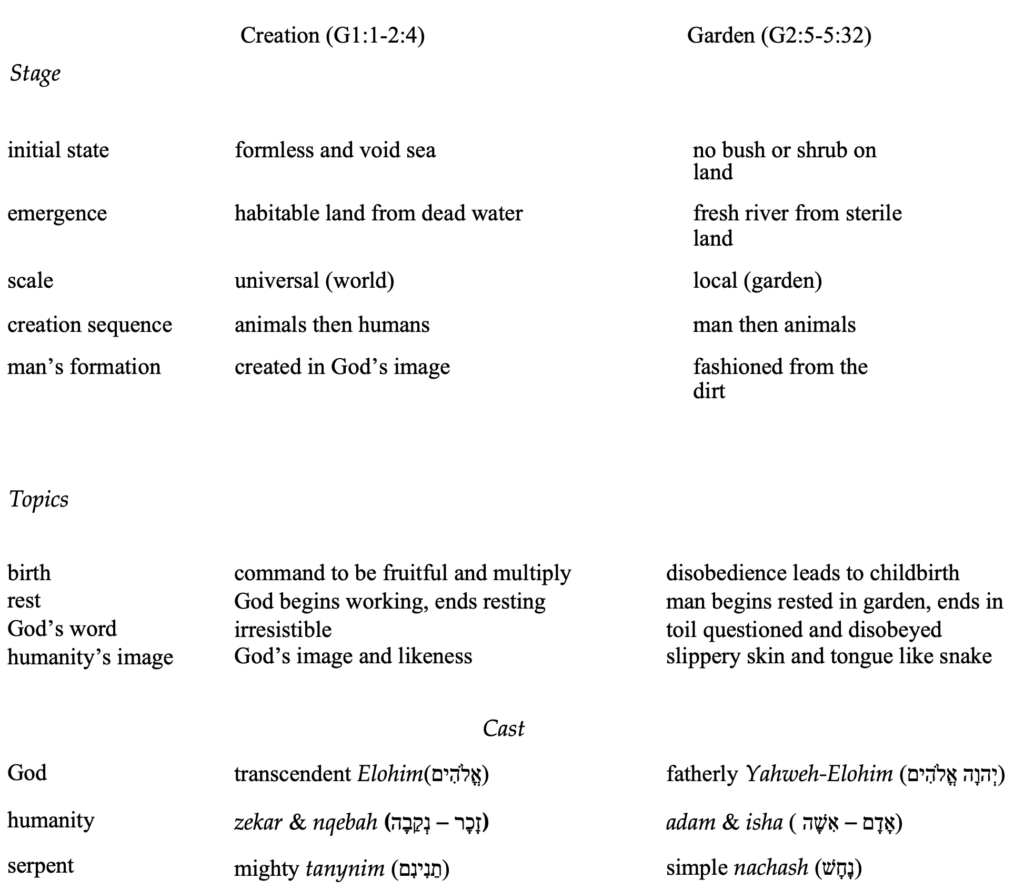

Table 1: Polarities in Beginning Episodes

Before the fall, the man and woman existed together naked and without shame. After they eat from the forbidden fruit, they notice they are naked. The term for naked (ערם) is also used to describe the snake when it is introduced (G3:1). It is often translated as ‘crafty’ (ESV). The introduction of shameless naked humanity and the crafty snake is separated by only seven words. The difference between the two instances of this same word is that the first is plural.

The shared characteristic between naked humanity and the crafty snake is the quality of slippery. Humanity and the snake have smooth and hairless (relatively) skin in distinction from the land animals2. After taking the fruit, this word’s other meaning is also shared. The serpent’s and humanity’s words are slippery and subtly deceptive, each has a forked tongue. Humanity employs their words for evasion, rather than to fulfill their charge to guard and serve. They were to marshal creation with their words, like God, subduing and ruling the slippery invading snake. They allowed their hungers for both food and significance (to be like God!) be guided by the serpent’s words rather than God’s. This led to their sudden observation that they too had become slippery (ערם –arum). Their state of undress had not changed, but now they were crafty. They employed words not like God, but to frustrate and dissemble. They sought to hide this persuasion, but it was immediately exposed under God’s interrogation. God’s questions revealed avoidance and blame-shifting. The serpent would be cursed to live on the ground, humanity was cursed to die in the ground.

5. Cast

Both stories share the same cast of God, humans, and a snake.

The word used for the snake in the garden is nachash (נָחָשׁ). This same word is used to describe what appears when Moses throws his staff down (Ex4:3). The snake from Moses’ staff is later described in the text using another word for snake, taniyn (Ex7:9 תַנִין)

A taniyn also appears in the Creation narrative. It heads the list of creatures in the sea on day five (G1:21). It is described using this noun’s plural form. The term is modified by an adjective meaning great or big. Other living creatures from days five and six are grouped by classes, for example the swarming, the winged, the creepers, or the behemma, which alludes to the large land animals. Great snakes belongs in a much finer taxonomical record than catalogued in Creation. This is a singular creature that is referred to with a ‘plural of majesty’. The narrator already employs the ‘plural of majesty’ for God (אֳלֹהִים). The snake’s description is emphasized with the adjective of great. The word ‘dragon’ describes a great snake.3

If this understanding is correct, then day 5 conforms to a pattern already exhibited on days 4 and 6. Days 4 and 6 each populate their respective habitats with special or particular creatures to rule over generic classes of creatures. Day 4 includes big and small lights to rule the day and night, these are particular lights followed by the generic stars. Day 6 describes man and woman, who rule land and sea, these are particular. They rule the creepers and the land animals, these are general. Day 5, like days 4 and 6, includes a single definite creature that has ruling capacity, the tanynim (תַנִינִם) . Then the other creatures are listed using very general classes, the winged and the swarmers.

This understanding of the term tanynim provides us with another contrast. Creation has a mythological feel. It is cast with a powerful God in the sky, a dragon in the sea, and ideal humanity who rules the land. The sharp boundaries established by God’s word are subdued by humanity. While in the Garden God is approachable, the snake is a snidely villain, the woman is impressionable and naive, the man is simple and spineless.

6. Plot

The relationship between these stories is similar to that of Platonic and Aristotelian thought, or deductive vs inductive reasoning. But these stories are not alternatives. They are not different frameworks or schools of thought. They are also not clumsily cobbled traditions munged together by unsophisticated nomads. Each story is a necessary half of a whole, but a whole what?

The prepositional phrase opening scripture lacks a definite article. It should read ‘In beginning God…’ , not ‘In the beginning God…’ How does this small difference change the meaning? It asks the reader to understand the events that follow as a process, rather than as an event. The process involves God using his word to separate his creation from chaos, darkness, and bondage, then delivering it to light, and freedom, a habitat where life can endure and thrive. This episode leads to a habitable land, but the same process is used to bring Abram out from Ur or to deliver Israel from Egypt.

Simply separating from darkness or chaos is incomplete. Life is cyclic. In addition to a separation, there must be a joining of two kinds of seed, resulting in new life. garden is a joining story.

A complete creative act is a process of separating and joining. We are birthed through water, we then mature, we grow increasingly independent. When ready, we make a new home and join with another, and the process begins again. Genesis is a book about the persistence of life expressed in units of generations.

This paper looks at the first separate-join pair in detail. Both creation and garden describe beginnings but from complementary vantages. One describes land drawn from water, the other water emerging from land. creation is cast with mighty characters on a universal stage, garden uses humble actors on a small stage.

It is misleading to characterize the inversions and reversals between these two stories as contradictions. We recognize that Jewish narrative values symmetry in its literary structures. These two texts exhibit another form of symmetry. A man leaves, flees, or wanders from home; separation. Then through a deception or manipulation join, forming a new home, they birth children, bringing into existence a new generation. Genesis pairs the instances of separation and joining with complements, polarities and inversions of similar scenes and relationships. Consider further instances of this device:

- Wandering Sarai is taken into an Egyptian king’s harem, while Abram remains passive. We turn the page and the wandering Egyptian Hagar is taken into Abram’s bosom through Sarai’s manipulations. One encounter leads to an escape, the other leads to a birth.

- Jacob is his mother’s favorite brother in Canaan, while Jacob has a favorite sister wife in Haran. Jacob deceives his blind father to receive a material blessing in Canaan, Jacob’s father-in-law deceives him while he is blind in the dark tent as Jacob works to materially bless him in Haran. One encounter leads to Jacob fleeing, the other leads to births.

- Judah, Leah’s son, is identified by the articles he left at his conjugal visit with his veiled, but honorable, daughter-in-law. Joseph, Rachel’s son, is identified by the article he left while fleeing the advances of the dishonorable wife of his lord. Both scenes describe a union or attempted union of a man and woman from the same household. The unions involve men and women in asymmetric positions, Judah is in the position of power, Joseph is vulnerable. One encounter leads to births for Jacob, the other leads to jail for Joseph but eventually leads to escape from famine for Jacob’s whole family.

These are similar stories, with the same themes, but each is told from opposite ends of numerous spectrums. Each pair has the kind of symmetry exhibited first by CREATION and GARDEN. One half describes a separation, the other a joining that leads to birth.

The literary character described in this paper is not limited to short episodes in Genesis. It is also found between books. Esther and Ruth is an example4. Esther is a young Israelite woman in a gentile empire delivered from Haman’s machinations, Ruth is gentile woman in a Judean village who gives birth to David’s ancestor. Esther is primarily a CREATION story, Ruth recalls themes in the GARDEN story.

Christian canon itself is two parts. The Old Testament describes a separation of God’s son (Ex4:22), Israel, from the world. The New Testament describes a joining of the world to Israel’s God through his son Jesus. The Old Testament is primarily a CREATION story, the New Testament is primarily a GARDEN story.

Conclusion

A joy of biblical studies is the recognition of scripture’s artistry and sophistication. The design identified in this paper pervades scripture at multiple scales. It contributes coherence to the full canon and guides its readers to search the mind that produced it. Scripture rewards one who leaves simple ways and walks in the way of insight (Prov 9 :6). This paper offers insights into the discrepancies found in the Bible’s opening chapters that simple conclusions which are based on assumptions of multiple sources lack. My hope is that these insights will encourage others to walk in scripture’s light.

Scott Fairbanks is a student of scripture. He lives in Corvallis, OR with his wife and three children. He has begun maintaining a website to contain his observations on scripture at Lotech Wonders.

- The subsequent scene shows humanity involved in agriculture and animal husbandry… and murder. They control the course of life and death, both plant and animal. These vocations are consequence of knowing good and evil. ↩︎

- David Roseberg preserves the connection behind these like words in his published translation A Literary Bible. Roseberg describes the serpent as ‘smooth-tongued’ and has the adam replying to God that he hid because he was ‘smooth-skinned’. ↩︎

- John’s vision in Revelation also sees a great serpent arising from the sea to challenge God with its words (R12:9,17, 13:5). ↩︎

- Their many similarities and polarities are outlined here:

https://theopolisinstitute.com/esther-and-ruth-grain-and-fruit/ ↩︎