In the first part of this series, we showed that God declared that the division between man and woman would be “not good.” There was a division between heaven and earth, which, in contrast to the rest of the creation account, is conspicuously not described as “good,” and there would be a division between man and woman, which was “not good.” God then gives Adam, in his priestly and princely capacity, the responsibility to guard the garden.

Of all the things in the garden, the one thing Adam was to protect above all others was his wife, and his first and most essential act of guardianship was to teach her thoroughly and accurately to remember the true command. His second act of guarding her was to protect the garden from any violation, and especially to protect the most valuable thing in the garden, which is she herself.

In contrast to the traditional and near-universal understanding of Genesis, Adam’s first failure was not his disobedience to the command not to eat of the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Rather, his first failure was his disobedience to the command to guard the garden. At the very least, he failed to keep out an animal transgressor, a sneaking field beast. He failed even to try.

What animal am I referring to? To the nāḥāš.

The nāḥāš (serpent) is first seen as a shrewd (ʿārûm) transgressor. He is the primal trickster on whom the trickster gods of paganism are based. His deceptive nature is contrasted with the innocence of the man and woman via a pun. The word for “naked” as in “naked and not ashamed” is a close homonym for “wise” as in “the wisest beast of the field.” The man and his wife were ʿārûm but not ashamed, and the serpent was ʿārûm out of all the beasts of the field, with no interruption in the original text.

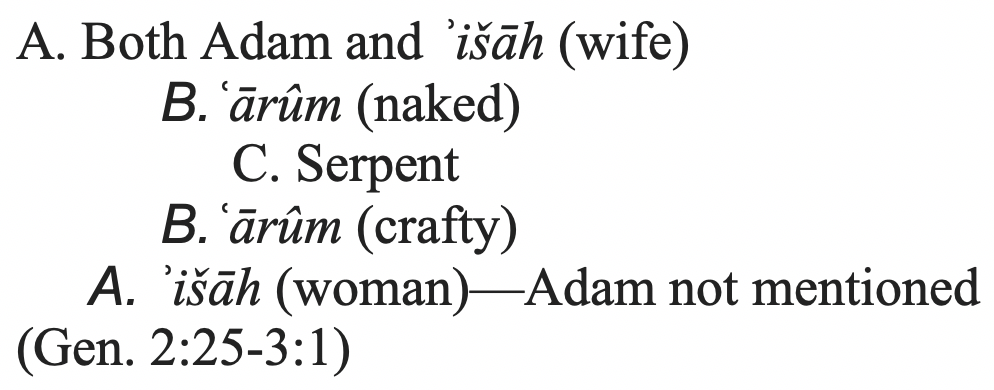

The careful reader will notice not only the parallel between the twin words for “innocent” and “crafty,” but also the parallel use of the word ʾišāh, woman or wife.

Looking more closely at those key words we find a structure like this:

When we see the structure, we see the counter-positions; and when we see the counterpoise, we can notice the contrasts. This passage is clearly a literary unit, which is obscured by the chapter divisions. There is a contrast between the two types of ʿārûm, one innocent and the other crafty. But there is also a contrast between the two mentions of ʾišāh, one mentioned along with a husband and the other not. This sense of the aloneness of ʾišāh should overshadow the entire temptation account which follows. Adam is conspicuously not mentioned.

Keeping the context intact would have us see that the serpent was talking to the “wife.” This brings out an element to the story which is powerfully explanatory, especially if we continue to translate ʾišāh as wife during the entire temptation—dare I say, seduction—account. Over and over again, we’re forced to ask the question, “Where is Adam?” while his wife is being deceived. This is, at least in part, what she was created for: to help Adam guard the garden from interlopers precisely like this one. He was created to protect her from interlopers precisely like this one. They were to be a team, the woman helping the man in his guardian work. She was also at the same time the direct beneficiary of his charge in that she was a part of the garden which he had been ordered to guard.

Adam failed to guard her from the serpent, and she failed to be a helper who faces him and repeats back to him the commands of God. Instead, he stands by passively while his wife is infected by deceit, and after that she in turn infects him by turning back towards her husband and handing him the spiritually poisoned fruit. They then turn away from each other, hiding their most private parts from one another behind loincloths of leaves.

Then when the King appears, they scatter. They lack solidarity, the attribute of being invested in one another’s good. Instead, they calculate their interests separately. Finally, he turns fully against her interest, blaming her before their mutual Judge for his own treason. He offers her up as a scapegoat, a human sacrifice to God in order to save himself. And Adam takes the blaming of his wife to the next logical conclusion, that is the scapegoating of God Himself. If it’s not Adam’s fault but rather his wife’s, then who gave Adam his wife? Adam’s treason is to invert the order of the kingdom: The Prince hides behind the damsel; the Prince judges the King.

The woman’s rebellion is less complete. She, in fact, tells the truth about her disobedience. According to St. Paul, the serpent really did deceive her:

For Adam was first formed, then Eve.

And Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression.

Notwithstanding she shall be saved in childbearing, if they continue in faith and charity and holiness with sobriety (1 Tim. 2:13-3:1 KJV)

Interestingly, virtually the same word which St. Paul uses to describe the deception of the woman in the New Testament is used in the Septuagint translation of Adam’s defense before Yahweh. The principle difference is that St. Paul’s word choice intensifies the word through the addition of a prefix, that is he intensifies the deception itself. To St. Paul, the serpent is at least as deceptive to Eve as she claimed originally, and probably more so. If anything, she played down the degree to which the serpent deceived her, at least in contrast to St. Paul’s later evaluation. Of course, Paul had thousands of years of additional knowledge about just how deceitful the serpent’s ways could be:

καὶ εἶπεν κύριος ὁ θεὸς τῇ γυναικί τί τοῦτο ἐποίησας καὶ εἶπεν ἡ γυνή ὁ ὄφις ἠπάτησέν με καὶ ἔφαγον (Gen. 3:13 BGT). καὶ Ἀδὰμ οὐκ ἠπατήθη, ἡ δὲ γυνὴ ἐξαπατηθεῖσα ἐν παραβάσει γέγονεν· (1 Tim. 2:14 BGT)

Also, to her credit, the woman acknowledged that she had acted, “and I ate,” though her confession is not complete: she does not fess up to having given the fruit to her husband.

A careful reading of Scripture shows that John MacArthur’s reading of Genesis is deeply flawed. Adam failed in his primary duties and allowed the serpent to deceive his bride, directly in front of him. He didn’t prevent the serpent from entering the garden, and when it did, he didn’t intervene to prevent it from deceiving his bride. Adam’s duty to defend the garden and instruct his bride in the commandments were both ignored.

In the conclusion of this series, we’ll show the consequences of Adam and Eve’s sin, and how, once deceived by the serpent, they turned against each other.

This series is concluded, HERE.

Jerry Bowyer is Editor of Town Hall Finance, serves on the Editorial Board of Salem Communications, is Resident Economist with Kingdom Advisors, and is President of Bowyer Research. He holds a Sacred Theology Licentiate from the Collegium Augustinianum and a Bachelor’s degree from Robert Morris University.