Meanings of Remembrance

Both Luke’s account of the upper room (Luke 22:14–23) and Paul’s recounting in 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 record Jesus’ words that the Supper in the distribution of bread: “do this in remembrance of me” (τοῦτο ποιεῖτε εἰς τὴν ἐμὴν ἀνάμνησιν).1 1 Corinthians 11:25 repeats the words in the distribution of the cup as well. The key word is anamnesis (ἀνάμνησις), usually translated “remembrance.” The majority of Reformed interpreters took this as a straightforward instruction to the church to perform the eucharistic rite in such a way and for the purpose that worshipers will be reminded of Jesus’ work of redemption. Expressing this understanding, in The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, Luther enjoins:

During the mass, we should do nothing with greater zeal (indeed, it demands all our zeal) than to set before our eyes, meditate upon, and ponder these words, these promises of Christ—for they truly constitute the mass itself—in order to exercise, nourish, increase, and strengthen our faith in them by this daily remembrance. For this is what he commands, when he says: “Do this in remembrance of me.”2

Note the emphasis Luther has upon the active intellectual engagement of the individual participant. They are to “ponder” the words and promises of Christ. So, also, Calvin says:

When he delivered the institution of the sacrament to the apostles, he taught them to do it in remembrance of him, which Paul interprets, “to show forth his death,” (1 Cor. 11:26.) … that we ourselves may glorify him by our confession, and by our example excite others also to give him glory. Here, again, we see what the aim of the sacrament is, namely, to keep us in remembrance of Christ’s death.3

Calvin indicates that the primary purpose of the eucharist is to bring Christ’s death to the mind of the worshipers. The object of the sacrament is to keep us remembering Christ. By thus showing forth Christ’s death, the Supper is conceived as a public confession to the world.

Many modern interpreters also take the anamnesis in this way. R.C. Sproul writes:

In a sense, what Christ said is that “I know that I’ve been your teacher for three years. I’ve done many things, some of which you’re going to forget; but whatever else, please don’t forget this because what you are going to experience in the next twenty–four hours is the most important thing that I will ever do for you. Don’t ever forget it. You are remembering me.4

However, another dimension of anamnesis, presented in depth by 20th century Lutheran theologian Joachim Jeremias, roots Christ’s words of institution in the Old Testament parallels of memorial. Jeremias translated Christ’s words as “Do this that God may remember me.”5 Connecting the New Testament use of anamnesis to the LXX uses of the term, he argued that the memorials are “to insure God’s merciful remembrance.”6 Noticing the eschatological focus of Paul’s statement that the eucharist declares Christ’s death “until he comes,” Jeremias argued that the eucharist specifically is to remind God of Messiah so that he might bring about the kingdom in the parousia.7

This is perhaps too narrow. Certainly, the relation of the parousia to the Lord’s Supper is in the forefront of Paul’s mind when he binds past and future together when he says that in the Supper we “declare the Lord’s death until he comes,” but this eschatological dimension is not explicit in Luke 22. If Luke had wanted to imbue the words of anamnesis with a strictly eschatological flavor, surely he would have included Jesus’ declaration, “I will not drink again of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God” (Mark 14:25). The anticipated parousia, though the culmination of God’s faithfulness, is not his faithfulness in whole, and it seems to me that Jeremias’s narrow focus has allowed some to dismiss his suggestion more easily than they otherwise might have.

Jeremias’s thesis on the Godward character of the anamnesis has been controversial but has been adopted by some Reformed theologians. Michael Horton, for instance, echoes Jeremias when he says:

In our Western (Greek) intellectual heritage, “remembering” means “recollecting”: recalling to mind something that is no longer a present reality. Nothing could be further from a Jewish conception. For example, in the Jewish Passover liturgy, “remembering” means participating here and now in certain defining events in the past and also in the future. Together with their forebears, those who share in the Passover meal invoke the name of the suzerain for rescue: “I will lift up the cup of salvation and call on the name of the Lord” (Ps 116:13). And also, like the rainbow in the Noahic covenant, the Supper involves God’s remembering the oath that he made. The close bond between sign and signified in Passover is carried over into the New Testament celebration of the Lord’s Supper.8

While Jeremias has been the most influential recent proponent, this understanding of the Lord’s Supper as a Godward plea does not originate with him. Preceding Jeremias was Daniel Waterland who wrote A Review of the Doctrine of the Eucharist in 1773. In a discussion of anamnesis he says,

The service of the Eucharist (the most proper part of evangelical worship, and most solemn religious act of the Christian Church) must be understood to ascend up ‘for a memorial before God,’ in as strict a sense, at least, as Cornelius’s alms and prayer were said to do; or as the ‘prayers of the saints’ go up as sweet odours, mystical incense, before God. Whether there was any such allusion intended in the name ἀνάμνησις, when our Lord recommended the observance of the Eucharist as his memorial, cannot be certainly determined … but as to the thing, that such worship rightly performed has the force and value of any memorial elsewhere mentioned in Scripture (sacrificial or other) cannot be doubted….9

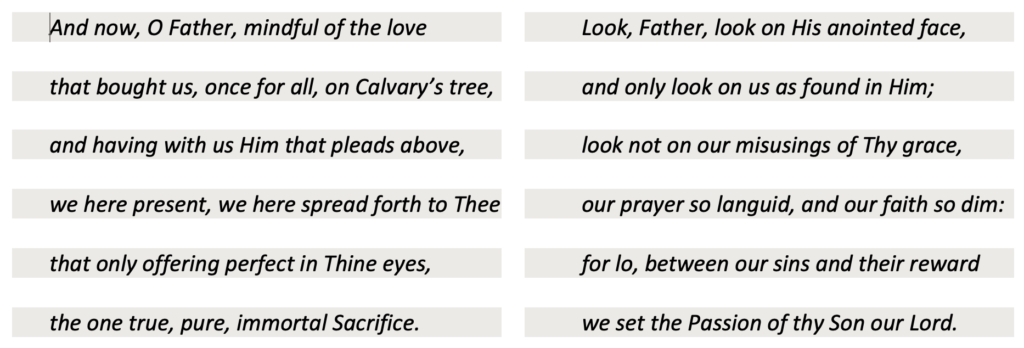

Waterman includes the notion of ascent in his conception of eucharistic memorial. The anamnesis is that which ascends to God’s presence like fragrant incense and reminds him to act in a way similar to all the prayers of the saints. This concept of Eucharist as God’s remembrance was expressed in the piety of the Anglican church in the eucharistic hymn, And Now, O Father, Mindful of the Love, by William Bright.10 The first two verses of the hymn read thus:

The hymn not only expresses a high view of the real presence of Christ in the Supper but also clarifies that the sacrifice is not a repeated one, but was accomplished “once for all, on Calvary’s tree.” Christ is locally situated “above” (i.e., in heaven), but the memorial token of his sacrifice is “spread forth” to God. In addition, the anamnesis has a soteric benefit. The Passion of Christ is set before God the Father as a reminder so that he might look upon and remember his Son rather than on our failings as sinful people.

Thus, without entirely discounting Jeremias’s eschatological dimension, we can see that Bright’s hymn expresses a broader meaning in the Supper. It is still Godward, but it is a plea that God might remember Christ, and that we might thereby have the immediate benefit of forgiveness and comfort.11

Witness of Early Eucharistic Practice

Is this understanding of the anamnesis in Christ’s words of institution innovative? Or can it be found in the doctrine of the ancient Church? While early church fathers did not typically formulate the meaning of anamnesis as explicitly Godward, the orientation of remembrance is sometimes ambiguous in their writings. Basil seems to speak of it in terms of recalling to the worshiper’s mind, when he says concerning the words of institution:

In what way are these words useful to us? They help us, when eating and drinking, always to remember Him who died for us and rose again….12

But often the orientation of remembrance is unclear, as in Chrysostom:

That we offer now also, which was then offered, which cannot be exhausted. This is done in remembrance of what was then done. For (saith He) “do this in remembrance of Me.” It is not another sacrifice, as the High Priest, but we offer always the same, or rather we perform a remembrance of a Sacrifice.13

Notice that the remembrance of Christ’s sacrifice is “performed.” We may well ask, who is the object of this performance?

Despite the ambiguity in the expository writings of the church fathers, the actual liturgical practice of the early church exhibits an unquestionably Godward orientation of anamnesis. Early eucharistic anaphoras are uniform in framing the recounting of Jesus’ acts of redemption, including the words of institution, as part of the prayer directed to God rather than in speeches directed to the congregation. A few examples will suffice to illustrate this.

In the anaphora of the Apostolic Tradition attributed to Hippolytus and the Egyptian anaphora bearing the name of Basil of Caesarea (as early as A.D. 357), for instance, both employ the words of institution in prayer addressed to God. The Latin Apostolic Tradition (4th c. translation of an earlier text) has:

Taking bread [and] giving thanks to you, he said: ‘Take, eat, this is my body that will be broken for you.’ Likewise also the cup, saying: ‘This is my blood that is shed for you. When you do this, you do my remembrance.’ Remembering therefore his death and resurrection, we offer to you the bread and cup….14

Similarly, the Egyptian anaphora of Basil:

Holy, holy, holy, you are indeed, Lord our God. You formed us and placed us in paradise of pleasure; and when we had transgressed your commandment through the deceit of the serpent … you did not cast us off for ever, but continually made promises to us through your holy prophets; and in these last days you manifest to us … your only–begotten Son, our Lord and God and Savior, Jesus Christ….

And he left us this great mystery of godliness: for when he was about to hand himself over to death for the life of the world, took bread, blessed, sanctified, broke, and gave it to his holy disciples and apostles, saying, “Take and eat from this, all of you; this is my body, which is given for you and for many for forgiveness of your sins. Do this for my remembrance.”

Likewise the cup after supper … “Take and drink from it, all of you; this is my blood … Do this for my remembrance. For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim my death until I come.”15

We may have even earlier evidence. In his Apology, which is the earliest known account of Christian worship, Justin Martyr speaks of the bread and wine as “food over which thanks have been given by a word of prayer which is from [Christ].”16 He then immediately recounts the words of institution, including Jesus’ command to “do this as my memorial.” This juxtaposition seems to equate the words of institution with the “word of prayer” from Jesus Christ himself, which is said over the bread and wine. The characterization of the words as a prayer certainly suggests a Godward orientation of anamnesis.

Indeed, in all the accounts we have of early liturgies, the words of institution, namely “Do this for the remembrance of me; this is my body…this is my blood” were universally employed as part of the eucharistic prayer directed to God.

The Godward direction of anamnesis as a general liturgical action is not limited to the words of institution. Some anaphoras, such as the liturgies of St James and St Mark, follow the words of institution with a litany of remembrances to God, interceding for various persons, each petition beginning with the words, “Remember, Lord” (Μνήσθητι, Κύριε).17

The pivot in emphasis from Godward remembrance to the cognitive recollection in the worshipper first occurs in Zwingli’s Action oder Brauch des Nachtmahls (1525) which redirects the words of institution to address the congregation rather than God,18 although in his earlier De Canone Missae Epicheiresis (1523) it is ambiguous whether the words of institution are part of the prayer or an exhortation to the congregation.19

In Luther’s Formula Missae (1523), he retained the words of institution as part of the prayer,20 but in the introduction of the Deutsche Messe (1526) Luther, too, has obscured the role of the institution in eucharistic service. The German liturgy does away with the full anaphora, spreading the remains of its various elements (e.g., Lord’s Prayer and Sanctus) over the actions between the end of the sermon and the distribution and interspersing the whole with exhortations to the congregation. Even the Lord’s Prayer has been paraphrased and is used as exhortation rather than a proper prayer, and this immediately precedes the words of institution.21 The effect is that it is unclear whether the anamnesis itself, even while intoned and called “Office and Consecration,” is intended to function as Godward prayer or as congregational exhortation. Certainly, the suggested removal of ad orientem celebration (i.e., the celebrant facing the altar) would give the eucharistic celebration, including words of institution, a more didactic emphasis.22

My intent is not necessarily to argue that our liturgical practice ought to revert to directing the words of institution themselves toward God in prayer. Luther, Zwingli, and the Reformers after them may well have been justified in reframing the words of institution as an exhortation. In doing so, however, they obscured the historic character of the anaphora’s anamnesis as Godward. Preserving the Godward orientation of anamnesis need not move the words of institution back into the prayer. After all, Jesus commanded not “say these words for my memorial,” but rather “do this for my memorial.” It is not one set of words or a particular phrase, but the whole act of eucharist, which constitutes anamnesis.

Finally, the words of institution are not the whole content of a historical prayer of anamnesis, though it is often the climax. The ancient anaphoras also present to God in prayer the church’s thanksgivings and a recounting of his work of creation and redemption, including Christ’s final sacrifice on the cross.

Egyptian Basil, after the words of institution, continues the prayer:

We therefore, remembering23 his holy sufferings, and his resurrection from the dead, and his ascension into heaven, and his session at the right of the Father, and his glorious and fearful coming to us (again), have set forth before you your own from your own gifts, this bread and this cup. And we, sinners and unworthy and wretched, pray you, our God, in adoration that in the good pleasure of your goodness your Holy Spirit may descend upon us and upon these gifts that have been set before you, and may sanctify them and make them holy of holies.24

Like the Psalmist who recounts to God his own deeds in the hearing of the assembly, petitioning him to act (Psalm 26), the church likewise rehearses God’s acts of power and mercy toward his covenant people. The accompanying petitions have a negative element, asking that God might not remember our sin for the sake of his promises in Jesus Christ and the memorial token of his once for all sacrifice, and as well as the positive that he might bless his people, also for the sake of our Lord who has invited us to feed upon him.

Conclusion

Remembrance is covenantal. There is a bidirectional character to the anamnesis of the Eucharist, just as there was a bidirectional character to the Old Covenant memorials. However, just as biblical covenants do not place God and humanity on equal footing, so also the two directions of remembrance are not equally ultimate. God is the first to remember in Scripture, in faithfulness to his own promises, when he remembers Noah in the flood and when he promises to remember whenever the sign of the bow he has placed in the heavens appears (Gen 8:1; 9:15–16).

God is always the first to remember his own promises. His remembrance of Noah in the ark precedes Noah’s offerings and the giving of the sign of the bow. God remembers the Hebrews in their captivity in Egypt even though they have forgotten YHWH (Exod 3:6–9; Ps 106:7). It is God who remembers when the prayers of Cornelius ascend as a memorial to heaven (Acts 10:4). Human remembrance is therefore secondary and imitative of God’s remembrance. The memorial feast days and meals, while bidirectional, express the same hierarchy of anamnesis. God remembers, and because he remembers, his people can also remember.

Although the primary emphasis in the hierarchy of direction in anamnesis is toward God who has given us the rite, it is also a remembrance by the congregation since it is the congregation who actually does the act of memorial in the eating and drinking of the Lord’s Supper.25 The Supper is God’s gift in Jesus Christ. It is the sign he ordained by which we might plead his promises to him. Anamnesis does not mean mental assent or mere intellectual recall. On the night of the Supper’s institution Jesus commanded his disciples to celebrate his memorial even though they could not possibly have mentally assented to remember his death, which had not yet occurred. Nor were they expected to understand what was about to happen, as in fact they did not until after the resurrection.

On the road to Emmaus, the resurrected Lord expounds to the two disciples how his own death was a fulfillment of God’s covenant promises in Moses and the prophets (Luke 24:13–15). His death was actually the result of God’s remembrance and acting upon his remembrance. God remembers, even when the two disciples on the road cannot remember. But their remembrance of Jesus is sparked when he takes bread, blesses, breaks it, and gives it to them. They remember after God remembers, and the sacrament itself is the instrument whereby God’s mighty acts in Jesus are brought to their cognizant intellect. In the same way, when we do the rite, the memorial is made. That is, we present to God the tokens by which he remembers Christ’s redemption for us, and God in turn brings him more and more to our memory through our breaking of bread.

This is the Godward character of anamnesis we find expressed in the piety and the liturgical practice of the early church.

NOTES

- The phrase is not recorded in either Matthew or Mark. ↩︎

- Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 36: Word and Sacrament II, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 41.

Also: “Christ also spoke with this phraseology: ‘Do this in remembrance of Me,’ that is, ‘Remember Me. Use the Word when you do this.’” Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 18: Minor Prophets I: Hosea–Malachi, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999), 171. ↩︎ - Institutes IV, xvii, 37. John Calvin and Henry Beveridge, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society, 1845), 442. ↩︎

- R. C. Sproul, What Is the Lord’s Supper?, First edition., The Crucial Questions Series (Orlando, FL: Reformation Trust, 2013), 18–19. ↩︎

- Joachim Jeremias, The Eucharistic Words of Jesus, trans. Norman Perrin (London; Philadelphia, PA: SCM Press; Trinity Press International, 1966), 251–252. ↩︎

- Jeremias, Words, 244. ↩︎

- Jeremias, Words, 252. ↩︎

- Michael Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 799. Emphasis his. Within this quote Horton cites Joachim Jeremias, Eucharistic Words. See also Matthew Colvin, The Lost Supper (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2019), 132. ↩︎

- Daniel Waterman, A Review of the Doctrine of the Eucharist, reprint. (London: Clarendon Press, 1896). Thanks to Pastor Jon Herr for bringing the work to my attention. For an in-depth biblical argument for anamnesis as reminder to God, see Max Thurian, The Eucharistic Memorial. Part 1 & 2 (John Knox Press, 1960–61). ↩︎

- First appearing in J. S. B. Hodges, Hymn Tunes: being further contributions to the hymnody of the church (New York: James Pott & Co., 1891), No. 67. ↩︎

- An earlier hymn by William Bright, Thou, who at thy first Eucharist didst pray (1881), includes the eschatological dimension: “So, Lord, at length when sacraments shall cease, may we be one with all thy Church above.” ↩︎

- E.g. Basil, On Faith 1.3. Basil of Caesarea, Saint Basil: Ascetical Works, trans. M. Monica Wagner, vol. 9 of The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1962), 388.

Also possibly Cyril of Alexandria, Ep. 86.5. “Therefore, let us commemorate and let us be mindful to offer what Jesus offered for us in the first month. For the Lord Jesus said, ‘As often as you will do these things, you shall do them in remembrance and memory of me.’ ” Cyril of Alexandria, Letters, 51–110, trans. John I. McEnerney, vol. 77 of The Fathers of the Church (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1987), 119. ↩︎ - Chrysos., Hom. Heb. 17.6. Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on the Gospel of St. John and Epistle to the Hebrews, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. T. Keble and Frederic Gardiner, vol. 14 of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post–Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1889), 449. ↩︎

- “You do my remembrance” is indicative rather than imperative in the Latin: meam commemorationem facitis. Paul F. Bradshaw, Maxwell E. Johnson and L. Edward Phillips, The Apostolic Tradition (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002), 40, 48. ↩︎

- R.C.D. Jasper and G.J. Cuming, Prayers of the Eucharist: Early and Reformed, Third Edition (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1990), 71. ↩︎

- διʼ εὐχῆς λόγου τοῦ παρʼ αὐτοῦ εὐχαριστηθεῖσαν τροφήν. Justin, 1 Apol. 66. Translation from Jasper and Cuming, Prayers of the Eucharist, 29. ↩︎

- C. E. Hammond, ed., Liturgies: Eastern and Western (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1878), 43–44, 184. ↩︎

- Bard Thompson, ed., Liturgies of the Western Church (New York: World Publishing, 1961), 154. The prayer proper concludes with the “Amen” immediately before the words of institution. ↩︎

- Jasper and Cuming, Prayers of the Eucharist, 186. The prayer proper has no distinct conclusion here, which makes the point of change to exhortation ambiguous. ↩︎

- Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 53: Liturgy and Hymns, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 27–28. ↩︎

- Luther, Works, Vol. 53, 78–81. ↩︎

- Luther, Works, Vol. 53, 69. ↩︎

- Byzantine Basil has “Remembering, therefore, Master …” (Μεμνημένοι οὖν, Δέσποτα). Hammond, Liturgies: Eastern and Western, 113. ↩︎

- Jasper and Cuming, Prayers of the Eucharist, 197. The Egyptian anaphora of Basil moves from anamnesis to epiclesis. It should be noted that while this anaphora does invoke the Spirit upon the gifts as well as upon the congregation, it petitions no transformation as later examples do, (e.g. The Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom). I have written elsewhere about the history and theology of epiclesis and what form it should (and should not) take in a Reformed conception of real presence. See my article, “The Epiclesis in Reformed Eucharistic Prayer” at https://theopolisinstitute.com/the-epiclesis-in-reformed-eucharistic-prayer/ ↩︎

- For this bidirectional character, see also Arthur A. Just Jr., Luke 9:51–24:53, Concordia Commentary (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1997), 832–833. ↩︎