In the Bible, all the world is a stage, but like the Tabernacle, that stage moves around a lot. David’s defeat of Goliath can only be fully understood as liturgy fulfilled in history.

Liturgy, as a sacrifice of praise, is the step-by-step process of resolving a conflict. It relinquishes all controversies against God, covers and expiates all the sins of men, reunites the Lord with His people, and allows Him to keep His promises to the faithful. The Law was established not to oppose the promises but to make a straight path for them. The drama of liturgy presents in symbol to the saints and to the world the resolution of all covenant history.

Popular takeaways from 1 Samuel 17 are that the bigger they are, the harder they fall, and also that it is impossible to win against a giant if you are playing by the giant’s rules. Less obvious, but more fascinating, is the fact that the details of the narrative ground this story in the long-running dichotomy between godless kingdom and godly priest-kingdom.

This rivalry between the offices of priest and king can be traced back to the early chapters of Genesis. Man is called to submit to heaven (covenant Oath: priesthood, the Tree of Life) that he might receive dominion on earth as a gift from God (covenant Sanctions: kingdom, the Tree of Judicial Wisdom). Only then is he qualified to speak for God (prophet). Instead, Man repeatedly steals kingdom and then claims the authority to speak as a god.

The priest-king obeys God and is blessed in all his endeavors. In contrast, the godless king steals God’s blessings but in his hand they transform into curses. His plunder sours into plagues. This scenario runs throughout the Bible to the book of Revelation, which employs allusions to every prior instance of the pattern to describe the strife between the fledgling priest-kingdom of Jesus and the self-exalting dynasty of the Herods, two sons wrestling in the womb of the new era like their fathers, Jacob and Esau.1

This ongoing conflict, which found its second expression in the world’s first brothers, Abel and Cain, is also the context of the exchanges between David and Goliath. The lamb-lion priest-king-in-training is a keeper of sheep like Moses, and the spear-wielding mighty man hunted men as though they were beasts, as did Nimrod and Esau.

A good drama will hook your interest by introducing the conflict very early in the piece. Like the Christian liturgy, the story of David and Goliath, in its first few lines, uses literary and architectural allusions to call upon all the import of the much greater drama of which this particular “day of the Lord” is only a fragment. The narrative begins with the armies of Israel and Philistia stationed upon two opposing hills, an obvious reference to Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim. From these twin heights, representative Israelites blessed the people and heard the curses of the covenant as the children of Abraham passed through into the Promised Land. But, as is always the case in the Scriptures, this is a reprisal with a twist. Goliath’s reference to slavery takes us back via the Exodus to the decrees of Noah concerning the future of the line of Ham’s son Canaan, who would be a servant to his brothers. The Philistines were not among the original Canaanite nations but sons of the Egyptians, descendants of Ham. This was a claim to a territory that God had given to the sons of Shem.

In Deuteronomy 27, the mountains themselves pictured blessed Abel and cursed Cain: the top of Ebal is a barren rock (the name means “bald stone”) overgrown with thistles; the slopes of Gerizim are watered by springs and cultivated with olive and fig trees. With this striking allusion in mind, the curses that David and Goliath hurl like fiery darts at each other before they engage in battle establish the significance of this gory episode as an important moment in God’s long-running holy war.

Likewise, through the canny lens of a practiced biblical (and systematic) typology, all of the other supposedly extraneous details that, in the minds of the modern reader, appear to slow down the narrative, are easily comprehended as important background information, and thus similarly crucial to our understanding of the event. These extra furnishings are included by the author to remind us that all of God’s work has the same “architectural” shape. Just as the Lord’s fiery chariot is described in Ezekiel 1 as a Tabernacle—a model, mobile extension of His court in heaven (possibly the cloud of glory that overshadowed Eden in Genesis 3 and Sinai in Exodus 24)—wherever His Spirit acts invisibly, God gathers whatever happens to be on hand and out of these earthly elements builds “unofficially” the same architectural configuration that governs every “official” sacred house.

These items upon which our God temporarily confers holy office in order to create and furnish another instance of His ubiquitous “theoscape” are also masterful allusions and cutting in-jokes, particulars written with the reader in mind who from childhood had been closely acquainted with the sacred writings (2 Timothy 3:15). They are instilled in us by the Spirit through literary repetition and repeated exposure to the text until recognizing them becomes instinctive. Like King Belshazzar in Daniel 5, too often the saint is surrounded by the gathered accouterments of the Sanctuary without being aware that their corporate witness invokes the presence of Yahweh.2 Under the New Covenant, it is the saints who are the vessels of God, which is why Jesus says that wherever two or more witnesses are gathered in His name, He Himself is present to pronounce judgment (Deuteronomy 19:15; Matthew 18:20). Wherever the temple of God is constructed on earth (forming), the breath of heaven will rush in like a mighty wind (filling) that Adam might stand upright before God.

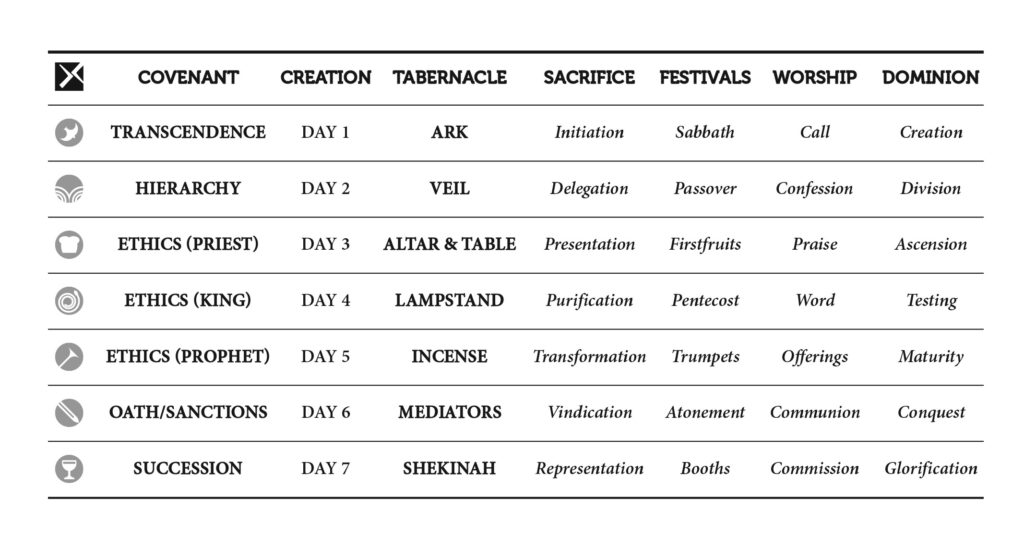

What we must understand is that the sequence that governs the composition of all biblical texts not only links the Creation of the cosmos with the elements of the Tabernacle but also with what went on within the Tabernacle. Liturgy itself is not holy war, but it is indeed a “heavenly haka,” a ceremonial war dance that prepares the warriors for battle.

THE TEXT AS LITURGY

The account of David and Goliath follows the heptamerous pattern of worship established in the Torah. The history has been recorded for us in “musical” form, and the reader is expected to be familiar with the tune. The practice of

trains the saints in the patterns and processes of heaven that they might go and measure them out upon the earth—and David did exactly that. He recognized that an idol had been set up in this improvised extension of the court of God, was offended by such a bald-faced rebellion in the face of God, and called upon the Lord to knock it down. As a man who could most likely recite the texts that explained what occurred behind the curtains of the Tabernacle, and who would have faithfully attended the feasts of Israel, David’s training in Word and Sacrament gave him the confidence to apply those patterns here as Government. Unlike Saul, and indeed, unlike Adam and Cain, the son of Jesse understood the link between the Garden and the Land, and between the Land and the nations of the World. Like the ark of Noah, the entire earth was represented in the Tabernacle of Moses. Since the anointing of David by Samuel followed the same pattern, the Tabernacle of Moses was now represented in the land by David, the future priest-king who would be permitted to eat—and thus to be—the sacrificial bread.3

So, like Belshazzar, Goliath defied God and suddenly found himself in Yahweh’s heavenly court, standing as a “serpent-king” exposed before the throne. God bowed the heavens to touch the earth that He might pronounce His judgment upon men. All He required to proceed was a second legal witness to “come down” (Priesthood: Genesis 11:7), “see” (Kingdom: Genesis 18:20-21; Ezekiel 8:6), and testify (Prophecy: Daniel 5:22-23). After corroborating His case against this human dragon with the evidence of a faithful Adam, thus bringing heaven and earth together as witnesses against the curse, He could carry out the rite of atonement.4 This explains why, as a unit, the narrative works through Israel’s annual festal calendar, culminating with David securing the nation’s future (Covenant Succession) by faithfully recapitulating the ministry of the High Priest on Yom Kippur, the Day of Coverings.

Creation: The nations are gathered together and a human serpent pronounces the curse

(1 Samuel 17:1-11)

(Day 1 – Ark – Initiation – Sabbath – Genesis: sacrifice chosen from the herd)

Division: David—Jesse’s lastborn—is sent to the battle with supplies for his brothers

(1 Samuel 17:12-18)

(Day 2 – Veil – Delegation – Passover – Exodus: sacrifice set apart and cut)

Ascension: David hears the curses of Goliath and the promised blessing upon the one who kills him

(1 Samuel 17:19-27)

(Day 3 – Altar & Table – Presentation – Firstfruits – Leviticus: sacrifice placed upon the altar)

Testing: Eliab—Jesse’s firstborn—disparages David, but David testifies of his successes as a shepherd before King Saul

(1 Samuel 17:28-37)

(Day 4 – Lampstand – Purification – Pentecost – Numbers: the holy fire descends)

Maturity: David is clothed for battle in priestly rather than kingly armor, and the combatants trade prophetic curses

(1 Samuel 17:38-47)

(Day 5 – Incense – Transformation – Trumpets – Deuteronomy: a testimony of fragrant smoke)

Conquest: David kills Goliath and cuts off his head with his own sword. The Philistines are scattered, slaughtered on the way to their cities, and their camp is plundered

(1 Samuel 17:48-54)

(Day 6 – Laver & Mediators – Vindication – Atonement – Joshua: God accepts the offering)

Glorification: Saul inquires of Abner concerning David’s pedigree and his Judahite heritage is discovered

(1 Samuel 17:55-58)

(Day 7 – Shekinah – Representation – Booths – Judges: the nation enjoys rest, reconciliation with God, and renewed rule in righteousness)

Mike Bull is a graphic designer in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney in Australia, and author, most recently, of Schema: A Journal of Systematic Typology, Vol. 2.

- For more discussion, see Everlasting Arms. ↩︎

- See also Nimrod in the Court of God. ↩︎

- See David the Tabernacle. ↩︎

- Abel and Cain were the “grandchildren” of the heavens and the earth, and their names allude to that fact. Cain worked the ground and Abel was a cloud or mist. Thus their roles in worship represented the testimony of heaven and the testimony of earth. This explains the Lord’s statement that Abel’s blood was crying from the ground as a legal witness against his brother. ↩︎