Many years ago, while perusing Janice Anderson’s revised doctoral dissertation, Matthew’s Narrative Web: Over, and Over, and Over again, I was impressed by her attention to literary structures of repetition within and across Matthew’s Gospel.1 Her research, in part, nudged me closer toward my present conviction that Matthew carefully crafted his entire gospel as a chiasm.2 One section that caught my attention long ago and has stuck with me ever since is, as she says, the “most striking repetition” contained in Matthew 4:23 and 9:35, which contains twenty words in common.3 Surely, this large cluster of repeated words was no mere coincidence on Matthew’s part. Anderson even observes that a “number of scholars have argued that this repetition has a structural significance.”4 In what follows I posit that this repetition has more than mere structural significance; it also underlines the importance of Jesus’s ministry having and maintaining a distinct quality and character of its authority.

Anderson describes in detail how Matthew weaves together larger themes and structures across his Gospel, and how repetitions like 4:23 and 9:35 form a “strong undercurrent which runs beneath the surface.”5 Regarding this undercurrent, Anderson writes:

These verses form an inclusio around Jesus’ teaching (chs. 5–7) and healing (chs. 8–9) activities. The Sermon on the Mount and the miracles of chs. 8–9 are concrete examples—individual scenes—illustrating two of the activities summarized in 4.23 and 9.35.6

By concentrating repetition in these two passages (4:23 and 9:35), Matthew is drawing attention to a pattern early on in the Gospel. Matthew has woven themes of teaching, healing, and the calling of his disciples into an observational pattern for understanding Jesus’s public ministry. This pattern also applies to the leadership Jesus commissions and the authority he gives them after his resurrection (Matt. 28:16–20).

To see this pattern unfold, let’s look at Matthew 9:35 and the verses that follow, ending at 10:4 and right before the second discourse (Matt. 10:5–42) of Matthew’s Gospel begins.7 I have underlined the important structural points of repetition below:

And Jesus went throughout all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore, pray earnestly to the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.” And he called to him his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to heal every disease and every affliction. The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother; Philip and Bartholomew; Thomas and Matthew the tax collector; James the son of Alphaeus, and Thaddaeus; Simon the Zealot, and Judas Iscariot, who betrayed him.8 (Matt. 9:35–10:4)

Pay attention to the pattern that emerges from this pericope9: Jesus teaches the gospel of the kingdom, and heals, and afterward he calls his twelve disciples to join him in this work. In this instance teaching and healing precedes calling. This clustered mention of teaching, healing, and calling isn’t isolated to chapter nine, though. As Anderson pointed out above, these striking words in chapter nine are repeated immediately prior to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, the first discourse within Matthew’s Gospel (chs. 5–7):

While walking by the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon (who is called Peter) and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea, for they were fishermen. And he said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.” Immediately they left their nets and followed him. And going on from there he saw two other brothers, James the son of Zebedee and John his brother, in the boat with Zebedee their father, mending their nets, and he called them. Immediately they left the boat and their father and followed him. And he went throughout all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction among the people. So his fame spread throughout all Syria, and they brought him all the sick, those afflicted with various diseases and pains, those oppressed by demons, epileptics, and paralytics, and he healed them. And great crowds followed him from Galilee and the Decapolis, and from Jerusalem and Judea, and from beyond the Jordan. (Matt. 4:18–25)

Before we go any further, notice carefully that this pericope is incredibly similar to Matt. 9:35–10:4. Also, notice that the order of teaching, healing, and calling within is slightly different in this earlier scene. In 4:18–25, Jesus first calls disciples, then he teaches and heals. As we will see shortly, this reversal in the order of repetition between chapters 4 and 9 is deliberate, framing Jesus and his apostles’ ministry with purpose.

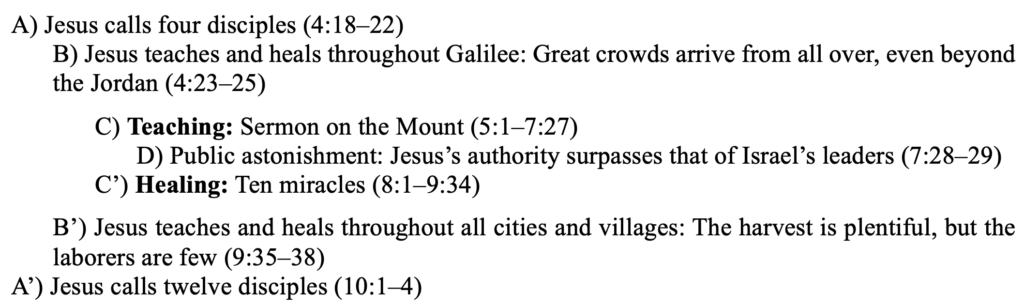

Bridging these two pericopes, which form an obvious inclusio,10 are two major sections: the Sermon on the Mount (chapters 5–7), where Jesus teaches, and a series of ten miracles (chapters 8–9), where he heals. As Anderson noted earlier, these two sections (one lengthy teaching discourse and one lengthy narrative section of healing) are concrete examples that illustrate the two activities (teaching and healing) summarized in 4:23 and 9:35. And as we unpack this structuring pattern, the literary intentionality of Matthew becomes increasingly evident:

Notice carefully that between Jesus’s Sermon and the narrative section about healing, we find an expression of public astonishment (section “D”). Not only does this structure of teaching and healing anchor Christ’s ministry within Matthew’s early chapters, but at its heart there lies a striking claim about its quality and character: “The crowds were astonished at his teaching, for he was teaching them as one who had authority, and not as their scribes” (7:28–29). This publicly acknowledged authority not only reveals who Jesus is but also highlights the need he came to address. Far from a mere display of power, Jesus’s authority responds to a culture in crisis, as Matthew sets the stage by portraying Israel as longing for a leader to guide them out of disorder and despair.11

This longing becomes especially clear before Jesus appoints the twelve apostles, when Matthew describes Israel as “harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd” (9:36).12 Their spiritual and cultural authorities, the scribes and Pharisees, have failed them, and God’s people need authority that actually heals. Matthew’s portrayal of Jesus as an authority who “heals” is unique. When compared with other synoptic Gospels, Matthew has “a distinct preference for the verb ‘to heal’”13 which frequently occurs in contexts that contrast Jesus’s authority with the established authorities of Jerusalem and its temple.14

Early in Jesus’s ministry, he calls these leaders of Israel “vipers” (3:7; cf. 12:34; 23:33), and in the Sermon on the Mount, he warns of their hypocrisy. He critiques those within the synagogues and Sanhedrin who judge unjustly while craving praise (6:2, 5, 16; 7:5), labeling them “wolves in sheep’s clothing” (7:15; cf. 10:16) and unhealthy trees bearing rotten fruit (7:17–20). Such leaders, though cunning,15 burden and mislead God’s flock like reckless shepherds, inconsiderate of the consequences of their teachings (5:20–6:18; cf. 23:1–31). In stark contrast, Jesus steps forward as the shepherd Israel desperately needs.

This image of sheep without a shepherd vividly recalls Israel’s historical struggles. In Numbers 27:17, Moses prayed that his people whom he guided through the wilderness would not be abandoned like “sheep without a shepherd”16 and exposed to the perils and disorder of their environment. Centuries later during Jesus’s ministry, Israel faces a comparable crisis, burdened underneath Roman rule and weakened by religious corruption. Without Jesus as their chief Shepherd, one can imagine them languishing in the lost, lordless condition Moses feared.

Through this lens, chapters 4–10 of Matthew’s Gospel unfold as a grand replay of Israel’s exodus story with Jesus embodying roles akin to both Moses and Joshua. Consider the parallels:17 Moses appointed leaders (Exod. 18) before proclaiming God’s Law at Sinai (Exod. 19); likewise, Jesus calls disciples (Matt. 4:18–22) before ascending a mountain to teach with unparalleled authority (Matt. 5–7). After Sinai, Israel departed with a vast cloud following (Numbers 10:11–13); after his teaching, Jesus descends with a great crowd of witnesses trailing him (Matt. 8:1). In chapters 8 and 9, Jesus performs ten remarkable miracles, starting with healing a leper (Matt. 8:2–4), a sharp contrast to Israel’s ten wilderness rebellions (Num. 14:22), which began with Miriam’s leprosy (Num. 12:1–16).

Following Moses, God appointed Joshua to lead, sending (ἀποστέλλω) scouts into surrounding lands (Josh. 2:1).18 Jesus too embodies a Joshua-like role, guiding Israel toward rest, not through physical conquest but by appointing apostles (ἀπόστολοι, Matt. 10:2) and dispatching (ἀποστέλλω, Matt. 10:5) them to confront spiritual and cultural adversaries: the serpentine scribes and wolfish Pharisees preying on God’s flock. Through these actions, Jesus emerges as the shepherd Israel longed for, blending authority and compassion in a way that surpasses even Moses and Joshua.19

The carefully crafted structures, themes, types, and motifs across Matthew’s Gospel invite us to marvel at this astonishing Shepherd, whose authority astounds the crowds (7:28–29) and whose compassion inspires faith (9:33–36). Yet, Jesus is more than the best Shepherd—he is the Shepherd of shepherds, never leading alone. By the Sea of Galilee, he called four fishermen—Simon Peter, Andrew, James, and John—to abandon their nets and follow him (4:18–22). Later, facing a plentiful harvest, he gathered twelve apostles, entrusting them with his power to heal and proclaim the gospel of his kingdom to the lost sheep of Israel (10:1–4). In this, Matthew’s Gospel offers hope: The Father sent his Son into the world as the Chief Shepherd,20 who in turn sends out under-shepherds to care for their flocks as he does.21

This call extends beyond the twelve, reaching every generation through Jesus’s greatest calling (28:16–20). Part of what makes the “Great Commission” so great is that Jesus continues summoning overseers for his flock, guiding us through our own wilderness wanderings with the same help and healing presence that marked his apostles’ ministry. He has not abandoned us. In troubled and helpless times, the Church bears witness to the kingdom God draws near and to his Son’s authority over all.

______________________________________________________________________________

Jonathan E. Sedlak is a graduate of the Theopolis Institute. He is an independent scholar based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the author of Reading Matthew, Trusting Jesus: Christian Tradition and First-Century Fulfillment within Matthew 24-25.

NOTES

- Janice Capel Anderson, Matthew’s Narrative Web: Over, and Over, and Over again, JSNTSup 91 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), 150. ↩︎

- Anderson, Matthew’s Narrative Web, p. 138, engages with the structure proposed by C.H. Lohr, which was used by Peter F. Ellis in Matthew: His Mind and Message (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1974). Ellis’s illustration of Matthew’s chiastic framework is highlighted in my book, Reading Matthew, Trusting Jesus: Christian Tradition and First-Century Fulfillment within Matthew 24-25 (Theopolis Books, 2024), 52. ↩︎

- Anderson, Matthew’s Narrative Web, 150. ↩︎

- Anderson, Matthew’s Narrative Web, 150. ↩︎

- Anderson, Matthew’s Narrative Web, 19. ↩︎

- Anderson, Matthew’s Narrative Web, 150. ↩︎

- For an explanation of what I mean by the “second discourse” of Matthew’s Gospel, see my post on the Theopolis Blog,Reading Matthew, Identifying Discourses: A Closer Look at the “Six-Discourse” Proposal. ↩︎

- Unless noted otherwise, all scripture citations are from the ESV. ↩︎

- A pericope is a short, self-contained section of text that forms a coherent unit. ↩︎

- An inclusio is a literary device where a story begins and ends with similar themes, phrases, ideas, etc., thereby creating a frame that brackets the content between. ↩︎

- Ian Boxall, Discovering Matthew: Content, Interpretation, Reception, Discovering Biblical Texts (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2015), 114, suggests that this order presents Jesus’s ministry in microcosm. By following the first major discourse (chs. 5-7) with a clear expression of public astonishment about his authority, followed by a neatly packed narrative section of healings, Jesus’s early-life activity points toward the creation of a “community of disciples… whom he will lead”. ↩︎

- The Greek text of Matt. 9:36 is ὡσεὶ πρόβατα μὴ ἔχοντα ποιμένα (“like sheep lacking a shepherd”). ↩︎

- Boxall, Discovering Matthew, 107. Boxall also notes that there are 16 occurrences this verb “to heal” in Matthew, as opposed to merely five total throughout Mark. ↩︎

- According to Boxall, Discovering Matthew, 107, the placement of this verb “to heal” across Matthew’s Gospel is intriguing. For example, in contrast with Mark’s Gospel where Jesus commissions twelve apostles but does not mention healing, Matthew’s version says that the apostles are specifically commissioned to “heal” (10:1, 8). This theme develops as Matthew’s Gospel progresses, too. When Jesus in interrogated by authorities about curing the man with a withered hand, Mark’s Gospel frames all concerns around what is lawful on the Sabbath to be about doing good or doing harm (Mk. 3:4), whereas Matthew frames all concerns around healing on the Sabbath (Matt. 12:10). For more on this, see Boxall, Discovering Matthew, 106-110. ↩︎

- There are numerous illustrations of Israel’s authorities as being cunning, and perhaps too numerous to list here. A few examples should suffice. In Matt. 9:3 the teachers of the law inwardly accuse Jesus of blasphemy after he forgives a paralyzed man’s sins, showing accusatory intent without direct confrontation. In Matt. 9:11 the Pharisees question Jesus’s disciples about his choice of company, implying superiority and seeking to undermine him. In Matt. 9:34 the Pharisees slyly attribute Jesus’s exorcisms to demonic power. In Matt. 12:2 and 14 the Pharisees accuse Jesus’s disciples of unlawful sabbath activity, and in a clear act of cunning they deliberately seek grounds to charge Jesus by questioning him about healing on the Sabbath. ↩︎

- The Greek text of Numbers 27:27 LXX (Septuagint) is ὡσεὶ πρόβατα οἷς οὐκ ἔστιν ποιμήν (“like sheep for which there is no shepherd”). ↩︎

- For these and other parallels across Matthew’s Gospel, see Peter J. Leithart, The Gospel of Matthew Through New Eyes (Volumes 1 & 2): Jesus as Israel (Athanasius Press, 2018-2019). For a condensed list of parallels, see Jonathan E. Sedlak, Reading Matthew, Trusting Jesus, 42-56, 411-21. ↩︎

- The LXX has Joshua “sending” (ἀποστέλλω, pronounced “apostellō”) scouts into the land. The verb ἀποστέλλω is cognate with the noun ἀπόστολος (pronounced “apostolos”), from which we get the English word “apostle.” ↩︎

- Although the typology of this section in Matthew focuses heavily upon Exodus motifs with Jesus as a Moses and/or Joshua figure, the theme of a shepherd whom Israel longs for extends from this Exodus period and continues into the later prophets as well. Boxall, Discovering Matthew, 109, notices some connections between the Messianic Shepherd in Matthew and the Servant-healer of Isaiah 53. Also, the Messianic-Shepherd motifs in Jeremiah 2:8; 3:15; 10:21; 25:34-38 and Ezekiel 34:23-24 are particularly noteworthy among the larger prophets, and I am grateful to Jacob Collins for pointing these out to me. ↩︎

- I Peter 5:2-4. ↩︎

- Matt. 18:12; John 10:3-4. ↩︎