I started looking at a sequence of psalms on divine Kingship (Psalms 93-100) in my last post, part of a series looking at the Old Testament’s witness to Yahweh’s exercise of absolute mastery over his cosmos. I am not trying to “prove” a doctrine of creation ex nihilo directly from Book 4 of the Psalter—but I do think that ex nihilo is a “good and necessary consequence” of the fact of divine monarchia (sole rule or sovereignty) that is set forward in such texts as Psalms 90-106.

In this post, I carry my investigation forward by looking at Psalms 96 and 98. The last post noted the grounding of cosmic stability in the steadfastness of the divine throne (Psalm 93)—and noted further the interweaving of “cosmic” and “ethnic” concerns as the world’s Creator is identified as the Shepherd of a particular people (Psalm 95). This post points to a continuing emphasis in Psalms 96 and 98 on the world’s createdness—which the nations are now summoned to acknowledge.

Israel’s task is to summon the world to recognize what she already knows: that Yahweh is the Creator-King—and is greatly to be praised.

Psalms of Yahweh’s Kingship (part 2 of 3): Psalms 96 and 98

Psalms 96-99 belong together because they share a common general structure of calls to worship God or to rejoice before him, and they give justifications for these actions. I will look at the interconnections among all four psalms in my next post; here I focus only on the complementary Psalms 96 and 98.

Psalms 96 and 98 are both imperative psalms that begin with the command to “sing to Yahweh a new song”; both give prominence to Yahweh’s “salvation” and his “wonders” (listed in that order in Psalm 96, but in reverse order in Psalm 98); and both end in a series of jussives that bid the physical world to rejoice because Yahweh comes (or has come) to judge the world and its peoples with faithfulness and equity.

Structurally, Psalm 96 is divided into two larger stanzas (vv. 1-6 and 7-13), each further sub-divided into two strophes, the strophic divisions falling between vv. 1-3, 4-6, 7-10, and 11-13. The structural balance effected by the sequence of imperatives in vv. 1-3 and 7-10 is noteworthy: while vv. 1-3 contain verbs (predominantly) of speaking (“sing” [vv. 1-2], “bless” [v. 2], “proclaim” [v. 2], “tell” [v. 3]) and vv. 7-10 contain verbs (predominantly) of cultic worship (“ascribe” [vv. 7-8], “bring” an offering [v. 8], “enter” his courts [v. 8], “worship” [v. 9], “tremble” [v. 9], “say” [v. 10]), the threefold “ascribe” in vv. 7-8 reflect the threefold “sing” in vv. 1-2; also, “declare among the nations” in v. 3 corresponds to “say among the nations” in v. 10. The string of imperatives turn into jussives in vv. 11-12 (“let them be glad” [v. 11], “let it rejoice” [v. 11], “let it thunder” [v. 11], “let it exult” [v. 12], “let them shout for joy” [v. 12]) as praise “ripples” outward from the nations into the physical order.

The addressees of the imperatives in Psalm 96 are ambiguous: Although “all the earth” is commanded to sing in v. 1, the nations are then spoken about in the third person in v. 3 (“declare among the nations”). The commands to offer cultic worship in vv. 7-9, however, are clearly addressed to the “clans of the peoples,” and it seems that no change of addressee is envisioned after the “all the earth” of v. 1 (and v. 9): the nations are both those who spread the report about Yahweh among the nations, and those who come to worship. The content of the message is designated in pairs as Yahweh’s “name” and his “salvation,” his “glory” and his “wonders” in vv. 2 and 3, respectively.

The question then arises whether the “wonders” and (especially) the “salvation” refer to historical events or to something else. While the parallel in Ps. 98—which we will examine shortly—suggests a historical referent, the internal flow of thought in Ps. 96 suggests that historical acts are not quite what is in view here. Verses 4-6 explain (introduced by “for” in vv. 4 and 5) that God is to be praised for his greatness, his acts as creator and his royal qualities. According to the chiastically arranged vv. 4-5 (arranged as: Yahweh – all gods – all gods – Yahweh), Yahweh’s exaltation is specified as his identity as Creator—implying that other gods are mere idols: “For Yahweh is great and much acclaimed; he is to be revered above all gods. For all the gods of the peoples are idols, but Yahweh made the heavens (vv. 4-5).

Given this cosmic or “heavenly” context, the “sanctuary” referenced in v. 6—the place where Yahweh’s kingly “glory,” “majesty,” “strength,” and “splendor” are present—might refer to the heavens just mentioned; however, a reference to Yahweh’s earthly sanctuary fits the context better, since that is where the liturgical actions in the ensuing verses would presumably take place. The worship of Yahweh in vv. 7-10 culminates in the declaration: “Say among the nations, ‘The Lord is king! Surely the world is firmly established; it shall never be moved. He will judge the peoples with equity.’”

I would tentatively enclose the second and third clauses of v. 10 within quotation marks, as items which the nations themselves now acclaim. As commentators routinely note, Psalm 96 is here deeply resonant with Psalm 93, surveyed in my previous post. Most importantly, Ps. 96:10 “quotes” 93:1 as the nations now acknowledge the created stability of the world—under the kingship of Yahweh—of which Israel has already been a witness, and are told to proclaim Yahweh’s intent to judge the peoples equitably.[1]

Further, the “sanctuary” where the nations have come both to behold and to ascribe “strength” to Yahweh (vv. 6-7), is understood to be the same as the “house” for which holiness is fitting in Ps. 93:5, where Yahweh was clothed and girded with “strength” (93:1, as similarly in 96:6-7).

The final movement of Psalm 96 (vv. 11-13) is a summons to the physical order—the chief features of which (implies the context) Yahweh made, and made stable—to praise Yahweh:

11 Let the heavens be glad, and let the earth rejoice;

let the sea roar, and all that fills it;

12 let the field exult, and everything in it.

Then let all the trees of the forest sing for joy

13 before the Lord; for he is coming,

for he is coming to judge the earth.

He will judge the world with righteousness,

and the peoples with his faithfulness.

We will return to the roaring of the sea when we examine the parallel passage in Psalm 98.

The structural and thematic parallels between Pss. 96 and 98 can be seen if it is remembered that Ps. 96 opened with (A) a call to sing/speak (vv. 1-3) followed by (B) reasons expressed in two kî-clauses (vv. 4-6), followed by (C) more imperatives (vv. 7-10) and (D) a call to cosmic praise expressed in jussives (vv. 11-13). Similarly, Ps. 98 opens with (A) an imperative to sing (v. 1a) followed by (B) the reasons for singing expressed by one (lengthy) kî-clause (vv. 1b-3), followed by (C) more imperatives (vv. 4-6) and (D) a call to cosmic praise expressed in jussives (vv. 7-9).

The chief structural differences are that section (A) of Ps. 98 is very brief, while section (B) is lengthy and relies on only one Hebrew kî; but the psalms are note-worthily similar in that both contain a declaration of Yahweh’s kingship at the end of section (C). More interestingly, section (B) of Ps. 96 emphasized Yahweh’s work in creation—his supremacy over the gods was constituted by his creation of the heavens—whereas Ps. 98’s section (B) is full of covenant language and focuses on “deliverance.” “Our God” has remembered his hesed and his “faithfulness” for the “house of Israel,” and he has manifested his “vindication” (vv. 2-3): of particular (three-fold) importance, he has wrought “victory” or “salvation” (stated twice as a noun, and once as a verb).

Unlike Ps. 96, the context of Ps. 98 (“Our God” in v. 3) makes clear that Israel is the speaker of the Psalm: but Ps. 98 emphasizes that Yahweh’s deliverance happens in front of the on-looking nations (v. 2); and, just as in Ps. 96, the nations (“all the earth,” v. 4) are again addressed and told to shout and sing to Yahweh, and the cosmos also is once again told to join in the praise:

7 Let the sea roar, and all that fills it;

the world and those who live in it.

8 Let the floods clap their hands;

let the hills sing together for joy

9 at the presence of the Lord, for he is coming

to judge the earth.

He will judge the world with righteousness,

and the peoples with equity.

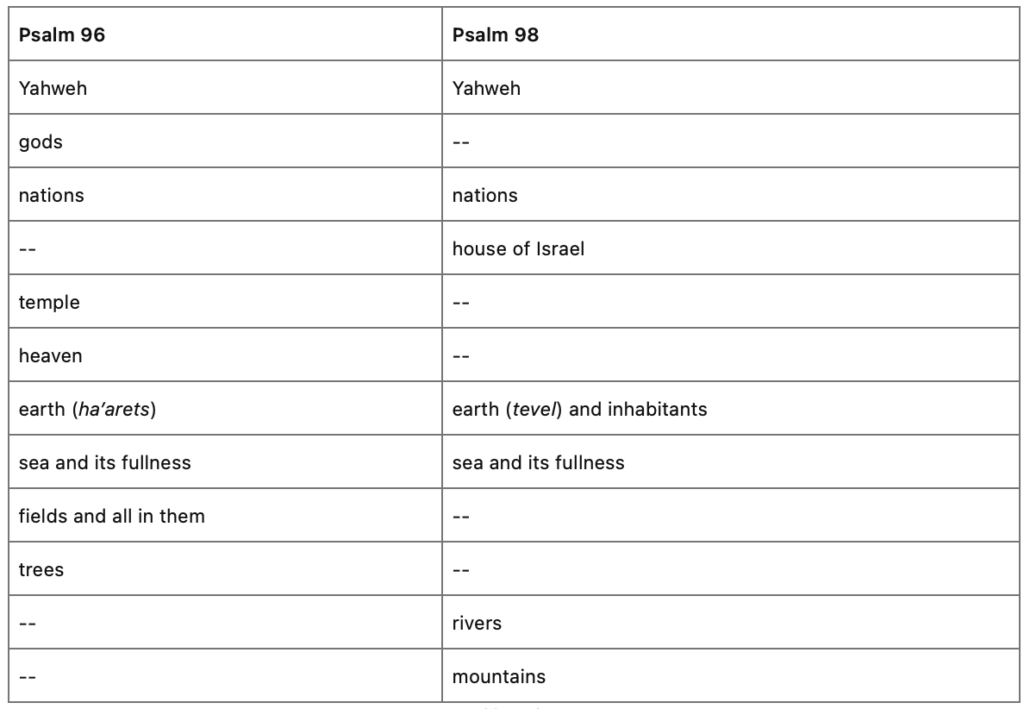

For the sake of comparison, it may be helpful to summarize the actants in Psalms 96 and 98:[2]

We may note that the lists suggest a certain complementarity: Taken together, Psalms 96 and 98 present a picture of all the major features of the physical world—along with their inhabitants—praising Yahweh. The praise of Yahweh is fitting, since his “wonders” are manifest both in the making of the world and in his faithful dealings (specifically, his “salvation”) with Israel. We may note, in passing, that the references to the “roaring” of the sea do not seem to refer to any notion of primal Chaoskampf. The sea simply vocalizes its impulse to praise and to celebrate in a manner that befits its nature, adding an impressive and thunderous note to the chorus of praise.

Israel’s witness—and so also the Church’s—must include elements of cosmology and history: Yahweh is supreme over both. He made the world, and brought Israel out of Egypt. He made the world, and raised Jesus from the dead. The createdness of the world-order is itself an item of revelation, and (just so) not something that we can afford to gloss over: In summoning the nations to worship the One who elected Israel and raised Jesus, we summon them to the worship of their very own Creator.

Stephen Long is a PhD candidate in Christianity and Judaism in Antiquity at the University of Notre Dame.

[1] Among many interesting ways in which Psalms 96 and 98 complement one another, here in Ps. 96 Yahweh will judge the peoples with equity (v. 10) but also with faithfulness (v. 13), and in Ps. 98 one is to remember Yahweh’s faithfulness to Israel (v. 3) and exult in his equitable judgment of the peoples (v. 9).

[2] Cf. Leene, Newness in Old Testament Prophecy (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 22.