On the Woman Question

Strength and honor are her clothing

And she shall rejoice in time to come.

There’s been, I’m sorry to say, more Discourse. Primarily though not exclusively on Twitter. About the Woman Question, again. So I figured I’d make things a little worse by highlighting an aspect of a thing that I wrote a couple years back for The Calvinist International (may it rise again).

What do women want? This was Freud’s famous question; he asked it, which I’ve just found out, of Princess Marie Bonaparte, a great-grandniece of the emperor, a psychoanalyst in her own right, and – despite her title – not one of the dynastic branch of the family; she had had several affairs: with another of Freud’s disciples; with Aristide Briand while he was Prime Minister of France; and with her husband’s aide-de-camp, among others; whatever her answer to that question, one begins to suspect that she wasn’t getting it.

That’s just me being catty; sorry. The thing that women want that I want to focus on is that women want to be themselves.

And it’s hard to communicate this to the tribe of Men, sometimes. I’d tried to do so, a couple of years ago, in that old TCI piece, thusly (I paraphrase):

You run into lots of conservative and/or Evangelicalish Presbyterian guys who grew up quite a bit more fundamentalist, or at least nondenomenational/Baptistic. There’s a very common life experience that they share: extremely intelligent and driven, and also extremely pious, they found themselves, aged around 15-18, confronting a kind of horror so deep it might rightly be called existential.

The message they got from their churches was that the one worthy career was missionary or evangelist, and that any use of their time other than sharing the Gospel with their unsaved friends (if they had any) or with strangers (if they didn’t) was time wasted.

Furthermore, poetry is suspect, i.e. fiction. Also, the life of the mind is suspect. Getting passionate about anything that is not evangelism is suspect. Especially philosophy, because of Colossians 2:8.

These boys are in a horrible pickle: they are just coming into their own strength of mind and body and their own sense that there is a big world out there to explore, and fascinating ideas to look at, and they are told that this sense – which is itself their own response to the Creation mandate – is sinful.

They are also just coming to the age where true friendship can take root, the kinds of friendships that will create world-shaking political movements or engineering projects or artistic schools, friendships that will win the battle of the Glorious First of June, and they are told that they must look at these potential friends as objects of evangelism rather than as fellow-subjects, collaborators; they must look, precisely, at them rather than with them at something else, some common scheme.

This is horrifically destructive, to the boys and to the world.

There are a couple of typical paths out. One is to watch Chariots of Fire; obviously Eric Liddell was not a philosopher, but the sense of calling and correctness that he had in running, the sense of testing his own strength and making an impact in the wider world, parallels these boys’ own drive, their own vocation to philosophy.

The other is to read C.S. Lewis or Francis Schaeffer. Lewis is better because if you take the Schaeffer route you end up needing to eventually jettison Schaeffer’s own anxiety: he has, always, the tone of someone who comes from the same place those boys came from, the same suspicion that learning to play Beethoven’s Eroica needs to be justified; he thinks he has justified it, to himself and to his readers, but that belief is not natural to him. For Lewis it is natural: of course one would pursue a professorship of Medieval and Renaissance literature; why wouldn’t one? If Oxford doesn’t come up with the chair, so much the better for Cambridge.

It’s not that Lewis doesn’t address this directly, or that he doesn’t feel the challenge. He does address it, in “On Learning in Wartime,” and elsewhere; he does feel the challenge. It’s that he was not brought up to feel it: it comes to him as a matter of intellect rather than culture and upbringing, and could be answered more thoroughly by intellect.

Anyway, one way or another, these guys learn, with joy, that their own curiosity and ambition and drive to explore the physical and intellectual and artistic worlds, to freely and energetically follow whatever specialist or generalist callings God has placed on them, is not sinful, but is in fact obedient. Become who you are: they finally hear this and say yes.

The Discourse aspect of this is that what these guys need to know, which they do not always know, is that women have this experience too.

And (apparently) there are some churches that teach that they shouldn’t.

The way I would put it is this: to be told that you can’t have these ambitions or hungers because your only proper job is nurturing is just as bad as to be told that you can’t have these ambitions and hungers because your only proper job is evangelism.

So anyway, I’m thinking about this again in part because I’ve finally started reading Bronze Age Mindset.

(“Of course you are, because the Red Scare girls finally reviewed it,” said a friend last night; if you have no idea what I’m talking about I can only envy you; Dr. Leithart says I have to explain it; all I’ll say is that it’s fine if they have Clandestino and Dimes and that part of Chinatown, because we have KGB Bar and Bemelmans and Caffe Dante and large portions of the Upper West Side and the entirety of the Red Hook waterfront; go here for a briefing and here for some deep background, if you must; this is not about theology or ideology, it’s simply about control of territory on a relatively small island; BAP covers this extensively, as of course does Schmitt in Nomos of the Earth. The Metrograph is contested territory. We hope to have it secured by Christmas.)

What’s super interesting (to me) is that Bronze Age Pervert’s analysis of women and what I had understood to be Simone de Beauvoir’s are basically identical. Women are “mere life,” growth, biology, imminence. Kind of a swamp.

The thing that makes life transcendent, for both, is the male principle: differentiation, structure, real work as opposed to childbearing and rearing. Both have a deep distaste for the feminine and for the given, which they take to be the same thing, and both are basically existentialists.

I am told by another friend, who is a closer reader of de Beauvoir than I, that this is not fully accurate: de Beauvoir believes that women are perceived to be such, but that both men and women have aspects of the imminent and of the transcendent in them; that to be fully human, both must take the existentialist leap out of imminence, but that this is not a leap out of womanhood any more than it is out of manhood.

Of course de Beauvoir would have to argue this: there are, for her, precisely no “hoods,” no essences – not for men, and not for women either. But she can’t quite stick to this, it seems to me. Even verbally, no one, and especially no social commentator, can for more than a sentence or so keep up the existentialist/nominalist schtick.

De Beauvoir writes:

Man attains an authentically moral attitude when he renounces being in order to assume his existence; through this conversion he also renounces all possession, because possession is a way of searching for being; but the conversion by which he attains true wisdom is never finished, it has to be made ceaselessly, it demands constant effort. So much so that, unable to accomplish himself in solitude, man is ceaselessly in jeopardy in his relations with his peers: his life is a difficult enterprise whose success is never assured.

But he does not like difficulty; he is afraid of danger. He has contradictory aspirations to both life and rest, existence and being; he knows very well that “a restless spirit” is the ransom for his development, that his distance from the object is the ransom for his being present to himself; but he dreams of restfulness in restlessness and of an opaque plenitude that his consciousness would nevertheless still inhabit.

That embodied dream is, precisely, woman; she is the perfect intermediary between nature that is foreign to man and the peer who is too identical to him. She pits neither the hostile silence of nature nor the hard demand of a reciprocal recognition against him; by a unique privilege she is a consciousness, yet it seems possible to possess her in the flesh. Thanks to her, there is a way to escape the inexorable dialectic of the master and the slave that springs from the reciprocity of freedoms.

My more-careful-de-Beauvoir-reading friend paraphrases this as “you want women to be unconscious nature so that you don’t have to contend with them as equal. but you also hate nature because you want to be free from the horror of being born. sucks to be you.”

Well, yes, I see this: and the funny thing is that without the negative-coded language she could be Nietzsche himself, here. My MCDBR friend says de B is not agreeing that this is eternally so, but that it is the pickle into which too-essentialist post-nineteenth century men have put themselves. She can understand the existentialist pushback:

“De Beauvoir thinks (and I think too!) that we all want being and existing, but there’s so much rhetoric involved, particularly in 19th c. French literature, that’s like, ‘be happy, woman! you’re Nature!’ which personally would annoy me. If someone told me I was the embodiment of something else and not me, like piled dozens of bad novels on my head about this, I would go berserk.”

The thing is, we do want both “being” and “existing,” in de Beauvoir’s terms – we want rest and adventure at once, receiving a gift and imposing our wills—the home in port and the open sea – but everyone wants this, men and women. It’s answered in the New Jerusalem. And it’s not just that there is no harm if men see, in women, an ikon of the New Jerusalem, who is, after all, the Bride. There would, I think, be a harm if they did not see this in us. But as they do, they must remember that she also is searching. She also wants to exist, as well as to be.

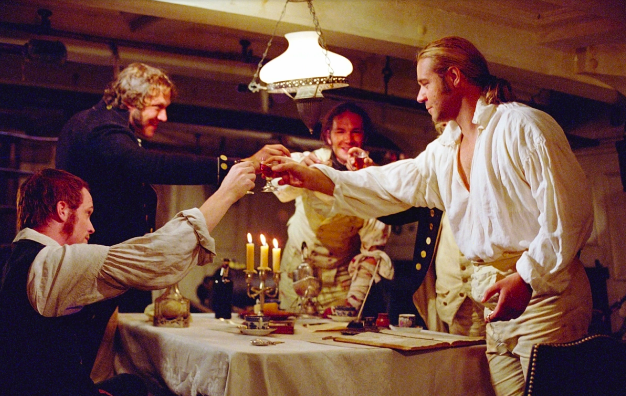

It’s interesting to realize that where we are now is precisely in the church militant: in that aspect of her that is pictured as a ship, the Barque of Peter, the Ark. Stories about ships, my husband has noticed – we watched Master and Commander together early on – are stories about worlds that are both adventuring and enclosed: a ship like the Surprise is a home, a world, but it is a world on an adventure. This quality of being a world, a home, which is itself on an adventure, is… I’m not sure what it is. It’s something important.

What would our scriptures say to BAP’s typology? Eve is the mother of all living; there is that Jungian sense of fecundity; but she’s also the highest refinement of human being, the one whose existence throws the differentiation of the sexes into relief; Adam knows himself as different from the animals by naming them, a task of culture and differentiation, but above all by recognizing and naming her.

Her existence proves that existence does not precede essence, which is if you think about it kind of funny. She is a living repudiation of existentialism. The Second Sex indeed. Own it, sisters.

Typologically, there are then two kinds of women (and of course in every woman there is a struggle between these two): the strange woman who breaks down barriers and does not respect her own, and the wise woman whose very body is, until the right time, a hortus conclusus.

That wise woman is Wisdom herself, who builds her house with seven pillars, who draws the lines that enclose space in that way, who is paganized as grey-eyed Athena but who always was better than Athena.

If you as a man see in women only chaos, only Tiamat, that means that you have been listening not to her but to the woman Folly. You have been learning from her, and what you have learned is disorder, senselessness.

“Stolen water is sweet

food eaten in secret is delicious!”

But little do they know that the dead are there,

that her guests are deep in the realm of the dead.

Having learned that from her, you believe that the fault is in Woman. It is not. It is in you.

And women ourselves – what are we to do? Well, we’re going to have to be existentialist essentialists, I suppose: We have to choose, in virtue, to become the woman Wisdom: to become who we are, rather than to fail to become her, and instead become the woman Folly. (For the Patrick O’Brian fans, the ones who read the books as well as watching the film, I will delicately point out here that this is not, for each woman, a choice between being Sophie Williams and Diana Villiers.)

I am enough of an Anglo-Catholic to suspect at least that we have a particular ally in this: the one who has the name which contains the word for the primal sea, the womb of all life – yam–, but who is a specific person, a woman in history, one drop of that sea –mar.

That was Eusebius’ derivation of her name; Jerome translated this into Latin as stilla maris; at some point a copyist made one of those possibly-guided-by-providence goofs and transcribed this as Stella Maris, and one of Mary’s most ancient titles, is thus Star of the Sea. (It is a serendipity that the Latin for Sea is Mare.)

Women can and should nurture children; this is, yes, one of the things we are for; nearly all of us feel this. This is good and beautiful, and when we do this, we are in some sense embodying an archetype, and that too is good. If, in fear of being swamped by your own nature, you reject that nature, you are hurting yourself, stunting yourself. But my de Beauvoir close reader friend puts it like this: “It’s hard to defeat this move when it asks you to embody a good quality; it’s just that no one is a quality.”

This is tricky! We are not nominalists and we don’t want to be! But we also are not, ourselves, the Forms.

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

We can sometimes have, along with Gerard Manley Hopkins, a little Scotus, as a treat.

To refuse to become a nominalist, to know and love the fact that we have natures and are, in those natures, caught up into the heart of the world to such an intense degree that Christianity and paganism can seem to overlap; but also to know ourselves as reasoning individuals, uniquely called, and to refuse to squash ourselves or each other into immanentist-essentialist boxes: it’s a tough needle to thread! But that’s what we’re here for, gang.

To clarify, because one must do this, in the Discourse: none of this means that women ought to be priests. I don’t think they should, or – really – can be; a man is the matter for ordination, as water is the matter for baptism. Nor does it mean that we should seek the difference between men and women only in the prescriptive commands of scripture: in a thin complementarianism of arbitrary prohibition and instruction, as though God were a voluntarist: that would indeed be tyranny, and God is no tyrant. There is nothing arbitrary in Christ’s choice of twelve men as his apostles, any more than there is anything arbitrary in his choice of that other Mary to be the one who bore the news, first, to them. There is nothing arbitrary in anything: that’s the point.

But it does mean that in discussing any of these things, men had better know what they are dealing with, and one of the things that they are dealing with is the ravenous desire, the good desire, to know and make and learn and build, to exist, to become, which God placed in their sisters as he placed it in them.

“The true man wants two things: danger and play. For that reason he wants woman, as the most dangerous plaything.”

I suppose there may be some women who, while being true, do not themselves want danger and play.

I’ve never met one.

Susannah Black received her BA from Amherst College and her MA from Boston University. She is an editor at Mere Orthodoxy, Plough Quarterly, The Davenant Institute’s journal Ad Fontes, and Fare Forward. Previously, she was associate editor at Providence. She’s a founding editor of Solidarity Hall and is on the boards of the Distributist Review, The Davenant Institute, and The Simone Weil Center. Her writing has appeared in First Things, The Distributist Review, Solidarity Hall, Providence, Amherst Magazine, Front Porch Republic, Ethika Politika, The Human Life Review, The American Conservative, Mere Orthodoxy, Fare Forward, and elsewhere. She blogs at Radio Free Thulcandra and tweets at @suzania. A native Manhattanite, she is now living in Queens.

This article originally appeared at Mere Orthodoxy.