This essay is adapted from my articles in Theopolis’s In Medias Res as a series of Holy Week meditations.

Like many celebrities such as Kanye or Beyoncé or Adele, Josquin des Prez (d. 1521) was often known only by his first name, in his own time as now. “Josquin” is all you need to say to make some music lovers swoon with delight. Although he’s not the household name of the likes of Bach or Handel, he has always been considered, by those who have drunk deep from his music, to be incomparable amongst composers of sacred music.

Yet you may be forgiven, in listening to some of his music, if you wonder what the fuss is about. There are some people for whom Josquin’s music is like a bolt from the blue, and others for whom it might be something of a disappointment after the hype his fans (such as myself) make of it.

Take De profundis for five voices, a setting of Psalm 130 (or Psalm 129, as Josquin would have known it). It is one of the traditional penitential psalms originally instituted by St. Benedict for liturgical use in Holy Week. It begins:

Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, O LORD. Lord, hear my voice: let thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications.

First of all, it’s important to note what Josquin’s music is not doing. It is not dramatic. It does not build to some climax. It is not interested in “text painting,” in having the music portray what is going on in the text at a given moment, like the furious sounds of Verdi’s Dies irae. The notes of the music are not telling a story like a Sonata form. These sorts of things were of no interest to Josquin or his contemporaries.

Exactly how, then, is Josquin’s music interacting with “Out of the depths, I cry unto thee, O Lord?” One answer is simply that the music doesn’t have to interact with the text; the music is singing the text. After all, this is vocal music: what are the notes but continuations of the vowels? No more intimate connection could already exist than a singer singing the text of the Psalm.

There might be one exception where something dramatic does happen in the music. David Fallows notes in his biography Josquin that De profundis “create[s] a canvas rather than a narrative,” all except for the final cadence of the piece, its last chord, “which comes as though out of nowhere.”1 I find this is often the case for Josquin motets: the endings are seemingly rude and abrupt. He is seldom dramatic and he does not create musical narratives. His whole approach is different. What is that approach?

The answer may lie in another work which goes by different names: Nimphes, nappes/Circumdederunt or Christus est mortuus or Haec dicit Dominus. It has these different names because Josquin’s work was so popular during the 16th century. Sometimes publishers of his music would just simply add texts that they liked better and entirely cut out Josquin’s original lyrics. Martin Luther loved the motet and played it often in his home; he knew it as Haec dicit Dominus.

As indicated by the slash (/), there are two texts simultaneously in the music: the Circumdederunt part comes from Psalm 116:3: “The sorrows of death compassed me, and the pains of hell gat hold upon me: I found trouble and sorrow.” Oddly, the other part, Nimphes, nappes comes from a secular song: “Water nymphs, Nereids, Dryads, / come and mourn my desolation / for I suffer such affliction / that my spirits are more dead than alive.” Such pairings weren’t uncommon in this period and were usually allegorical readings of secular poetry of one sort or another. Presumably we might see Christ in Gethsemane as the person suffering “such affliction that my spirits are more dead than alive.”

Josquin’s approach to composing this sort of music is called counterpoint. Rather than a melody with chords, it is multiple melodies, each balancing its concerns with the other so that the whole sounds harmonious. This is a hard thing to do without the wheels coming off the machine; humans just singing together, each on their own melody, don’t sound nice by accident. There is a complex set of rules which governs the behavior of these multiple melodies that composers must observe. Counterpoint is the musical embodiment of 1 Corinthians 11, “Tarry for one another.” It is an artful balance of players deferring to one another.

For Medieval composers, these rules weren’t just human constructs. They were rooted in the way God made the universe: an octave was a ratio of 2:1, a fifth 3:2, a fourth 4:3, and so on. Music was beautiful because it reflected God ordering the universe through number. Their music, as they saw it, was a humble submission to the created order by prioritizing the beauty and hierarchy of these sorts of intervals.

Josquin’s music does this and it does it beautifully. But the miracle of Josquin is that, almost as if by accident, the music cannot help being deeply human and emotional. His obedience to these laws of counterpoint seem to melt into the background. Martin Luther, speaking of this very piece, famously said that Josquin “is the master of the notes and makes them do what he wants whereas other composers must allow the notes to do what they want.” Musicologist Rob Wegman has shown how this is Luther’s doctrine of law and grace at work: Luther is saying that Josquin is not bound by counterpoint as if by law, but rather Josquin’s is a counterpoint of grace.2 It is effortless, motivated out of love rather than drudgery. Josquin is not a slave to this contrapuntal order but an heir.

Although Josquin doesn’t tend to use the music to portray the text, there are notable exceptions. Musicologist Michael Long speculated that Josquin’s mass cycle Missa Di dadi as a whole was about two things, neither of which are mentioned explicitly in its text: gambling and Christ’s crucifixion.3 And you may already be able to guess where Long was going—crucifixion and gambling, at least, are related: “They part my garments among them, and cast lots upon my vesture” (Psalm 22:18; cf. Matt. 27:35; Mark 15:24; Luke 23:34; John 19:24). Christ’s clothing is gambled away at the foot of the cross.

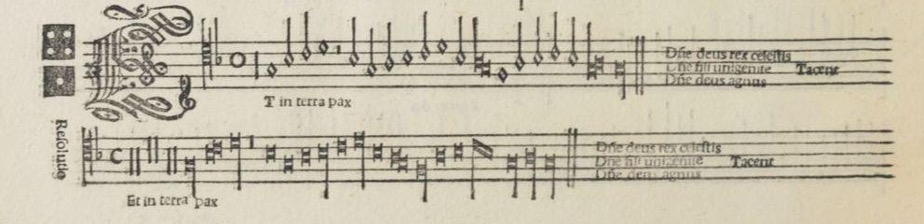

As Josquin has written this particular mass cycle, each movement’s tenor part is in essence a riddle: the tenor will not fit with the other parts unless it multiplies its rhythmic values by the ratio on the face of the dice. His musical printer, Ottaviano Petrucci, was careful to print the dice face alongside the tenor part (see below). In other words, for every one whole note that a soprano might sing, the tenor would sing two whole notes if the other face shows two, or four whole notes if the other face shows four, as in this picture from the “Et in terra pax”:

Why is gambling showing up in this mass? Michael Long argues (pretty convincingly) that the game of dice should be understood to be between the human soul and Christ. The connective tissue is the musical tune the tenor actually employs, which was a popular love song. “Will you never realize,” says the love song, “That I am yours and will so remain?” The game of dice abruptly comes to an end in the Sanctus, the movement that contained the liturgy during which the Host was elevated and the Eucharist consecrated. Christ rolls the winning dice. We sinners may have cast lots for his clothing, but he was playing for our souls. The final movement of the mass, the Agnus dei, does not have these dice faces. Christ has won.

“It was a strange and dreadful strife,” says Martin Luther in Christ lag in Todesbanden, “when death and life contended.” Luther here is drawing on a long tradition of portraying Christ’s death and resurrection as a battle. In particular, that idea fired the imaginations of composers in the fifteenth century in their L’homme armé masses.

Just about every composer did it, if they were worth their salt: a polyphonic choral mass based on a popular tune about “the Armed Man” who terrifies his enemies with an iron coat of mail. The practice started in Burgundy and northern France in the 1460s—it may have had something to do with Duke Charles the Bold’s desire for a new crusade—but the practice eventually spread even to Italy and the Sistine chapel choir.

Who is “the Armed Man?” Music historians have puzzled over it for decades. But recently, some consensus has emerged about the primary meaning of the symbolism. The illuminations in the manuscripts make it clear, like this knight in Josquin’s Missa L’homme armé (see below). He is stabbing a dragon made into the shape of a capital A (the whole word is “Agnus”). The armed man is killing a dragon. The armed man, as musicologist Craig Wright demonstrates in The Maze and the Warrior, is first and foremost Christ.4

In the middle of the Agnus Dei from Josquin’s own L’homme armé, three voices break off from the group and sing the second invocation (“Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world”) alone. Josquin gives only a single melody line of music, with the cryptic instruction “Trinitas.” By deciphering some of his notation, singers would be able to create a three-part canon from his music where they’d sing the music at different rates of speed. The beginning of the melody they sing is not one Josquin himself originally came up with; he borrows it from a man who was likely his friend and mentor, Johannes Ockeghem, who wrote a secular love song Ma bouche rit.

In singing this music, the musicians are picturing the economy of the Trinity into which Christ’s resurrection ushers us. In the words of the fifteenth-century music theorist Johannes Tinctoris, “Music makes the church militant become like the church triumphant.”5

I have chosen a recording of Josquin’s L’homme armé super voces musicales by a group called Cut Circle. I like the way they sing the Agnus Dei. Too many choral ensembles deprive Josquin’s music of its pulsing blood and vocal grain, especially in the Agnus Dei. Cut Circle’s director Jesse Rodin understands that the Agnus Dei is a liturgical climax, that the peace granted to us in its final words (“dona nobis pacem”) is a full-throated, glorious peace. Cut Circle’s recording also gives us the great joy in Josquin’s music, even in moments when the key might strike moderns as “minor” and “sad.” This glorious conclusion to the Armed Man mass is anything but sad—it is a victory song after a strange and dreadful strife.

Yet again we see Josquin appropriating secular themes for a religious context: gambling, secular love songs, and now even pagan themes (Christ came from “starry Olympus”). Of course, it’s hard not to see this as irreverent; the secular, in entering the sacred sphere, is thereby defiling it. The direction, however, is likely the opposite. When Christ touches the woman with an unclean flow, it is she that is cleansed, not he that is defiled; no less, says Athanasius was “the all-holy Word of God…defiled by being known in the body; on the contrary, being incorruptible, He quickened and cleansed the body also.”6 Josquin’s music seems constantly aware of this new economy, inaugurated first in the incarnation and later in the resurrection—no secular referent is safe from being absorbed into Christ. Even the sordid, adulterous courtly love or the demonic Olympic pantheon is not safe from the power of Christ: his story robs the symbols of their original referents and takes them effortlessly to himself.

John Ahern has a PhD in musicology from Princeton University. His dissertation was a survey of the sacred music of the fifteenth-century French composer Fremin le Caron. He has been a church organist, pianist, and choir director at several churches and within several denominations, and he is now worshipping and playing music in the PCA. He currently teaches Latin and humanities at The Wilberforce School in New Jersey. Together with Medora, his wife, he enjoys the antics of his brood of children whose number is ever increasing such that, were it specified here, this biography would almost certainly be out of date by the time it is read.

NOTES

- David Fallows, Josquin (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009), 343. ↩︎

- Rob Wegman, “Luther’s Gospel of Music,” in Michael Klaper, ed., Luther im Kontext: Reformbestrebungen und Musik in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts, Studien und Materialien zur Musikwissenschaft, 95 (Hildesheim, Zürich, and New York: Olms, 2016), 175–200. Available here. ↩︎

- Michael Long, “Symbol and Ritual in Josquin’s ‘Missa Di Dadi’,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 42 (1989), 1–22. ↩︎

- Craig Wright, The Maze and the Warrior: Symbols in Architecture, Theology, and Music (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001). ↩︎

- Johannes Tinctoris, Complexus effectuum musices. See Gilles Charlier and Johannes Tinctoris, On the Dignity and Effects of Music: Two Fifteenth-Century Treatises, tr. Reinhard Strohm, Institute of Advanced Musical Studies (London: King’s College London, 1996). ↩︎

- Athanasius, On the Incarnation 17, tr. Archibald Robertson, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. 4, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (1892). ↩︎