Chiastic structures are found all over the Bible, and in recent decades commentators have become more adept at spotting them. But identifying these literary structures is only part of the challenge. There remains the challenge of understanding what they mean.

Part of the answer is found in the recognition that the meaning of the Bible itself includes the beauty and elegance of its literary form. “Meaning” should not be reduced to abstraction – to propositional statements or doctrinal affirmations. The Bible does have meaning in this sense, of course; but it also has meaning in the same way that Beethoven’s 5th Symphony has meaning, or Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” has meaning, or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” has meaning.

Solzhenitsyn’s novel does not just mean “Stalinism is bad”, or even “Stalinism is really bad, and here are a few hundred pages of reasons why.” What it means is found in the very experience of encountering the text, of seeing the horror of the gulags through Ivan’s glazed eyes and laconic prose, of feeling the cold, of tasting the soup, of knowing that Solzhenitsyn himself had been there. If you don’t feel anything, you don’t understand.

In a similar way, part of the meaning of a chiasm is found in the sheer delight of seeing it, of experiencing it. Learning to “understand” the Bible in this sense is rather like learning to “understand” Beethoven – simply switch off your smartphone for a few evenings, turn the music on, close your eyes, and listen. Once Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic have led you through the first four Symphonies, you’ll begin to grasp the fifth.

At the same time there is something to be said for interpretive theory. Just as someone who understands the development of symphonic form and Beethoven’s place at the transition from late Classical to early Romantic is in a better position to appreciate those first four notes, so also we’ll be in a better position to enjoy the Bible’s literary beauty (and therefore its meaning) if we have some idea of how biblical literary conventions work.

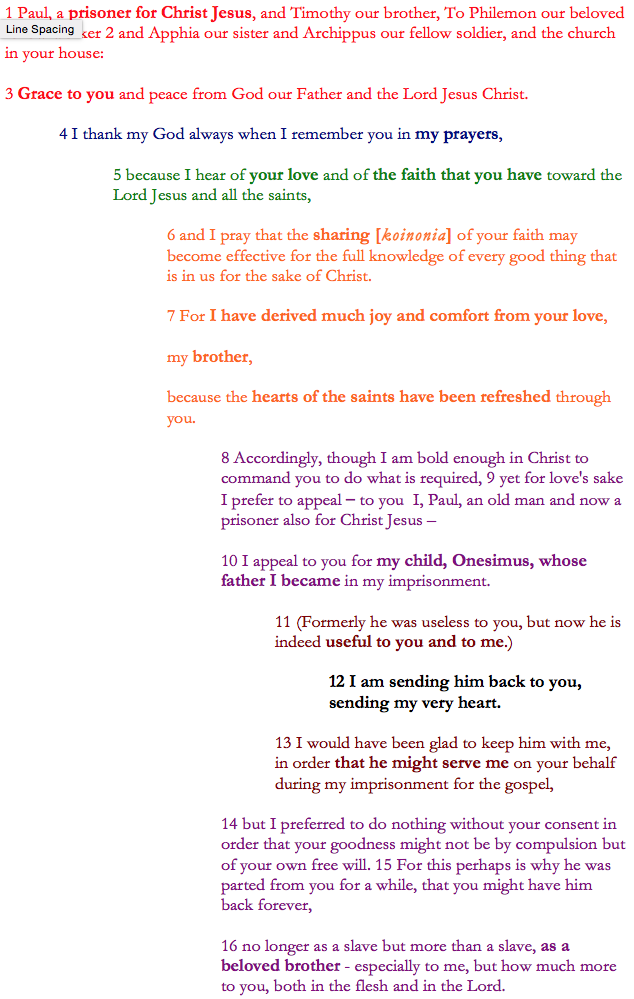

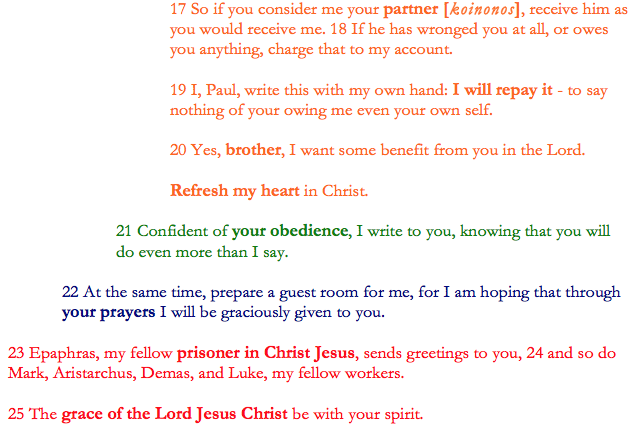

To take one example, consider the book of Philemon. Here’s the structure, with some key words highlighted, and corresponding elements identified by indentation and color

Notice first that the chiastic structure (A-B-C-D // D-C-B-A) is combined with what is sometimes called a panel structure (1-2-3 // 1-2-3), so that within some of the corresponding chiastic elements we also find panel-type correspondences. This is particularly obvious in section D (highlighted in orange), in which at least four panel-type subdivisions are discernible (partner; joy derived, now will be repaid; brother; refresh heart), but it’s also pretty clear in sections A (red) and E (purple).

Now consider some of the corresponding elements in the chiasm, and notice how they mutually interpret each other. For example, in section C (green), Paul anticipates that Philemon’s “love” and “faith” (v. 5) will be shown in his “obedience” (v. 21) in regard to Onesimus. The chiastic structure itself draws attention to the familiar Pauline connection between faith and faithfulness, between trusting in Christ and displaying our trust by our commitment to obey him in everything, even when it is costly.

We can be very sure that for Philemon to take Paul’s letter seriously would have cost him a very great deal, not just in financial terms (does anyone seriously think that Philemon would have taken up Paul’s offer of compensation in v. 19?), but also in the loss of face and increased tension with other slave-owners who would (rightly, as it turns out) have perceived Philemon’s generous treatment of Onisemus as an implicit criticism of their attitude to their own slaves.

In section D (orange), a series of correspondences highlights Philemon’s obligations. Just as Philemon has the privilege of being able to share [koinōnia] his faith, so Paul urges him to act as his partner [koinōnos] in receiving Onesimus as he would receive Paul himself (v. 17). Just as Paul has received much from Philemon (v. 7), so also he is committed to “repay” (v. 17), though of course Philemon owes him much more, so if Philemon wants to talk about repayment, he’d better bring a credit card. Just as the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through Philemon in the past (v. 7), so now Paul wants to receive that same refreshment from him (v. 20).

Again and again Paul visits and revisits the Christian virtue of reciprocity, of giving-back, of doing to others as you would have them do to you. Freely you have received, now freely give – and here’s what it looks like when giving starts to bite.

Again, in section E (purple), just as Paul became a Father and a brother to Onesimus (v. 10), so now Paul urges Philemon to receive him back as a brother (v. 16). Here is Pauline ecclesiology writ large: it is not possible to be a member of Christ’s body without also having many fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters in Christ. And just as with our biological families, we don’t get to choose our siblings. We’re stuck with them, and if Christ has welcomed the runaway slave (which he has, since he’s Paul’s brother, and my brother’s brother is my brother too), then his former master is required to do the same.

Finally, notice the subtle changes of rhetorical stance highlighted by the correspondences in section B (blue). Here Paul revisits the theme of prayer, but with a twist: in v. 4 Paul thanks God for Philemon, who at this stage in the letter would have been feeling fairly comfortable, as it’s nice when people pray for you. By contrast, in v. 22 Philemon’s prayers are in view, and this time if he gets what he’s been praying for then it’s going to be very difficult to sidestep the moral force of Paul’s appeal. Be careful what you pray for, Philemon.

Steve Jeffery is Minister at Emmanuel Evangelical Church in London, England.