This is the first of two essays aiming to introduce the reader to Pascal’s Wager. The second will address criticisms of the Wager.

In the early 1990s, a perennially popular British pop star was interviewed on British television about his very public evangelical Christian faith. “What if,” the reporter asked him, “it turns out you are wrong—that you are mistaken about Christianity and so have lived and wasted your life for something fraudulent and untrue?”1 The singer, after assuring the reporter of his confidence in Christ and Christianity, then doubled back on the reporter: “Let’s say I am wrong,” he said. “What have I in fact lost? I have gained a joyful, fulfilled life. I have been prompted by my faith to treat others better than I would have otherwise. I have been part of a community of believers that are the truest of friends.” And if proved right, he said, “I have gained eternal life with my savior.” The performer asserted that his choice was more rational than that of the nonbeliever: “If I had chosen not to believe I would have given up that joy and risked eternal life, losing everything. You tell me: how am I in any way worse off believing as I do?” The reporter quickly shifted to another line of questioning, appearing not quite sure how to answer.

Knowingly or not, the pop singer was presenting to the reporter Pascal’s Wager (and the reporter had probably not learned about Pascal’s Wager, else he might have been able to reply). This was a contemporary version of Pascal, who similarly said, “I should be much more afraid of being mistaken and then finding out that Christianity is true than of being mistaken in believing it not to be true.”2

This apologetic argument bears the name of 17th-century French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, as it comes from Pascal’s Pensées (“thoughts”). These were a series of notes, or fragments, that were apparently going to be compiled into a volume on Christian apologetics. Although there are several hundred such fragments, four (387, 418, 816, and 917) are usually associated with Pascal’s Wager.3 The Wager, although usually thought of as an apologetic argument in favor of the existence of God, was in fact offered by Pascal as something less (or more) than that. He saw this line of reasoning as pertaining not to God in the abstract or any generic God, but instead related to the specific Christian God. He also did not believe it “proved” God, but instead invited those already curious and open to considering the possibility of Christian faith to take the first steps, convinced that once within the Christian fold the power of Christ and the compelling case for Christianity proper would overcome the obstacles remaining. These disclaimers notwithstanding, Pascal’s Wager has been subject to considerable criticism, by Christians and non-Christians alike.

This essay will give an overview of Pascal’s argument, along with its strengths and strictures. A follow-on essay will consider recurrent criticisms of the wager and suggest at the end how Pascal’s Wager can be productively used by the Christian for the right persons in the right circumstances.

The very name given Pascal’s Wager suggests at once that it is not an attempt to prove the existence of God. If the end result of a poker hand could be proven in every instance, a bet would not be gambling in any sense of the word: it would be a certainty, not a wager. So, too, with Pascal’s Wager: it assumes that the existence or nonexistence of God cannot be proven conclusively by reason:

“Either God is or he is not.” But to which view shall we be inclined? Reason cannot decide this question. Infinite chaos separates us. At the far end of this infinite distance is a coin being spun which will come down heads or tails. How will you wager? Reason cannot make you choose either, reason cannot prove either wrong.4

This is a critical point, often missed by critics of Pascal. He is not claiming to prove God: he is arguing for how one prudently should respond given that by reason it is impossible to prove the existence or non-existence of God.5 (At the same time, we know Pascal highly regarded the traditional arguments in favor of God’s existence. Even if these were dispositive to the Christian, however, Pascal recognized that to the nonbeliever struggling with the claims of Christianity another approach would be necessary that appealed to logic but did not claim to prove the Christian God’s existence.)

A second presumption of the wager is that it is not optional or negotiable: one cannot simply choose not to play. We must play because we live. When we claim not to decide, that, too, is a wager of sorts. The person in a casino who chooses not to gamble is at some level betting that his or her funds are likely to have a better return in the wallet than on the tables. In Pascal’s Wager, deciding not to decide is deciding not to believe, choosing at least for the moment that life without belief is more advantageous than a life of belief. (“Whoever is not with me is against me,” Jesus said; Matt 12:30, NRSV). And while this decision not to decide may be changed, at some point death will force the bet to be made and resolved with finality. There is no option not to wager, and eventually for everyone there is no opportunity to change one’s bet. Death does not facilitate avoidance of the wager: it seals one’s wager forever.

The Wager, then, is rightly termed prudential, as it suggests what the ubiquitous “reasonable man” or “prudent person” should do when confronted with this decision. It may seem like it is a 50-50 proposition, with disbelief and belief equally likely (since by reason one presumably cannot prove either the existence or non-existence of the Christian God). It would thus seem like the coin toss at the beginning of a game: indeed, Pascal had even referred to the decision in just such a way, as we have seen. And coin tosses are equal-odds propositions. If this were the case it would make as much sense not to believe as to believe, and to the extent the costs and benefits were equal, there could be no compelling argument for belief.

But Pascal’s language of coin toss did not capture his entire argument. As in everyday matters of life, decisions take into account the odds of something happening, the potential costs, the potential rewards, and the “transaction costs” (the costs of playing). Even if the odds are exactly the same, the other variables will drive and commend a prudent course of action. And if the odds are smaller for a particular course of action, the other variables can nonetheless make prudent what may on its face appear to be extremely unlikely. For Pascal, the case for Christianity was a strong one. The nonbeliever may perceive the case as far weaker than does Pascal. But the potential infinite positive benefits of the Christian life (and potentially eternal negative consequences for failing to believe) settle the matter in favor of Christian belief, vitiating any unfavorable odds. Pascal puts it this way:

But here there is an infinity of infinitely happy life to be won, one chance of winning against a finite number of chances of losing, and what you are staking is finite. That leaves no choice; wherever there is infinity, and where there are not infinite chances of losing against that of winning, there is no room for hesitation, you must give everything. And thus, since you are obliged to play, you must be renouncing reason if you hoard your life rather than risk it for an infinite gain . . . .6

So in mathematician Pascal’s formulation reason may not prove the existence of God, but reason dictates that we seek him, and failing to do so reflects the renunciation of reason.

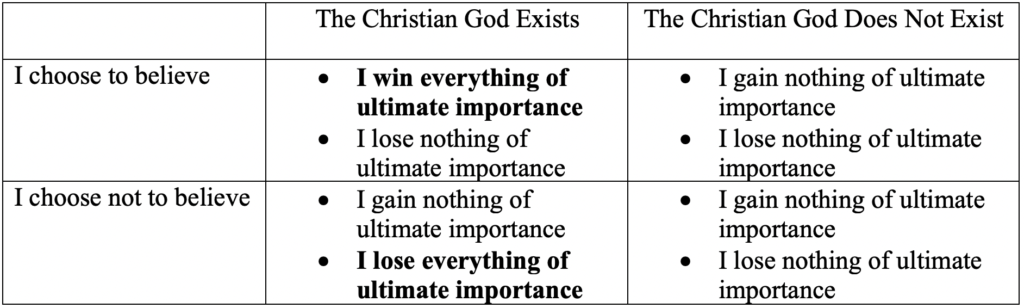

The possibilities and payoffs thus line up like this:

In brief, if the Christian is proven wrong, nothing of ultimate importance is lost. But if the nonbeliever is proven wrong, the nonbeliever loses everything. And though Pascal did not speak of eternal damnation as that ultimate loss, that is the stark implication of Scripture.

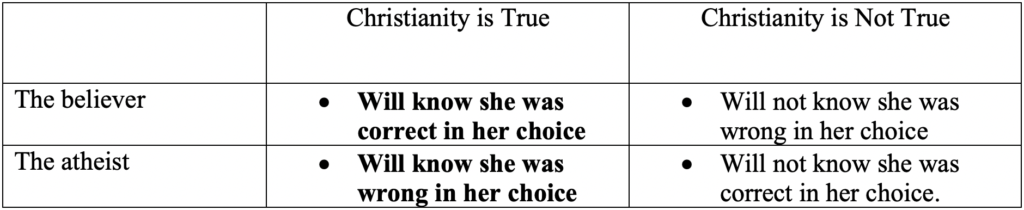

Another implication of Pascal’s Wager pertains to whether the person making the wager will ever know she has “won” or not—i.e., will know whether she chose wisely. Because for the atheist there is nothing beyond this life, here is how this plays out:

So while the Christian will know if she is correct, and reap the benefits of knowing this, the nonbeliever will never know she is correct (and if she could, one has to ask, where would be the satisfaction anyway?) She is thus without hope of ever having full knowledge—unless that knowledge is something too terrible ever to contemplate or desire. In Pascal’s Wager, only the Christian is both promised full assurance and protected from the knowledge of having erred. There is only one reasonable way ever to know the truth, and that is to believe. As Thomas Morris puts it: “we can say that for atheism there is a final no-satisfaction guarantee, whereas for theism there is a final no-dissatisfaction guarantee.”7

This is Pascal’s Wager in brief. But the Wager is not without its detractors from within and without Christian circles. The most potent criticisms of the Wager—and how even with its limitations it can remain powerful–will be explored in a second essay, “Is the Betting Rigged in Pascal’s Wager?”

Alexander Whitaker is the President of King University in Bristol, TN.

- I recall this interview with (now Sir) Cliff Richard from my time living in Britain from 1991 through 1995, but have been unable to locate a transcript. This recounting is my paraphrase (from memory) of the noteworthy exchange. ↩︎

- Peter Kreeft and Blaise Pascal, Christianity for Modern Pagans : Pascal’s Pensées Edited, Outlined, and Explained (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993), 292. (Fragment 387) ↩︎

- This paper for consistency uses the term “Pascal’s Wager,” but some writers refer to it as “Pascal’s Bet,” or “Pascal’s Gambit.” Several other of the Pensées are sometimes used to discuss the Wager, but these seem to be the standard ones. ↩︎

- Kreeft and Pascal, Christianity for Modern Pagans, 293. (Fragment 418) ↩︎

- Daniel Fouke, “Pascal and the Wager,” ed. Robert Audi, Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 563. ↩︎

- Ibid., 294 (Fragment 418). ↩︎

- Thomas V Morris, Making Sense of It All: Pascal and the Meaning of Life (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1992), 121. ↩︎